America has a ghetto, not a housing problem | Peter Banks

Urbanism requires order.

Intro

It was a hot summer day in 2020 as I pulled off I-90 and began to work my way towards Hyde Park. Anticipation, fear, and anxiety all mixed with painful pleasure in that moment as the air conditioner in my family’s 2006 Honda Pilot struggled to keep the oppressively damp Illinois heat at bay.

Only two months earlier I had graduated from George Mason and my move to Chicago in order to work at Booth as a research assistant represented the culmination of nearly a decade of slowly and painfully crawling my way up the Ivory Tower. Looking back now the main thing I remember from that day, however, is the visage of looted stores and shattered glass as the tires hummed down E53rd street.

Chicago had been wracked by racial conflict since George Floyd’s murder and Hyde Park, an island of affluence in a sea of poverty, had been no exception. To my naive suburban eyes it wasn’t only the damage that came as a shock, but also the pattern of which stores had been touched and which ones left unmolested.

On nearly every pane of unbroken glass stood a sign of some sort proudly proclaiming the establishment’s “blacked owned business” status — one of the only exceptions to this rule was a liquor store which had been looted, and where the torn shreds of a poster pathetically begging the thieves to “please leave the store alone” remained fluttering in the wind.

This experience of arriving in Chicago during the “Summer of Floyd” was the first part of an answer to a question that had been plaguing me ever since I began to first look for apartments earlier that year. “Why is rent so much cheaper in the South Side?” My studio apartment barely cost $600 a month, for example, but few people seemed keen to move on this ‘opportunity’.

Instead the opposite appeared to be true — nearly everyone who could afford to crammed themselves into a small corner of the city stretching roughly from the Loop to Evanston, where they paid comparably astronomical rents. This is to say nothing of the hundreds of thousands of people who lived far out in the suburbs and drove or rode the train for over an hour each way, all for the privilege of paying twice what they would have in Bronzeville. Why? Well, as I would discover over the next two years, there were hidden costs to living in the South Side, costs that more than compensated for any financial savings from paying less in rent.

That time would forever change the way I thought about housing in America and would cement a simple belief:

America, in more ways than one, has a ghetto not a housing problem.

There is housing available in large quantities for affordable prices in almost every major American urban core but most people choose not to live in it for rational reasons. When you dig into the actual logic residents give for why they oppose development across this country, again, and again, the main reason they offer is fear that new or proposed construction will attract crime and other anti-social behavior. This desire of locals to preserve their community has led to a decline in the “elasticity” of supply across this country, meaning that due to supply constraints, the most in-demand areas ironically build the least — and they have as a result the most exorbitant prices.

It doesn’t stop there, though. The ghetto crisis in this country is doubly pernicious because, not only does it lead to a housing affordability crisis by forcing everyone into an arms race to escape violence and disorder, but the mere existence of these blighted urban areas also represents an enormous policy failure on the part of our government – one that seriously calls the competency of the entire postwar regime into question.

Due to our persistent failure to maintain rule of law in major population centers, more and more citizens have been turning to radical conclusions about the world to explain the facts on the ground. Among suburban — often, but not always, White — Americans, for example, it encourages racial stereotypes about Blacks. And in the ghettos themselves it leads many to the belief that the state doesn’t care about their lives or future.

In much of this country the state does not maintain a monopoly on violence, and it is clear that the policies we have been pursuing do not actually address the root causes of this issue. It was indeed the incredible injustice of American urban poverty which lay behind the emotional demands of the BLM movement, even if their policy suggestions were, in my opinion, very ill-advised.

