Weekly Roundup #13

Housing | Office-to residential, gentrification, California Forever, & more

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Welcome back to the roundup series. Earlier this week we published the fourth and final part of our series on why housing policy should be optimized for young, middle-income households. This article laid out our specific policy proposals that optimize for the growth of the housing cohort with the highest social (and fiscal) multipliers: young, educated, middle-income families.

Please do check out our proposals, we’d love to hear everyone’s feedback! Now, for this week’s roundup we have…

In the news:

On the boom in NYC office-to-residential conversions

On the persistent disconnections in the current housing market

Academic research:

On the real effects — contra popular narratives — of gentrification

On the negative economic collateral damage from falling housing affordability

Additional reading:

On legendary housing economist Ed Glaeser’s take on “California Forever”

IN THE NEWS

Office-to-Residential Conversions Are Booming and New York Is the Epicenter

WSJ | Brian McGill, Max Rust, Peter Grant

Over the past two decades, developers in New York have converted nearly 30 million square feet of office space into residential living, with the pace of transformation picking up in recent years.

To encourage even more conversions, the state legislature last year approved new tax abatements. As many as 25 future office conversions with 8.8 million square feet of space are in the planning stages throughout Manhattan.

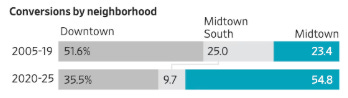

The city, meanwhile, approved zoning changes, greatly expanding the number of buildings eligible for conversions. Since the pandemic, half of all conversions announced are in Midtown.

Even the pickup in conversion will make only a small dent in New York’s more than 75 million square feet of surplus office space. But Manhattan has one advantage other cities can’t match: a rental market with median $4,500 monthly rents for a one-bedroom.

Design breakthroughs pioneered in Manhattan will likely accelerate the pace of conversion in New York as well as the rest of the country. The national pipeline currently includes 78,500 units, up from 23,000 in 2022, according to RentCafe.com. And as these projects multiply, the playbook keeps expanding.

“There are more case studies that prove the naysayers wrong,” said Robert Fuller, principal of Gensler.

A Historic Housing Disconnect Is Forcing Prices Down

Bloomberg Opinion | Conor Sen

When new homes start selling at a discount to resales, it’s a market signal worth heeding. Apollo’s Torsten Slok recently highlighted the anomaly — the first in over 50 years. The new-home market has become the clearest barometer of today’s difficulty: builders spent about 7.5% of sale prices on incentives in the three months ended August, per John Burns Research & Consulting, surrendering the 16% premium new builds have typically enjoyed since 1973.

Comparing new and existing homes is illuminating because the former is a straightforward build-and-sell business, while the latter is clouded by distortions. Nationally “stable” resale prices obscure deeper deterioration. Sales have hovered near 4 million annually for three years even as inventory has climbed back to 2019 levels, with wide regional variation. Days on market continue to lengthen as sellers misprice and then choose between cutting or delisting — a trend now accelerating into year-end.

The constraint on buyers isn’t simply mortgage rates but broader unaffordability and a fragile labor market. Sellers assuming spring will bring relief may be misguided. Builders made the same bet — that structural undersupply and future rate cuts would revive demand — only to be met by persistently weak sentiment and the need for escalating incentives. With elevated inventory, strained affordability, and shaky consumer confidence, downward pressure on home prices is likely to persist until something closer to 2010s-era affordability returns.

ACADEMIC RESEARCH

Rents, Movers, and Stayers: The Spillover Effects of Construction in San Francisco

Pennington (2025)

This paper touches on a contentious debate in housing policy: does building new market-rate housing actually help existing residents, or does it drive displacement and gentrification? Using an ingenious natural experiment — building fires in San Francisco that randomly induced construction in some neighborhoods but not others — the paper finds that renters already living within 100 meters of new market-rate construction see rents fall by approximately 2% relative to trend. More importantly, their risk of displacement to a lower-income neighborhood drops by 17 percent. The benefits are real but geographically circumscribed: they decay linearly to zero within 1.5 kilometers.

This directly challenges the displacement narrative that dominated affordable housing advocacy in recent years; increasing supply of housing, even market-rate housing, puts downward pressure on rents for everyone. Landlords facing new competition can’t simply raise prices and they must compete on the margins that matter to renters. The study shows that this happens in tandem with another effect, that is a “concentrated demand effect,” whereby within 100 meters of new construction, building renovations and business turnover spike dramatically. Neighborhood quality improves visibly — new restaurants, better-maintained properties, more activity.

