15 Housing "Ground Truths"

Midway through our sprint, here’s what we’ve established.

Background:

Throughout our weekslong discovery phase, we’ve dug into the logical frameworks supporting competing narratives and squared those against a large body of academic research and empirical evidence in hopes of establishing a set of “ground truths,” or a set of baseline facts that will be foundational to coming up with bold, asymmetric policy ideas.

As we enter the latter half of our sprint, we thought it would be worthwhile to share where we’ve landed on the key debates taking place within the universe of “housing crisis” discourse.

1) Homebuilders are not the villain.

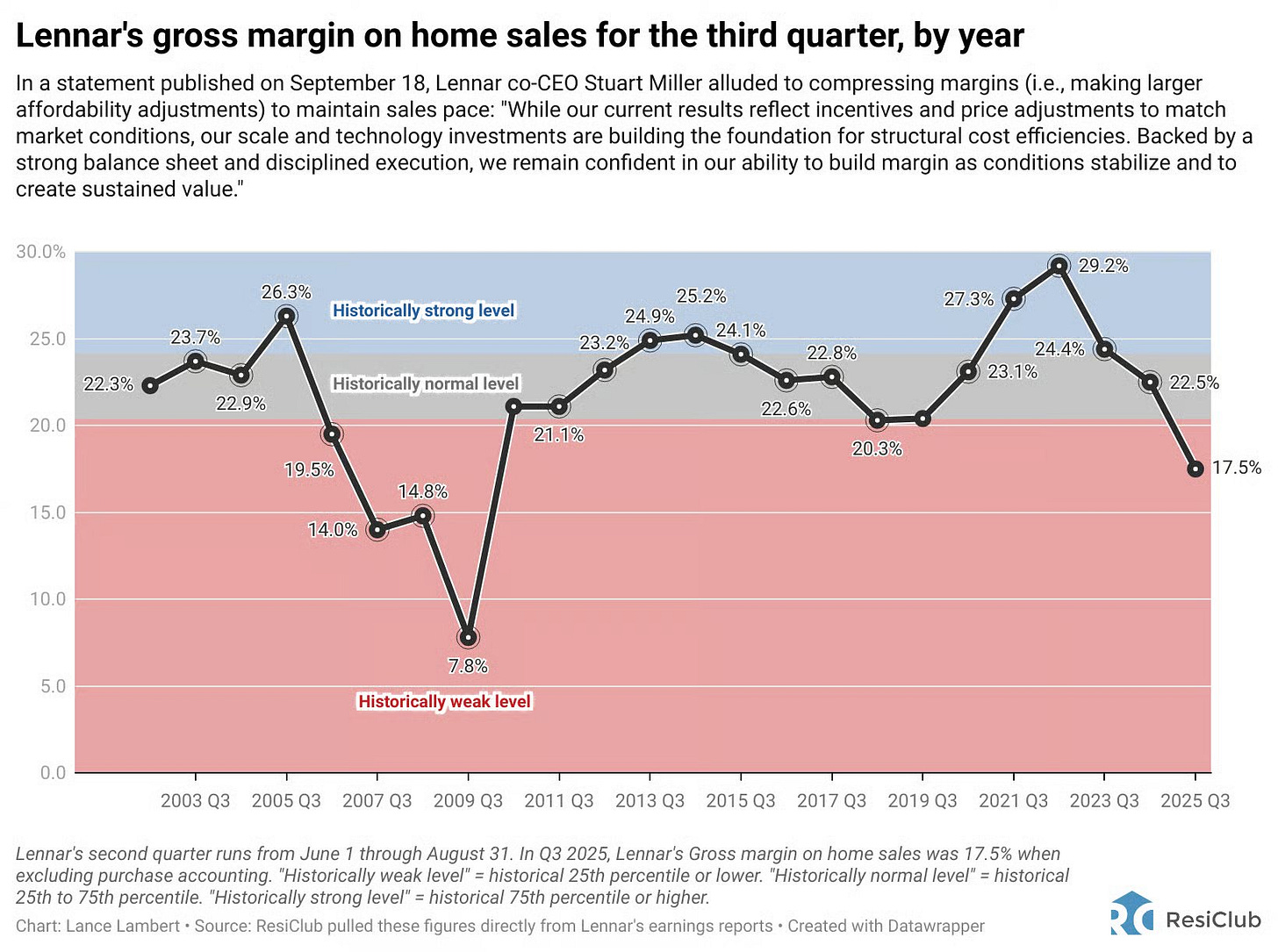

Homebuilding is a risky, capital-intensive, highly cyclical business. Major national builders like Lennar (and D.R. Horton and others) aren’t market-riggers; they’re rational actors navigating a thicket of regulatory and macro constraints. That their gross margins ballooned from 2021-23 simply reflected market conditions — the post-Covid housing demand shock — not anti-competitive behavior.

