Weekly Roundup #11

Housing | Ackman, agglomerations, and more

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Welcome back to the Boyd Institute’s roundup series. This week we published the second part of our four-part series on precisely why housing policy should be targeting young, middle-income households.

In the third part of this series which will be published in the upcoming week, we will be discussing existing housing policy regimes — at the federal, state, and local levels — that are in large part boxing out young middle-class families.

Now for this week’s roundup we have…

Newsflow:

On Bill Ackman’s latest pitch to the president on IPO-ing Fannie & Freddie

On more rent control in Los Angeles

On jobs and housing being caught up in a doom loop

Academic research:

On supply elasticity and how housing policy affects local neighborhood prices, not just citywide aggregates

On agglomerations — how labor productivity interacts with density, and how this interaction changes based on the human capital mix

Additional reading:

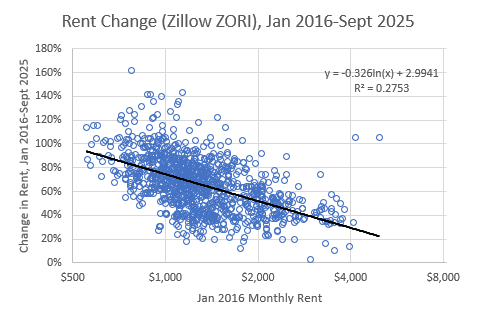

On how rents have (perhaps ironically) risen the most in the least expensive areas

NEWSFLOW

WSJ — Bill Ackman Says He Wouldn’t IPO Fannie and Freddie Right Now

The Trump administration for months has been discussing plans to list the mortgage giants’ stocks, and the CEOs of the six largest banks in the country have pitched the president to be a part of the offering.

Billionaire investor Bill Ackman has a different idea he pitched to an audience on X Tuesday. Instead of selling stock, he says the Treasury should agree to cancel the government’s senior preferred shares and exercise its warrants to purchase nearly 80% of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac common stock. Fannie and Freddie could then move their shares from the over-the-counter market to the New York Stock Exchange.

That’s fair given the Treasury has recouped all the cash it invested in Fannie and Freddie plus about $25 billion more than what it was owed in dividend payments, Ackman said, adding that this re-listing could happen as soon as this year. Ackman’s plan benefits common stock holders, and a large one of those happens to be his own hedge fund Pershing Square.

Politico — Los Angeles limits rent hikes in historic vote

For the first time in decades, the Los Angeles city council overhauled its rent control rules on Wednesday, sharply lowering the annual rent increases facing tenants in one of the country’s most expensive cities.

Under the new rules, Los Angeles landlords whose buildings are covered by the city’s rent stabilization laws — about three-quarters of the market — will be allowed to increase rents by between just 1% and 4% each year, depending on inflation. Currently, landlords are allowed to increase rent between 3% and 8% annually.

Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass applauded the council’s action, saying that it’s part of her broader focus on making it easier to live in the city. “We will help Angelenos afford their housing, prevent people from falling into homelessness and restrict skyrocketing rents,” Bass said in a statement.

Over 1.5 million Angelenos live in the city’s 651,000 rent stabilized apartments. Generally, the limits on rent increases apply to apartments built before October 1978.

State law prevents the city from changing that date, though landlords of more recently built apartments in Los Angeles and elsewhere in California must abide by less stringent rules prohibiting larger rent hikes. Single-family-home rentals and apartments built within the last 15 years are exempted from rent controls except in special circumstances.

Bloomberg Opinion (Conor Sen) — Job and Housing Stresses Are Caught in a Vicious Loop

The housing market has been in the doldrums for three years, so it’s easy to assume there’s nothing new to the weakness there. That’s a mistake. The deterioration in housing has taken a fresh turn in recent months with important implications for the economy, particularly given growing skepticism within the Federal Reserveabout a interest rate cut in December.

I noted after the Fed’s September meeting that mortgage rates at 6.25% were not sufficient to fix the housing industry’s woes. Some 1.5 percentage points of easing over the past year or so hasn’t resurrected demand enough to stabilize homebuilder profit margins or reduce the incentives they need to offer buyers. The companies are responding by reducing construction, land purchases and headcount.

A bad chicken-and-egg dynamic is at play here. A sluggish labor market has made people reluctant to buy homes, even as affordability improves; while poor homebuying demand is leading builders and other housing-linked companies to lay off workers, further weakening the labor market.

Executives at Beazer Homes USA Inc., the most recent homebuilder to report earnings, said last week that they have been able to rebid material and labor costs over the past year to save about $10,000 per home — meaning their suppliers and trade partners have had to eat costs to stay busy. The company also cut headcount.

ACADEMIC RESEARCH

The Intergenerational Transmission of Housing Wealth

Daysal et al. (2025)

This paper answers a fundamental question about how parental wealth advantages get passed down to adult children, and specifically identifies which mechanisms matter most. Earlier studies showed a strong correlation between what parents own and what their adult children eventually accumulate, but the actual pathways through which housing wealth helps children remained unclear.