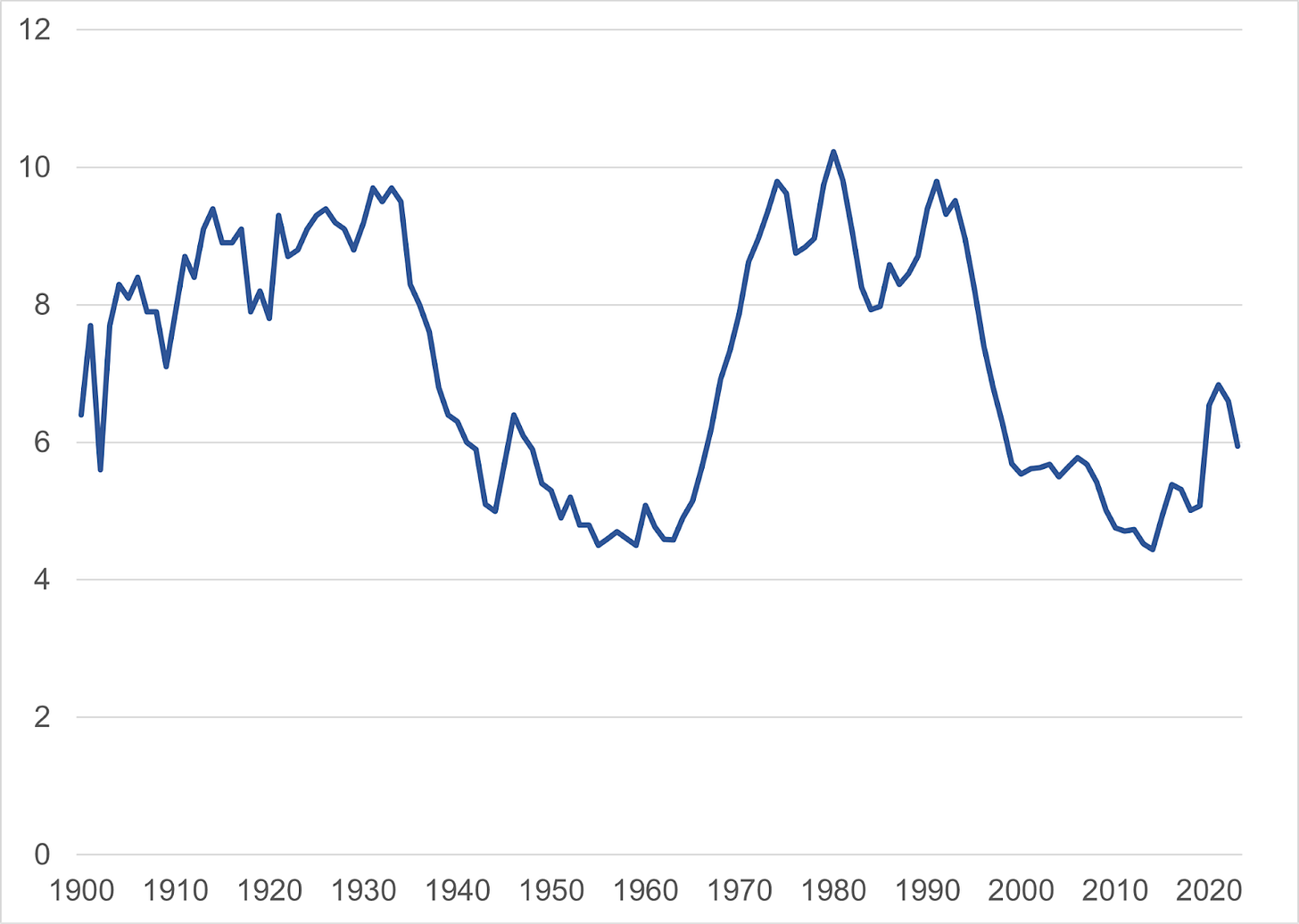

The picture is not one of only doom and gloom, though. A pattern of poverty and violence is not inevitable and cities have managed to transform themselves before. New York City stands as an incredible example of what this can look like. Since 1990 the city has managed to lower its murder rate from a high of 31 murders per 100,000 people to 5 per 100,000 in 2023.

It accomplished this transformation through a no-nonsense, tough on crime approach, and the result yielded a city that continues to attract hundreds of thousands of newcomers per year.

Internationally, cases like El Salvador show with extreme-enough policies that crime can be almost totally eliminated. It is vitally important that people who wish to see liberalism thrive show that they can make places like St. Louis — where the murder rate is over 50 per 100,000 — safe without stooping to the levels of a leader like Bukele or Trump (with his recent deployment of the national guard to American cities), because the Human and social costs of tolerating dens of intense crime are astronomical.

By improving our cities we can do much to reduce housing costs while also reviving dead engines of American growth and killing at the root a major source of radicalism in this country. But in order to accomplish this task, policy makers need to have more clarity about the deep roots of poverty and appreciate that academic research has shown that the best way to reduce crime is to punish it.

The rest of this article will be structured as follows: first, I will outline the true scope of American urban dysfunction; second, I will discuss how this distorts the housing market; third, I will address some counter arguments and outline what I believe should be done; and finally, I will conclude with reflections on my personal experiences in Chicago.

American Urban Dysfunction

The origins of America’s Ghetto problem in 2025 lie in the middle of the 20th century.

