Does Immigration Raise Housing Prices?

Evidence from Danish refugee resettlement data.

Recently an economics working paper has been making the rounds that purports to show immigration is the primary driver of home price increases in Denmark over the last 20 odd years.

It isn’t surprising that this research has struck a nerve since it feeds directly into one of the more popular narratives on the online right today—specifically, that “we are a nation, not an economy” and that immigration is a major driver of the housing crisis. Given that many people are talking about this paper right now, and given the general level of interest in the topic of immigration, we feel it is worth taking the time to carefully go through the research and outline what it does—and does not—actually show.

Today I will not be assessing the credibility of the thesis on immigration and housing affordability on the whole, but if you are interested in learning more about the topic as it relates to housing, we recently took the time to steel man the case for it—as well as the other possible “housing pills”—in an article you should check out.

In addition to going over the paper, I’ve also taken the time at the end of this article to outline how I read economics research—as a dropout biz school PhD. I’ve done this in an effort to demystify the process, since I sincerely believe that reading research as a layperson isn’t all that complex if you just know what to look for.

Breaking Down Damm et al. (2025)

High-Level Summary of the Study and Findings

The paper, titled “Medium-Run Impacts of Immigration on the Housing Market: Evidence from a Quasi-Experimental Shift-Share Instrument,” studies how inflows of immigrants—specifically refugees—affect the housing market in the medium run (over several years) in Denmark. The authors approach this topic from a classical economics perspective and outline both how immigration is expected to impact prices, as well as ways in which the standard model might fail to capture reality. In their own words:

“A population shock, like the one induced by an immigrant influx, increases, ceteris paribus, the demand for housing units, which together with a fixed housing supply translates into higher rents in the short run. For a given market capitalization rate, investors will demand higher prices for their properties in the asset markets, thereby incentivizing construction activity. As time passes, the increased housing development will enlarge the stock of housing. A higher supply of housing units will therefore dampen the initial rent spike. In the long run, the higher population will result in a new long-run equilibrium in the housing market characterized by higher rents, higher prices, higher construction rates, and a higher stock of housing.”

The authors focus on two ways this model can be expanded upon, specifically whereby immigrants “do not affect housing prices or rent over the long run.” The theoretical extensions proposed to understand this outcome are: 1) native out-migration from the urban area; and 2) local immigrant-specific amenities that affect the degree of competition in the local housing market.

In other words, all else equal, immigration should drive up housing prices. However it might actually not if people move away from immigrant-heavy areas (reducing prices locally), or if people have other reasons to cluster together—“immigrant-specific amenities”—which might change location choices.

In order to study this empirically, they use a “shift-share” design.1 Specifically, they use a modified version where Denmark’s national refugee forecasts serve as the shift, and each municipality’s 1995 share of refugees serves as the share. Multiplying these gives a predicted immigrant inflow for each area that’s independent of local economic conditions and thus plausibly exogenous.

This is only possible because of a convenient quirk in Danish refugee immigration policy. Between 1986 and 2016, Denmark assigned refugees to municipalities on a quasi-random basis. There was a change to the formula in 1999, so the research focuses on the later period. Because the assignment was exogenous, researchers can identify causal effects relatively cleanly.

What They Find

In the medium run, areas that received more immigrants saw substantially higher housing costs. They examine this effect at both the municipality and neighborhood levels, and the results are mostly consistent—though they differ in scale.

At the municipality level, an immigration influx equal to 1% of the local population caused about a 6% increase in rents and an 11% increase in house prices within five years. At the neighborhood level, the effect is smaller—roughly 1–2% increases in rents and prices for a 1% population influx. This is because native Danes appear to “flee” neighborhoods where refugees are resettled, moving to other parts of the same municipality, dampening the localized price effect.

A quick stylized example is useful (to be clear the numbers I’m using are not reflective of those in reality as I am merely choosing illustrative values).

Let’s say there’s a city with only two neighborhoods and each one has homes which cost $100 on average. For now we can assume each neighborhood comprises half the city’s total population—but the neighborhoods’ relative shares of native versus immigrant populations can change:

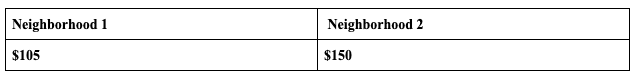

Now let’s suppose there’s an immigration surge created by refugee resettlement to Neighborhood 1. Following the surge, the new prices look something like this:

At the city level, prices rose by 27.5%, but the majority of that increase occurred in Neighborhood 2. Why? Because higher-income Danes relocated away from Neighborhood 1 (the refugee neighborhood), pushing up prices to a larger degree in Neighborhood 2.