So, gentrification, according to Pennington’s findings, follows this pattern: parcels within 100 meters of new construction are more likely to experience net inflows of higher-income residents. This is happening simultaneously with rent declines and reduced displacement. Both things are true. Rents are falling for the people who stay, even as the neighborhood composition shifts toward higher-income households.

“Giving Up”: The Impact of Decreasing Housing Affordability on Consumption, Work Effort, and Investment

Lee and Yoo (2025)

Housing affordability has become so constrained that many younger Americans are no longer just delaying homeownership — they are giving up on it entirely. This paper that this surrender has profound behavioral and economic consequences that ripple across the entire life cycle. It finds that when renters perceive homeownership as unreachable, they systematically reduce work effort — among those with under $300,000 in wealth, 4–6% report low work effort, double the rate of homeowners. Simultaneously, consumption relative to wealth increases, and high-risk investments (including cryptocurrency) become alternative paths to wealth accumulation in lieu of traditional saving.

The paper’s most important finding is that these behavioral changes create what the authors call a “near-zero wealth trap.” Two renters starting with identical net worth can end up dramatically wealthier or poorer depending on whether they retain hope of homeownership, and this divergence transmits intergenerationally. Children of parents who gave up are more likely to give up as well, entrenching wealth inequality across generations.

The authors propose a targeted subsidy lifting young renters above the “giving-up threshold” by age 40, before behavioral shifts become entrenched. The welfare gains are 3.2 times a universal transfer and 10.3 times transfers to the poorest. More importantly, it raises work effort and reduces reliance on social safety nets.

ADDITIONAL READING

Clear a path for sweeping urban experiments such as California Forever

LA Times | Ed Glaeser and Chris Elmendorf

This fall, the backers of “California Forever” — a proposed 400k-person city 50 miles northeast of San Francisco — released their master plan, and it’s genuinely strange. It’s built on the exurban frontier but designed like 19th-century Brooklyn: dense grid streets, rapid transit, greenways, and apartment buildings up to 85 feet tall in the least dense neighborhoods. For context, that’s taller than almost every apartment building built before 1880. You’d be hunting for row houses in the middle of the Central Valley, not suburban McMansions.

This breaks all the rules of how exurban development actually works. The Woodlands, Texas — one of America’s most successful exurban projects of the past 50 years — is only 30 miles from Houston and is basically all single-family homes. Only in a state as desperately underhoused as California could you pitch people on apartments that are even farther from actual jobs.

But California Forever isn’t just betting that Bay Area housing costs have created a market for extreme commuters. It’s attempting something more ambitious: to operationalize three decades of urban economics research.

The key insight is that density makes everyone more productive. People living and working close together learn from each other, share risk, access thick labor markets, and benefit from shared infrastructure like airports or cultural institutions. Economists call this “agglomeration benefits,” and it’s real and substantial.

The catch: individual developers don’t capture these benefits. If my new apartment building attracts a restaurant that becomes wildly profitable, I don’t share in that success. So developers chronically underbuild density. Add NIMBYism on top, and you get perpetual underinvestment in urban housing.

California Forever’s big bet is different. By owning the entire city — residential land, downtown offices, manufacturing districts — the investors can profit from agglomeration. Early residential projects might lose money, but they’ll increase the value of downtown and industrial areas that the same investors own. Because they’re capturing the whole pie, not just individual slices, they have incentives to actually build good urbanism.

The problem? The permitting gauntlet is brutal. The project needs sign-offs from Suisun city, Solano County, and state water agencies, each with veto power. A Solano County supervisor has already told them to go somewhere else. And she might convince two colleagues to kill the whole thing.

California desperately needs millions of new homes. But a single county official shouldn’t be able to torpedo a project of statewide significance. The state uses “comprehensive permit” programs for clean energy projects—letting a single state official make the call rather than handing local governments a veto. That model should apply to transformative urban development too.

Excellent curation of the Pennington findings. The simultaneouus rent decline and neighborhood income shift is exactly the kind of nuance missing from both YIMBY and anti-displacement debates. What's underexplored is how that 100m decay funcion interacts with transit-oriented developement at scale, where concentrated demand effects might spatially compound in ways that fundametally alter localized equilibria.