Between 1960 and 1992 America went from less than 9,000 murders a year to a peak of 24,000. Other crimes such as burglary underwent a similar process and increased by a factor of nearly 5. A disproportionate share of this growth occurred in the old industrial cities of the Northeast and Midwest, which were also entering a period of economic decline during that era, the result of a weakening US industrial base.

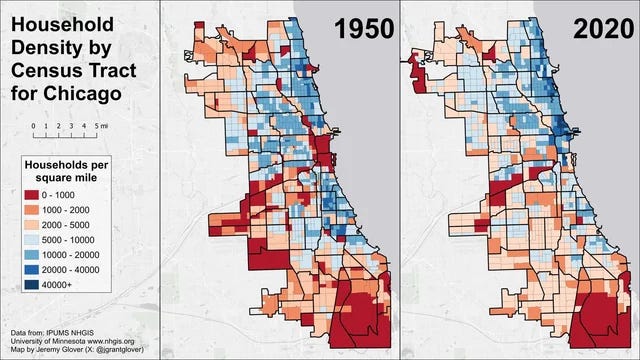

Because of this dual shock of massively elevated crime and a weakening of the industrial sector, many of these cities entered into what can only be characterized as a death spiral. St. Louis, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh each also lost roughly half their populations, and even cities like Chicago (which managed to weather the storm relatively well) shed nearly a third of their residents.

No city however suffered more than Detroit, which, between 1950 and 2020, lost almost 70% of its residents. In 2012, about one-third of its land — 40 square miles — lay vacant, with tens of thousands of abandoned homes and factories, and in some neighborhoods the vacancy rate exceeded 30% compared to a 1.6% national average.

In other words, what I observed in Chicago was not unique to that city. The problem of concentrated areas of low socioeconomic status marked by extreme levels of crime is reflected in city after city across this country. Although this pattern can be difficult to discuss because it overlaps with the very culturally-sensitive topic of race, it is still an undeniable fact and something policy makers must grapple with.

How Crime Distorts Housing

One of the primary reasons it is necessary to handle this problem directly is because of the way street-level chaos distorts the housing market.

The principle effect is the functional removal of urban cores from most people’s social lives. If you compare the pattern of Human geography in the US vs Europe, the hollowing of our cities is immediately obvious. 79 percent of the population in the United States’ 50 largest metropolitan areas lived in the suburbs and between 2000 and 2015, and those same suburbs accounted for 91 percent of the population growth and 84 percent of the household growth. By contrast, in many European cities, the vast majority of people live in dense, mixed-use central districts or built-up zones (rather than low-density, car-dependent suburbs).

As a result, the average US city with a population over 500,000 has a density of less than a quarter the relative rate in Europe.

What is driving this pattern is not a lack of demand among Americans to live in cities — as evidenced by the astronomically high rents in the neighborhoods which are safe — but instead fear.

Part of this fear comes from parental concerns about existent cohort effects on childhood outcomes (Chetty et al. 2016; Chetty et al. 2022), but most of it has to do directly with crime. Academic research looking at population flows paints a clear picture: people move away from chaos (Liska & Bellair 1995; Cullen & Levitt 1999). This out-migration, combined with evidence that crime seizes up the housing market (Dentler & Rossi 2024), puts increasing downward pressure on these neighborhoods, leading to the deathspirals that we observe.