This pattern—where immigration prompts native relocation, thereby muting neighborhood-level price effects—is well-established in the literature, with studies such as Accetturo et al. (2014) and Saiz & Wachter (2011) reaching similar conclusions.

Stepping back from the neighborhood-level dynamics, the study finds that immigration was the major contributor to Denmark’s housing price increases between 1999 and 2016. The authors estimate that roughly 62% of the overall house price increase in Danish municipalities over that era can be attributed to immigration inflows.

So this appears pretty damning: at least in Denmark, most home price appreciation seems to result from immigration—and where it’s dampened, it’s only because of native Danes “fleeing” to more homogeneous neighborhoods.

However, caution is warranted before declaring the evidence decisive. There are nitpicky empirical criticisms, but the main issue is the source of variation. This study specifically looks at refugee resettlement in Denmark; extending these general effects to, say, a Chinese chemistry professor moving to Boston isn’t obviously valid. Moreover, one reason prices rose so much in Denmark was limited supply elasticity—on both public and private fronts. Since little new housing was built, the counterfactual world with adequate supply buildout remains unobserved.

It’s a fascinating paper, and more academics should take on topics this complex. But it should be read for what it is—and not more.

How to Read an Economics Paper

Before continuing, I just want to say that LLMs are an incredible tool for breaking down academic research, and you should feel no shame in using them. If you’re a professor or intend to use the research as a centerpiece of an argument, then, of course, read the paper fully. But if all you wanted was the abstract but more in-depth, a tool like ChatGPT is an upgrade.

If you intend to read the paper yourself, the key question is what you want to get out of it. This matters because you can safely skip large portions depending on your goal—economists structure papers predictably.

Most economics papers follow this layout:

Abstract

Concise summary of main results

Introduction

Overview of the entire paper

Institutional Details and Prior Research

Data

Empirical Design and Results

Conclusion

They may name these sections differently (e.g., Damm et al. 2025 does), but the structure is consistent. Knowing this lets you jump directly to relevant parts and save time.

There are three main reasons someone might read an academic paper:

To add a citation to an article

To learn about the world

To extend the research or use its methodology

If you’re citing, just read the abstract and introduction. That alone gives you 90% of what you need.

If you want to learn about the topic, also read the “Institutional Details and Prior Research” section. This situates the paper vis-à-vis the broader literature—there’s no economics paper that stands alone, and every study builds on decades of prior work. Reading this section helps you grasp the conversation you’re entering and find related papers worth exploring.

If you have a background in statistics, skim the empirical design and results sections, then review the conclusion.

Finally, if you intend to extend the research or apply its methodology, read the entire paper carefully. By that point, you’ll likely already be familiar with the literature, so focus on the data and empirical design. And again—don’t hesitate to use tools like ChatGPT to clarify technical sections.

The key takeaway: an academic paper rarely provides a complete answer. Economics, in particular, studies narrow empirical questions, and generalizing results (as in Damm et al. 2025) is always risky.

Essay Contest

As some of you may know, we are currently holding an essay contest on solutions to the housing crisis. If reading this article sparked any ideas, I encourage you to write up your own answer! The top prize is $2,500, and the contest closes October 31st.

A “shift-share” design in economics is an empirical strategy used to analyze the impact of aggregate shocks (such as industry-level demand or trade shocks) on various regions or sectors by combining information on regional “shares” and macroeconomic “shifts”.

All else equal, it seems reasonable to think an increase in demand would tend to cause an increase rather than decrease in prices. Unless you have a deep-seated ideological urge to believe otherwise.

I think it’s very instructive to look at a cost breakdown on new build housing. When I built in my small town in the exurbs it looked something like:

Labor and materials: 40% (I don’t remember but let’s say it was half labor and half materials)

Land: 25%

Taxes, impact fees, sales cost, etc: 35%

So the labor cost of the house was only 20%. This is why when people say “what will the cost of housing be if you don’t have all those immigrant construction workers” doesn’t make much sense to me. If I think the immigrants are driving up things like land, taxes, and fees then even if that 20% labor gets a boost I’m losing on the rest of it.

Id add too that property taxes are a cost of housing. Over thirty years they will add up to 30% in a low tax area and 60%+ in high tax areas.