Since market conditions have normalized, Lennar’s margins have retreated to the mid-to-high teens (well below their long-term goal and around the lowest in seven years) amid tepid demand and rising input costs.

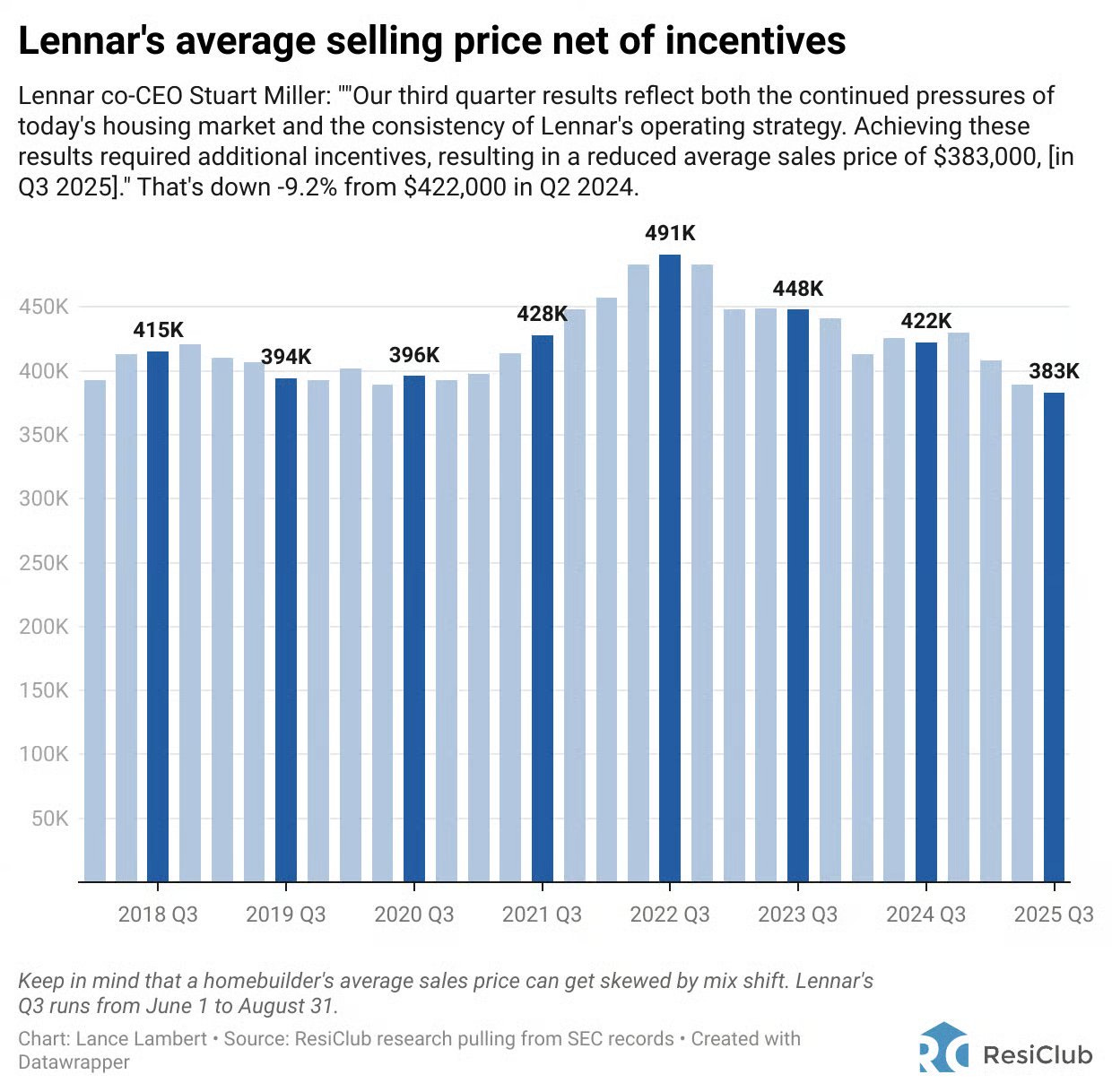

To bide their time, the builders have responded predictably: cutting production, slowing land acquisition, and shrinking headcount while leaning heavily on mortgage-rate buydowns and buyer incentives to move inventory in an increasingly skittish market. The result for Lennar has been the plummeting of its average selling price of a new home.