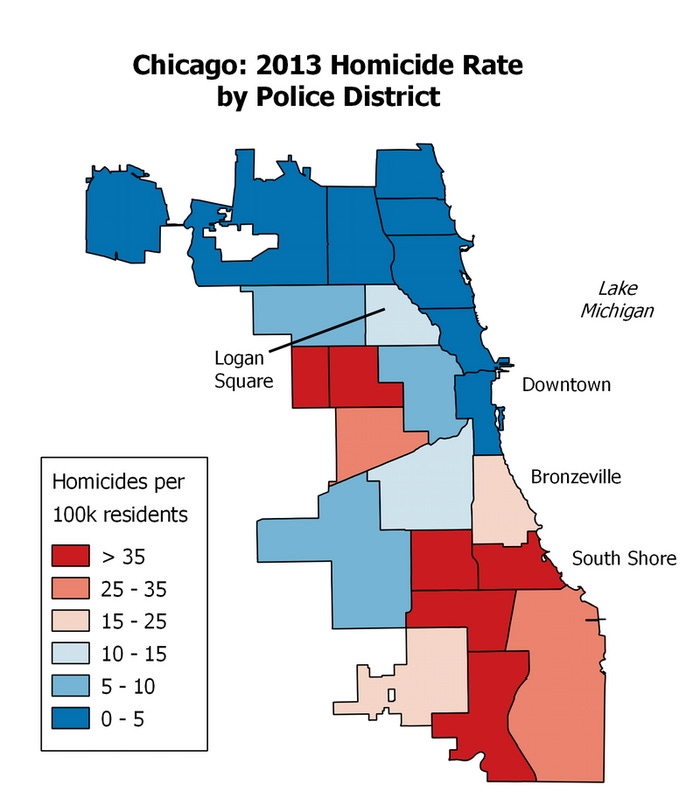

Within the same city, the relationship at the district-level between collapsing population density and crime victimization is evident for anyone who is willing to look. Focusing on just Chicago, the highest crime police precincts have murder rates that are 7-8 times as high as the safest ones.

And it is, predictably, these same neighborhoods that experienced a collapse in population density.

Since the only mechanism Americans have to insulate themselves against disorder is price discrimination, the result has been enormous pressure at the local level to stifle all new construction. Few people are willing to openly admit this publicly. But behind closed doors, concerns about affordable housing inviting the “wrong type of people” are regularly voiced.

Even high income housing can be seen as possibly dangerous to housing values because of a process academics refer to as “filtering,” whereby high income households will select into newer, premium units, opening up their old housing for poorer residents to then occupy. Economists often identify the hyperlocal desire to preserve prices as a major impediment for why communities oppose new construction (Glaeser & Gyourko 2025), but it isn’t always obvious how new construction would reduce the price of a single family home unless this influx was accompanied by income or crime shocks.

Tragically, given the enormous evidence for gains to people moving to affluent areas (Chetty et al. 2016) and a lack of evidence that new construction (even low income construction) leads to increased crime (Albright et al. 2016; Diamond & McQuade 2017), the near total shutdown of new building has almost certainly done more harm than good. However, the concerns of residents cannot be easily brushed aside — and if we want to break this negative cycle then clearly something must be done to solve the core problem.

Policing and Punishment Work

So what should we do? I mentioned at the start of this article that NYC is an example of a city that has largely turned itself around. Understanding how it pulled this off is important to figuring out how other cities can similarly improve. The short answer is that they crushed crime by punishing it. But before I dive into the academic research behind this claim, it is worth understanding just how insane NYC was in the middle of the 20th century.

On October 12th, 1977, as Game 2 of the world series was underway, ABC cameras covering the game caught on video part of an inferno raging in the city, leading to the famous anachronistic quote: “Ladies and gentlemen, the Bronx is burning.”

Over the previous couple of years, the neighborhood had been overrun with arson attacks resulting in a loss of 40% of housing units; in some census tracts more than 97% of buildings were burned down. It wasn’t the only event. That same year, early in July after a lighting stick hit a substation on the Hudson River, most of the city lost power and the closest event our nation has ever experienced to The Purge unfolded. Hundreds of people were injured, billions of dollars in damages from looting occurred, and for a brief moment all semblances of civilized society were stripped away.

It is no surprise then that between 1950 and 1980 NYC lost more than 900,000 residents. It appeared to be on track for a similar collapse to what was undergoing in other cities. However, they managed to turn the decline around and since 1990, the population has surged by more than 1.2m.

This was accomplished by taking a tough-on-crime approach towards disorder. In a 2004 article, Steven Levitt outlined four variables that had led to the collapse, identifying the following: 1) An increase in the number of police; 2) a rise in the prison population; 3) the receding crack epidemic; and 4) abortion. Notably, he found that the strong 1990s economy, changing demographics, and better policing strategies did not explain the decline. This is in alignment with Corman and Mocan 2002, which had found that increased misdemeanor arrests explained between 33 and 86 percent of the observed decline in robbery and car theft.

In other words, in order to turn our ghettos around, cities should adopt NYC’s 1990s policies and ramp up both arrests and punishments. It is time for us to get hard on crime again. More specifically, cities should target repeat offenders who are often arrested an absurd number of times only to be rereleased back onto the streets. Iryna Zarutska’s killer, for example, had been arrested 14 times already before murdering her in cold blood.

In addition to arresting repeat offenders and keeping them away from the public, cities should be willing to open their pocketbooks and fork out more for police personnel, and the federal government should help those places that are willing to act.

Finally, cities need to be able to communicate to families that these policies are credible and that politicians are more interested in protecting the rights of the law-abiding over criminals. What is required is moral courage — the willingness to assert that civilization requires order, and order requires the enforcement of norms.

