American Solvency Requires Autonomy

We can either accept inevitable austerity or grow our way out of this mess

In our previous articles we have focused on how we can best pursue an autonomous future as well as the important role it will play in any geostrategic competition with a country like China. However, in this article we wanted to pivot a little more towards why we think autonomy is so important and why pursuing an aggressive policy towards it is the correct move.

In short, America’s fiscal math doesn’t add up and our options are to either accept inevitable austerity or grow our way out of this mess; of all the tools we have available to jolt the economy into gear, autonomy, despite the risks, is the best.

Current Situation:

The postwar model of America is simply unsustainable. All of the institutions and social safety net programs in this country were designed for a world with radically different economic and demographic facts, and every attempt at structural reform has been blocked by atrophied political institutions.

In 2025, the U.S. is on track to run a deficit of nearly $2 trillion, adding to a debt load that, as a share of GDP, is already the highest in American history. Interest payments alone now consume almost 20% of federal revenue—larger than the defense department—and that share is only set to rise.

The solvency issue is most salient in Social Security both because it represents the largest single line item in the U.S. budget and because it has been reliably predicting its own bankruptcy for decades to no avail. Based on the most recent report by the Board of Trustees, the “Trust” is on track to totally run out of money in 2033, at which point either payouts will be cut by over 20% or alternative sources of revenue will have to be found in the general fund.

At the heart of the problem is a changing demographic profile: in 1945 there were 41.9 workers for each Social Security beneficiary and outlays represented only 0.29% of federal spending. By 2025 the ratio had fallen to ~2.6 workers per beneficiary and the program consumed roughly 22% of all spending.

Since the fundamental problem is a falling share of working-age adults, the most direct way to address this is by increasing per-worker output. This is exactly what autonomy would do since it would allow our economy to produce more with less human labor.

Rather than automation in principle, we could pursue other mechanisms to boost the economy such as substantially increasing immigration. High-skill immigration in particular is part of any basket of potential solutions to America’s solvency crisis, but in our current political environment it seems unlikely we will open the floodgates to migration.

Not only this, but even as America achieved the highest in-migration rates ever our financial situation continued to deteriorate apace. Finally, since immigrants assimilate to low birthrate patterns, society is forced to operate as a pyramid scheme of sorts with social programs paid for via perpetually high levels of immigration—which brings inevitable cultural tension.

It is therefore the sincere belief of the Boyd Institute that autonomy presents the best opportunity to increase productivity growth rates and in turn metaphorically right the ship of state finances.

There are risks:

This transformation will come with serious risks and disequilibrium effects as jobs are automated; the Boyd Institute does not want to act as blind cheerleaders without acknowledging that reality. We are fundamentally pro-human, and everything we advocate for is in the interest of general human flourishing. Doing this right has enormous potential to unlock the next era of American dominance. However, it must always be balanced against the tradeoffs which will inevitably exist.

We are already seeing these costs in many white-collar professions which are slowly being automated. Take, for example, the recent NYT article about Manasi Mishra and other recent CS graduates who have been unable to find jobs.

Simultaneous to the collapse in new-grad hiring, rumors are coming out of Silicon Valley that top AI researchers are securing contracts worth over a billion dollars. The coming age will be one of asymmetry, with all the pros and cons associated with that fact.

As we wrote about in a previous article for Boyd, most of our time has been focused on the world of bits, and this means that the AI transformation has also begun there. However, autonomous systems will mean this disruption spreads to physical sectors of the economy—manufacturing and transport, etc.—that have so far been relatively resilient to an AI of bits.

The solution is, however, to address the pain created by automation directly rather than shut down progress. For people who lose their jobs perhaps this could take the form of a UBI, but at minimum we need to do more to provide assistance with retraining.

It isn’t all bad:

Automation isn’t just about suffering and risk; it also provides an opportunity to expand the scope of human freedom radically. Just as the Industrial Revolution’s process of mechanization dramatically increased human living standards, automation could do the same in 2025.

We all have far more free time and agency today than an average person could have imagined in the past because many activities that once consumed the lion’s share of their time, such as farming, appear almost invisible to the modern world. Yes, that meant those jobs largely disappeared, but in retrospect this transformation has been overwhelmingly positive.