These developments — price deflation; margin contraction — are a sign of firms trying to preserve viability in a competitive market, not a cornered one.

The deeper dysfunction lies upstream in the swelling of labor and material costs, the politics of zoning, and the monetary whiplash that turned sub-3% mortgages into a structural trap. Builders are simply responding to developments in a market distorted by policy, not distorting it themselves.

2) Housing demand will almost certainly soften.

Over the past 30 years, increasing housing demand in the U.S. was driven by two primary factors: first, declining average household sizes; second, elevated immigration rates. For example, between 2016 and 2021, immigrants and children of immigrants accounted for over 75% of U.S. population growth.

In 2025, we are on track, according to the San Francisco Fed, to have under a million net migrants; some estimates show that America might actually experience net negative levels, an enormous reversal from the peak of 3.3 million a year in 2023.

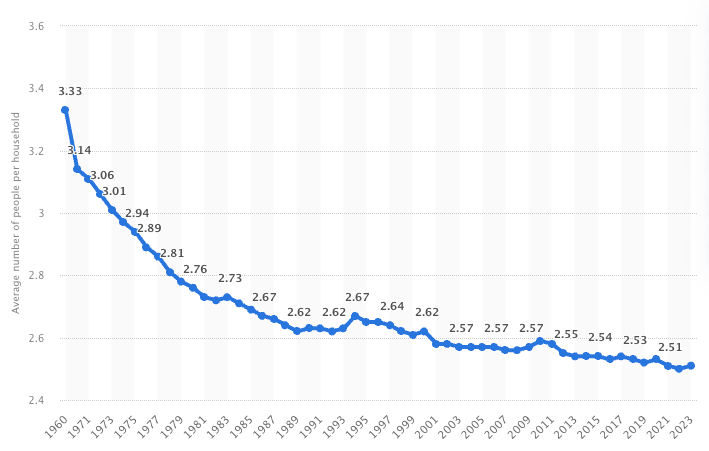

Similarly, the decline in average household size has slowed and could even reverse as older parents begin to move back home to live with their children.

Between 1960 and 2023, the average household size fell from a peak of 3.33 to a near low of 2.51, but most of this decline occurred in the late 1960s through 1990, with a second wave of household size declines happening in the 2010s.

When taken together, it is quite likely that America has already passed peak housing demand.

3) Market-rate (and “luxury”) housing construction unlocks affordable supply.

Supply skeptics — notably the political left — tend to treat market-rate development as irrelevant to affordability; the data says otherwise. Building new, higher-end units triggers a powerful “filtering” chain:

Been et al. (2019) showed that 23.4% of affordable rental units in 2013 had filtered down from higher-rent categories since 1985. This filtering was also shown to be faster in areas with fewer regulatory restrictions.

Mast (2023) tracked 52,000 residents of new buildings and found that building 100 new market-rate units leads 45-70 people to move out of below-median income neighborhoods within five years.

These affordability gains occur not through depreciation over decades, but through the dynamic turnover of people and housing stock. Essentially, new construction relieves pressure down the chain almost immediately. This doesn’t make market-rate construction a panacea — it still needs zoning flexibility, infrastructure support, and localized targeting — but it does mean “luxury” development can function as affordability policy, albeit with different connotations.

So the problem isn’t that we build too much at the top, it’s that we still build too little in general.

4) Institutional ownership of single-family homes is a net benefit to housing supply.

The caricature of Wall Street landlords “buying up America” obscures a more nuanced reality. The latest research shows that institutional ownership expands the rental stock:

Coven (2025) found that for each home purchased, institutions add an average of 0.58 units to the rental supply while reducing homeownership by just 0.23 units.

Barbieri and Dobbels (2025) found that institutional acquisitions increase average renter welfare by $2,760 per year (with rents decreasing by 2.3%). This net benefit reflects two opposing effects: higher concentration raises rents by 3.8%, but higher rental supply lowers rents by 6.1%.

Further benefits come from institutional ownership: they professionalize operations, renovate aggressively, and reduce vacancies — especially in neighborhoods previously dominated by small, less-efficient landlords. Analysis from the Urban Institute shows that institutional investors typically purchase homes in need of “around $20,000 in repairs,” prioritizing critical renovations such as roof and window repairs that improve health, safety, and sustainability for future tenants.