This paper shows that housing-wealth gains accruing to parents when children are 0–11 are causally transmitted at rates of 15–27% into the child’s adult wealth, while gains during the teen years have no measurable effect. What is even more interesting is that 60-80% of this wealth transmission operates through mechanisms beyond direct cash transfers — education, earnings, and household environmental effects from improved parental financial stability that all reshape children’s life trajectories.

The research also reveals substantial heterogeneity — parental housing wealth changes during middle childhood (ages 5-11) produce particularly strong effects, suggesting that the period when children are forming social networks, educational foundations, and peer relationships is when financial stability matters most. For policymakers, this suggests that housing affordability interventions targeted at young families with children could generate outsized returns on investment by improving multiple dimensions of child development simultaneously.

The Complementarity Between Cities and Skills

Glaeser and Resseger (2010)

This paper directly identifies a crucial nonlinearity in how agglomeration effects operate: the relationship between city size and productivity differs dramatically depending on the human capital composition of the metropolitan area.

In the most well-educated third of metropolitan areas, area population size explains approximately 45% of the variation in per-worker productivity. The elasticity of output per worker with respect to population is ~0.13, meaning a doubling of metro area population correlates with roughly a 13% increase in per-worker productivity.

In the least well-educated third of metropolitan areas (bottom 100 MSAs by share of college-educated adults), there is virtually no correlation between city size and productivity.

This finding overturned the conventional assumption that agglomeration effects are uniform across cities. The same density that drives massive productivity gains in Boston or San Francisco generates no measurable benefit in lower-skill metros.

A critical insight, however, is that human capital differences alone do not fully explain the city size-productivity relationship — that unobserved skills (skills not captured by education measures) might be higher in larger skilled cities. The authors estimate that unobserved human capital could explain at most 30% of the city size effect in skilled metros, leaving at least 70% unexplained by human capital alone.

The paper found that physical capital is not the explanation. But if skilled workers moved to large cities purely for amenities, we’d expect their real wages to be lower (because they’re paying for those amenities). Instead, real wages rise with city size in skilled metros, implying workers are compensated for being there — suggesting genuine productivity gains rather than amenity consumption.

ADDITIONAL READING

Rising Incomes Mask a Hidden Housing Squeeze That Hits the Bottom Hardest

Mercatus | Kevin Erdmann

Rent in the most affordable ZIP codes has increased by about 50% more than rent in the most expensive ZIP codes. Think of it this way. Over the past decade, about one-quarter of the variance in rent has vanished. Another 3 decades like this, and every home in America would rent for $4,000 per month.

Note, for those who, like me, appreciate the broader point being made here, it is tempting to respond to this by saying something like, “Everyone wants a single-family home in the suburbs on a quarter acre lot. Not everyone can have one, so the price just gets bid up.” This is a common reply.

It couldn’t be more wrong. The homes that are least favored in the worst locations are the homes with the most rent inflation. You can’t explain this with preferences. Unfortunately, economists primed us to have that wrong reaction when they explained rising costs in New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco with agglomeration value. Agglomeration value is real.

It just isn’t the cause of our housing cost problem. When rising costs were limited to those regions, costs were rising the highest in the least favored neighborhoods, and families were flooding out of those cities out into the rest of the country. Now those cost patterns are everywhere. Figure 2 has no controls for regional fixed effects. It doesn’t matter if it’s the Rust Belt or the Sun Belt or the coasts.

Rents are rising the most in the least favored neighborhoods in every region. Every region didn’t suddenly gain agglomeration value. Every region suddenly started building homes at the same low rate that New York and Los Angeles had been.

[…]

As long as housing supply is bad enough to obstruct household formation, rents in every city must rise until the number of delayed households increases enough to match households to homes. Some of that works out still through regional displacement, but in the aggregate, somewhere, there are thousands of households not forming each year that would have formed under the economic quality of life that was normal in the 20th century.

Maybe those families aren’t worse off in absolute terms each year compared to the year before. But they are worse off enough to give up on a standard step in the life cycle of a normal modern human being. It is understandable that they think the economy isn’t working. It is understandable that they think it’s rigged. And telling them otherwise will only serve to damage our own credibility.

It pains me to say that because those who are prone to “fixed pie” thinking don’t think growing the pie is an option that will improve their economic lives. Those who normally think the economy isn’t improving for everyone won’t become allies on the solutions needed to unrig the system. They will call that “trickle down” thinking. So, it serves less of a political purpose to acknowledge this problem than it should. But, we must first and foremost strive for seeing things truthfully, regardless of the politics.

https://www.housingwire.com/articles/beazer-homes-shifts-to-move-up-buyers-bets-on-energy-efficiency/