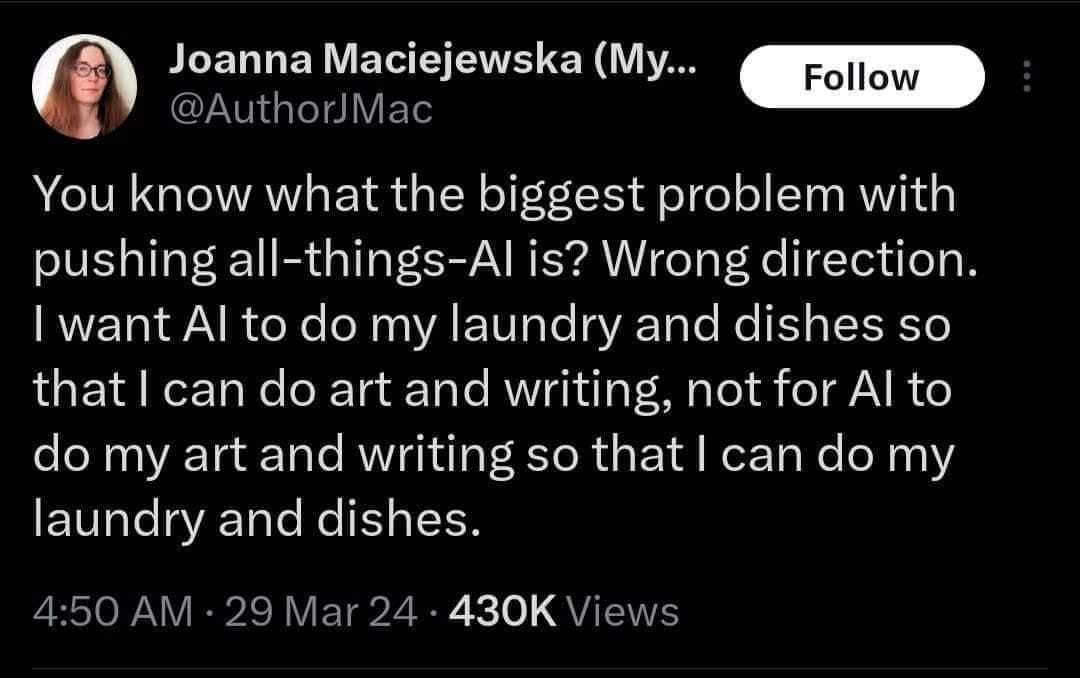

The more we can integrate robots into our lives to do stuff like clean our homes, cook our food, deliver our groceries, etc., the more time we can devote to other, more productive and interesting things.

Much as the washing machine or the automatic thresher unlocked millions of hours of time that was once spent in backbreaking labor, autonomy can do the same again.

Conclusion:

An autonomous revolution will bring complexity and risk, but decisions must always be made in the context of the next best alternative—and doing nothing consigns us to austerity, stagnation, and decline. Autonomy is not a silver bullet, but it is the most powerful lever we have left to restore growth and preserve solvency.

We truly stand on the precipice of what could be the greatest era in human history. Whether it becomes an age of flourishing or fracture depends on our willingness to embrace change, manage the risks, and commit to building a future worthy of our species.

A few thoughts:

- A portion of the social security fund should be invested in the S&P 500. It’s dump that it’s only invested in US treasury notes which have a horrid return of 4% - this would probably give us more time to figure out a /real/ solution. I’m pretty sure bush jr wanted to do this, or maybe it was Clinton idk.

- White collar workers are already being pinched by the stream of unnecessary H1Bs (check Twitter, it’s big news that companies have been secretly advertising jobs in such a way that native Americans did not apply - this is changing) so I wonder how much of the current displacement is AI driven vs H1B…

- How can we advance automation while containing its destabilizing effects? I don’t think we can. If we look back to the Industrial Revolution any retroactive attempt to maintain the subsistence farmer lifestyle would have delayed the massive gains in quality of life that capitalist society (later) brought. I say we go full steam ahead and endure the upheaval as quickly as possible.

The problem with this scenario is the same as all the fantasies of the AI crowd. A small group gets fantastically wealthy and millions lose their jobs but are freed up to be more productive through “job training”. But the unanswered question is what jobs will they be trained to do. I have not yet seen a plausible answer to that question