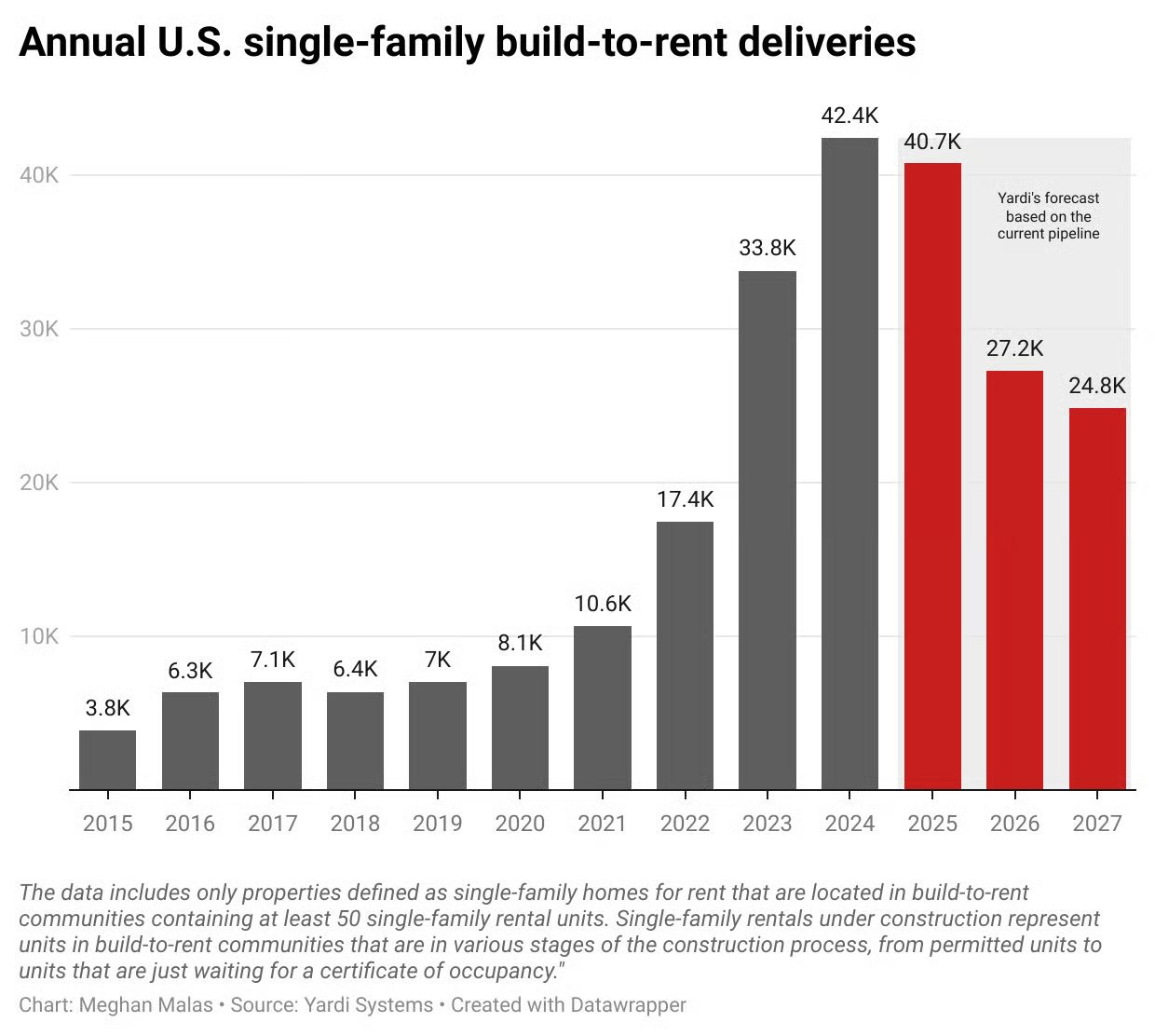

Critically, there’s been a shift. Institutional investors have been net sellers of existing single-family homes for six consecutive quarters (as of 2Q25), no longer injecting demand into this market — as they did en masse during the ZIRP era — but instead supplying it. Meanwhile, in terms of capital allocation, they’re pivoting to build-to-rent communities.

Rather than buying existing homes, major PE-backed landlords like Invitation Homes, American Homes 4 Rent, and FirstKey Homes have switched to building purpose-built rental communities. This transition reduces competition for small and traditional buyers while expanding rental supply — crucial in a market where many young adults are priced out of homeownership.