One of the most common pushbacks someone will receive when they talk about the need for more policing is that since the intense criminality in our ghettos is the result of poverty, we should address that directly, rather than increase enforcement.

It is probably true that if we could abolish poverty in this country we would make great strides towards addressing crime. But the alternative policies offered by people who would prefer this angle are lackluster, and the effects where it has been introduced have been catastrophic.

Disentangling precise causality around the 2020 crime surge is complex, but the body of research showing that tough policing reduces crime is frankly enormous (Levitt 1997; Levitt 1998; Di Tella & Schargrodsky 2004; Klick & Tabarrok 2005; Mello 2019; and Braga et al. 2024), and analysis focusing specifically on the depolicing that occurred in Denver in 2020 found a clear link with the crime spike, particularly as it related to homicides (Nix et al. 2024). Scott Alexander also has a very good article where he arrives at a similar conclusion.

Zooming out of the academic research and back to reality for a second, it is worth reiterating that America is already an extremely wealthy country and even the poorest quintile, according to CBO’s 2024 report, earns over $45,000 a year after accounting for transfers and taxes, This is well above the global average and above many wealthy, developed countries. Our problem is one of an unwillingness to enforce the rule of law, and one of a deep culture of violence in this country, accelerated by the prevalence of guns, not material poverty.

If we can turn cities like Detroit, St. Louis, Baltimore, and countless others back into dense urban areas like they once were, we would relieve pressure on “superstar cities” like NYC while also saving the lives of, literally, thousands of our citizens. The problem is not that we need to make new urban areas, but that the ones which exist have been destroyed by decades of incompetence and negligence. This can be reversed, and NYC shows the path.

My time in Chicago

Thus far, this article has been primarily focused on statistical and academic evidence around the American Ghetto problem. But I think my own experience in Chicago and eventual “flight” to Palo Alto is also informative. I will conclude the article with some reflections on my time there.

As I mentioned at the outset, between 2020 and 2022 I lived in the South Side of Chicago. First in Hyde Park itself, and then in the summer of 2021, my (now) wife and I moved to an apartment just to the north of E51st street in a neighborhood called “Bronzeville”.

Starting with Hyde Park — it is one of the most unique neighborhoods in the US. Although it is a part of the city of Chicago and Cook County, most day to day policing is done by the University of Chicago police who aggressively patrols the streets. The relative safety that this creates has meant the neighborhood is extremely racially diverse (for the South Side) and has a thriving restaurant and commercial business district.

But it is not immune from the surrounding chaos, as was evidenced that summer in 2020 when I saw the smashed windows and looted stores. Nor is it clear of its own local problems. For example, one of these problems took the form of an enormous Black homeless man named Anthony. Anthony pseudo-ruled Nichols Park for the two years I lived there and he would often prowl E53rd St swinging a large wooden club. However, during the winter of 2020 his favorite spot to hangout was at the corner of S Dorchester Ave. This happened to be the corner I needed to walk past in order to access anything. So on many occasions as I went to buy coffee from a Dunkin or ice cream from the BaskinR obbin’s (made famous by Barak and Michele’s first date), Anthony would be sitting there, sometimes with his club sometimes not, and as a form of greeting he would often spit at me and ask “what’s up, Tall White Man?”

I had no recourse in those months. Violence was obviously not an option. But even if I had wanted to do something, in that paranoid time I feared a possible NYT headline derailing my dreams of academia far more than I feared a man with a club. The other mechanisms for justice (such as the police) felt equally unavailable to me — everyone knew who Anthony was and it was unlikely that I was the only person being subjected to his taunts. When I think back now it is more than anything the powerlessness I felt in those moments that has lingered with me. As far as I know Anthony still lives in that park, and he is still yelling at the Philz’s coffee employees or trying to steal people’s Taco Bell orders as he once did with me.

It was not only Anthony. Another “hidden” cost came in the form of a cacophony of random crime which would temporarily rock the neighborhood. One night in 2021 my wife, who was the assistant manager of a restaurant in the area, texted me to let me know that despite a failed carjacking mere feet from her, which had resulted in a man’s death, the restaurant would not be closing and I could expect her home at her normal time.

Or take January 9th, 2021, when Jason Nightengale went on a rampage beginning in Hyde Park and culminating in Evanston. Five totally innocent people were shot and killed (Yiran Fan, a 30 year old Chinese PhD student in a parking garage, Anthony Faulkner a 20 year old who was killed while shopping, Damia Smith a 15 year old girl who was killed in the backseat of her mothers car after he fired shots randomly into it, and Marta Torres a 61 year old women taken hostage and killed in an IHOP).