Additionally, given these institutions’ size and heft, they’re often able to force through projects that might have otherwise died in the review process — rendering the vertically-integrated developer→landlord business model economically feasible.

There are still important caveats about second-order effects in concentrated markets; Coven (2025) showed that institutional presence contributed to 21-23% of observed price increases in their top decile of markets. But the traditional narrative that investors are using market power to restrain supply is largely unfounded. Their market power exists but is outweighed by economies of scale that incentivize expanding rather than restricting rental supply.

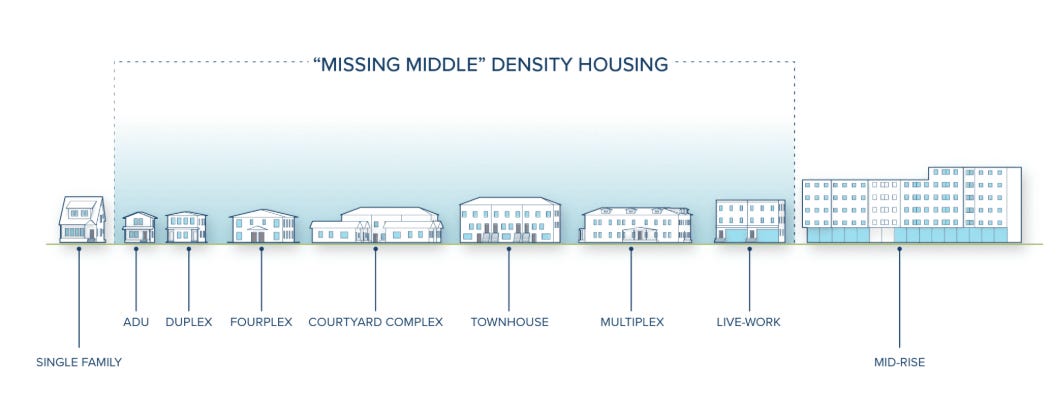

5) The “missing middle” is one of the most overlooked levers for increasing affordable supply.

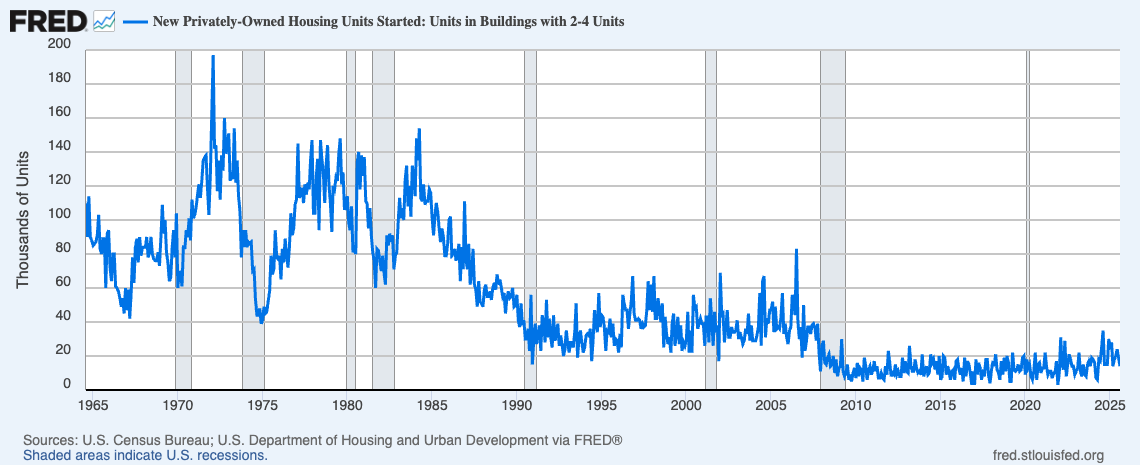

Duplexes, four-plexes, and cottage courts — moderate-density housing types once common in American cities — are central to densification via urban infill.

Construction of these middle-density housing typologies has all but vanished: whereas roughly 7% of new housing construction in the mid-1980s was in buildings with 2-4 units, this share dropped to just 0.2% in 2021.

Allowing fine-grained increases in density within stable neighborhoods tends to be more politically feasible and cost-efficient — and less disruptive socially — versus full-scale upzoning or greenfield sprawl.

However, recent zoning reforms have struggled to revive this segment. Minneapolis’s 2019 elimination of single-family zoning, for instance, yielded few duplexes or triplexes because restrictive floor-area ratios and height caps made the math untenable. The lesson here is not that zoning reform fails, but that it must go beyond legal permission to include economic feasibility.

The missing middle can only return if cities pair regulatory liberalization with design flexibility and streamlined permitting. Additionally, the best policies on this segment should include the removal of minimum parking requirements so as to encourage housing construction and development along transit and commercial corridors.

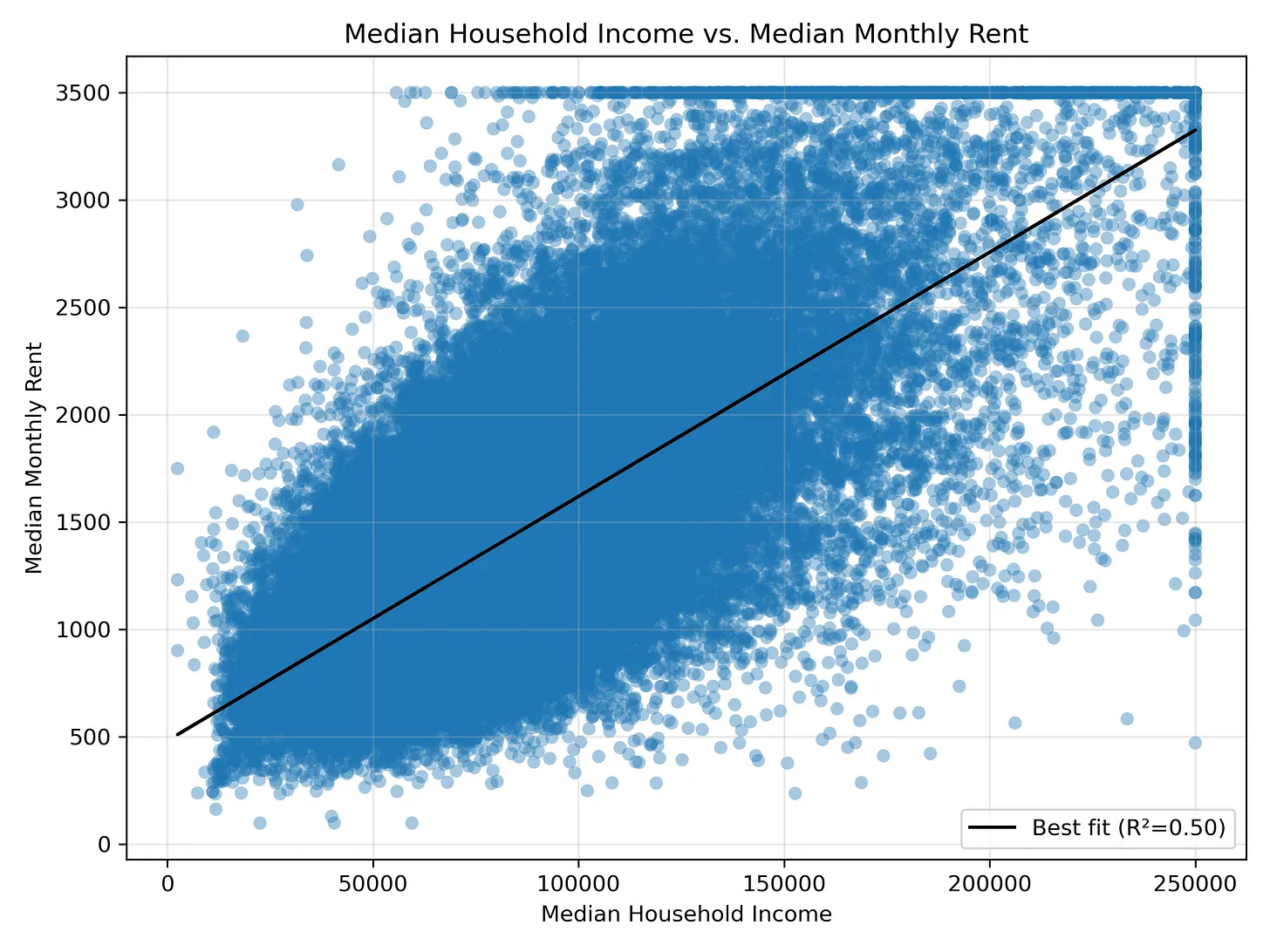

6) The primary determinant of housing costs in an area is income, but something might be off with the way we measure supply constraints (i.e., the “regulation tax”).