Events like these were too numerous to count and an entire book could be devoted just to cataloging them.

Bronzeville was, even relative to Hyde Park, a totally different world. The apartment we lived in had recently been remodeled and we were the first tenants to move in that summer. I recall sometimes sitting on my balcony in those early months and having the impression I lived on an island surrounded by a sea of decaying buildings on every side.

What had drawn us to the apartment was its affordable price and proximity to both of our respective places of work. Although my experience in Hyde Park had been relatively negative, my impression at the time was that this was primarily driven by racial hostility created by BLM and the crime spike it had produced — so hopefully by then the racial tensions would have abated significantly. On the one hand this ended up being true and while living in Bronzeville, I experienced relatively less direct (or, at least, overt) hostility for being White. But what replaced it was an ambient atmosphere of violence which was, to me, far worse.

It was a regular nightly occurrence to hear the rattle of machine gun fire shatter the night air, and one time a car peeled down our street just firing shots randomly. Across from my house and within eyesight was Walter H. Dyett Highschool for the Arts, and one day while reading, I saw a body slumped upon the ground surrounded by what seemed from a distance to be blood. Ambulances arrived and the lifeless body was whisked away. I have never been able to find a news story about this event but the memory of kids walking down that same sidewalk only hours later will haunt me for the rest of my life.

That high school was nestled at the north end of Washington Park, a greenspace I would often cross on my walk home from work. Later in the same month during which I had seen the body, I discovered the park itself had been the location of unspeakable crimes. Between 2001 and 2018, a total of 76 women had been stripped naked and strangled to death, their bodies found along the same paths I would then walk. They had been left in snowbanks and garage bins, and each of them had died like the powerless always do: silently. To this day 51 of their cases remain unsolved and the police have no leads.

It was in the context of these events that I made the decision to attend Stanford over the University of Pennsylvania for my PhD program. Upon arriving in Palo Alto, the calm which so many of my classmates felt was stifling came as a relief to me, and by contrast my immediate impression of Philadelphia was that it was a city much like Chicago. I knew which option I preferred and I have continued to live in the suburbs ever since. Even now I live nearly an hour outside of DC in no small part because I have vowed to never make the same mistake again.

There was a lot I loved about the South Side and many of the people I got to meet including my neighbors and my wife’s coworkers, who were incredible Humans. But if given the option to pay more to avoid the sound of machine gun fire and to ensure my children never have to file out of class on a sidewalk which was recently drenched in blood, I will continue to pay for that privilege. My ability to escape the clutches of a place like Bronzeville does not mean it ceases to exist, and our tolerance for violence — because it is, to us, invisible — is a sign of nothing but cowardice.

To defend the interests of the citizens of this country and to bring peace, prosperity, and felicity are the only objectives of the American government. It has no other tasks and serves no other purpose. Failing to do that is failing — full stop.

“We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

Your premises are sound. The revolving door of non-incarceration needs to stop. Glad Kim Foxx is finally gone.

"Our problem is one of an unwillingness to enforce the rule of law, and one of a deep culture of violence in this country, accelerated by the prevalence of guns, not material poverty."

I'm not sure "prevalence of guns" is causative- N.B. in the UK they just swapped guns out for knives. Here, like places in downstate Illinois, there're lots of guns, but low crime.

We did try the eliminating poverty aspect with "The Great Society" and things got worse. What needs to happen are two things IMHO:

1. criminals need to be incarcerated for a long time or take a short drop with a sudden stop- pour encourager les autres.

2. people need to be invested in their communities through employment, religion or both. It's more a cultural problem than an economic one. Bronzeville was a better place in the pre LBJ.

I have this theory that both parties are soft on crime for distinct reasons, both rooted in their respective forms of libertarianism. On the one hand, many people are total softies on guns, way more than is reasonable given the bulk of evidence on the links between guns and crime as well as being anti-tax which puts a ceiling on what is even achievable through public policy.

On the other hand, the left-wing term for libertarianism is just anarchism, which basically means that the government causes crime in the form of dubious causal analyses that suggest that police in fact increase crime, basically getting the causation backwards.

I suggest to liberals something of a norquist-pledge: Liberalism implies a huge role of the government in daily life, and I reject any and all forms of libertarianism. Crime should be taken as seriously as poverty is.