It sounds painfully obvious, but it is a fact that people rarely seem to discuss: higher incomes lead to excess housing demand, which puts upward pressure on prices.

There is variation geographically between how much of a household’s income is consumed by housing, but both within and between cities most variation between expensive and cheap housing can be explained by the demand component.

A recent San Francisco Fed working paper titled “Supply Constraints Do Not Explain House Price and Quantity Growth Across U.S. Cities” by Louie et al. takes this a step further to argue that most cities have very similar supply curves in practice. The study has been making moderate waves in the housing discourse. Their headline result that “relaxing regulatory housing supply constraints may not materially affect housing affordability” flies directly in the face of Econ 101 logic and the prevailing academic consensus — namely Gyourko & Molloy (2014), Glaeser & Gyourko (2018), and Glaeser & Gyourko (2025). Even if you do not accept this, an undeniable fact remains: in the housing market, the ability to pay is a first-order variable in cost.

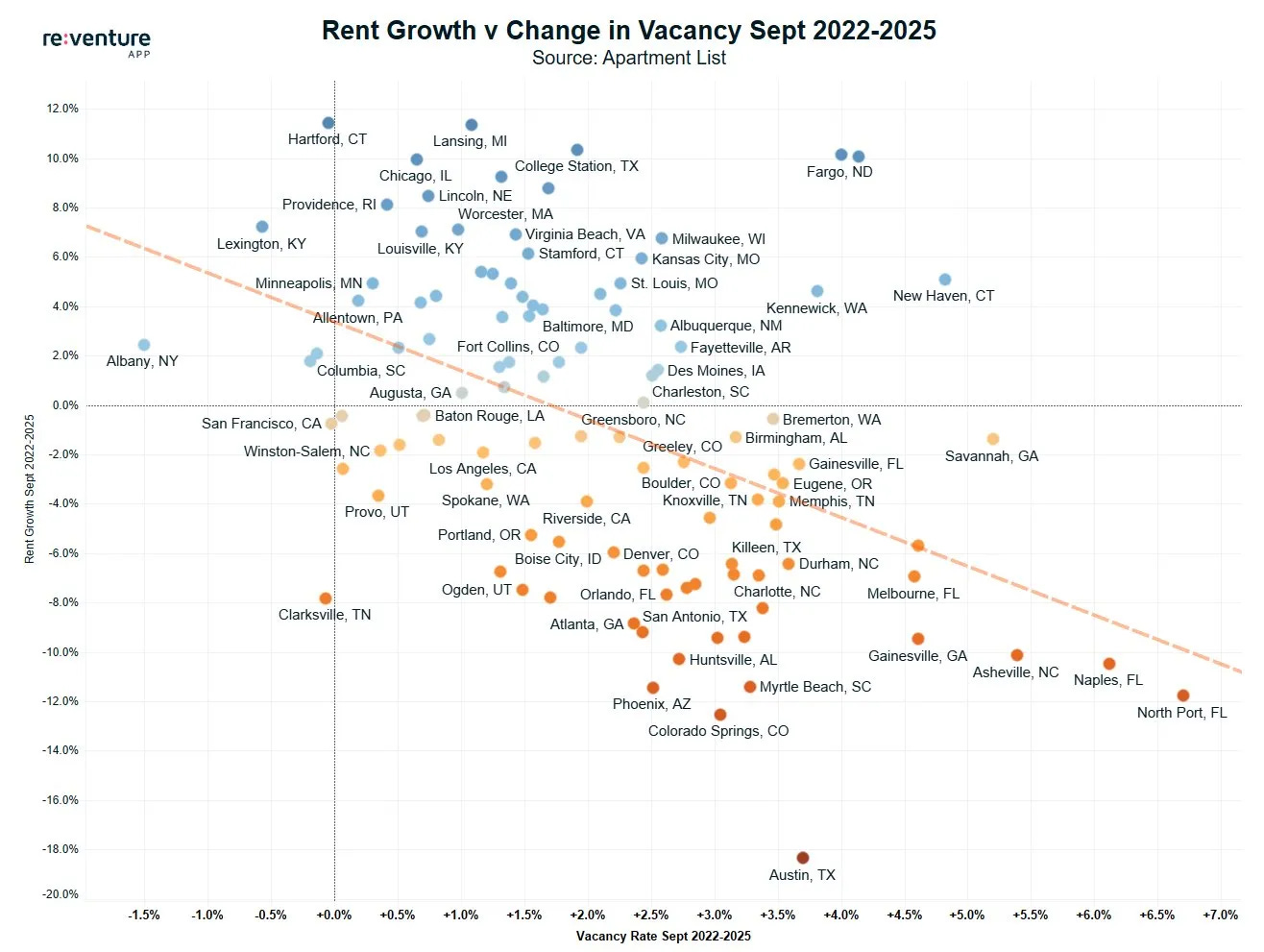

Nevertheless, it is still the case that all four major measures of supply elasticity traditionally used in academic research — Saiz 2010; Baum-Snow & Han 2024; WRLURI; Davis et al. 2021 land share — simply fail to explain (in a statistically significant way) the growth in housing stock given an increase in demand. This is also consistent with our takeaways from an analysis we did on where rents are falling:

Yes, there is evidence apartment rent growth is tied to vacancies;

Yes, there is some evidence construction rates are tied to vacancies;

No, given prevailing methods of measurement, there is not a clear link between local land-use regulatory regimes and levels of multifamily construction.

What we’re convinced this might mean is that current measures are failing to pick up the actual ground truth surrounding local supply constraints — and so there is enormous space for researchers to innovate (which Arpit Gupta is doing).

It is perhaps also true that hyperlocalism — activist opposition clustering around individual projects, which measures like WRLURI overlook — probably plays a decisive role in determining the true elasticity of housing, rather than just the explicit statutory law.

Let us know whether Louie et al. 2025 is right or wrong, or what you think these measures of regulation are failing to capture.

7) Vacancy drives rents lower.

In our recent article on where rents are falling, we examined what variables seem to be leading to a softening of rental costs in cities like Austin, and the most important variable appears to be vacancy.

This makes intuitive sense because higher vacancy rates imply that there is an oversupply of housing at the current price point, and so landlords have to lower costs in order for the market to clear. It does mean that rental price declines almost certainly mean significant pain for developers and landlords — thus a slowed pace of new construction.

8) Monetary policy can also play a crucial role in unlocking homeownership opportunities.

We explained the mortgage rate lock-in effect in this excerpt from our “Fed Pill”:

Benchmark 30-year mortgage rates plummeted from around 5 percent in 2010 to historic lows below 3 percent during the pandemic, fueling a speculative frenzy that saw home prices appreciate 40 percent nationally between 2020 and 2022. But the Fed’s subsequent quantitative (and otherwise) tightening — ushering in a rapid increase in mortgage rates, which have hovered in the 6-7% range since 2022 — created an even more pernicious dynamic: the mortgage lock-in effect where existing homeowners with sub-3 percent mortgages are rate-caged, unwilling to sell and lose their below-market financing.

This has frozen a significant quantity of existing home supply. Gerardi et al. (2025) found that not only are younger home buyers “disproportionately affected by mortgage lock‐in, which disrupts their typical pattern of moving to higher‐quality neighborhoods,” but that absent mortgage lock-in, a home’s time listed on the market “increases by 80–109%, house prices decline by 2–4%, and match surplus increases by 0–5%.”

The Fed could take targeted actions to alleviate the mortgage rate lock-in effect, and not just by lowering short term rates! It could instead:

Compress MBS spreads by 20-30 basis points simply by stopping the runoff of its $2+ trillion MBS portfolio, delivering a similar impact to that of a 100 basis point federal funds rate cut; or

Sell legacy MBS and reinvest the proceeds in current securities — an even more aggressive approach which could push mortgage rates down 40-50 basis points while shortening the Fed’s balance sheet duration.

Despite this, speaking on Tuesday at the National Association for Business Economics conference in Philadelphia, Fed Chair Powell definitively ruled out such interventions, stating: “We would certainly not engage in mortgage-backed security purchases as a way of addressing mortgage rates or housing directly. That’s not what we do.”

Powell and the Fed — perhaps ironically — view housing affordability as a structural issue requiring supply-side solutions (zoning reform, construction) rather than a monetary policy problem, despite the mortgage lock-in effect significantly constraining housing market function.

9) We’ve tried subsidizing demand every which way, but haven’t taken a serious stab at supply-side subsidies.

Federal and state governments have poured hundreds of billions, arguably trillions, into demand subsidies — via mortgage securitization, interest deductions, down payment assistance, low-rate credit subsidies, etc. — without fixing the fact that supply is quite unresponsive to demand in certain major markets.

These demand-side policies raise purchasing power for some but inflate prices for everyone else, transferring wealth from would-be buyers to incumbent owners. The result is a paradoxical “affordability trap” whereby policies designed to help households buy homes make homes less affordable.

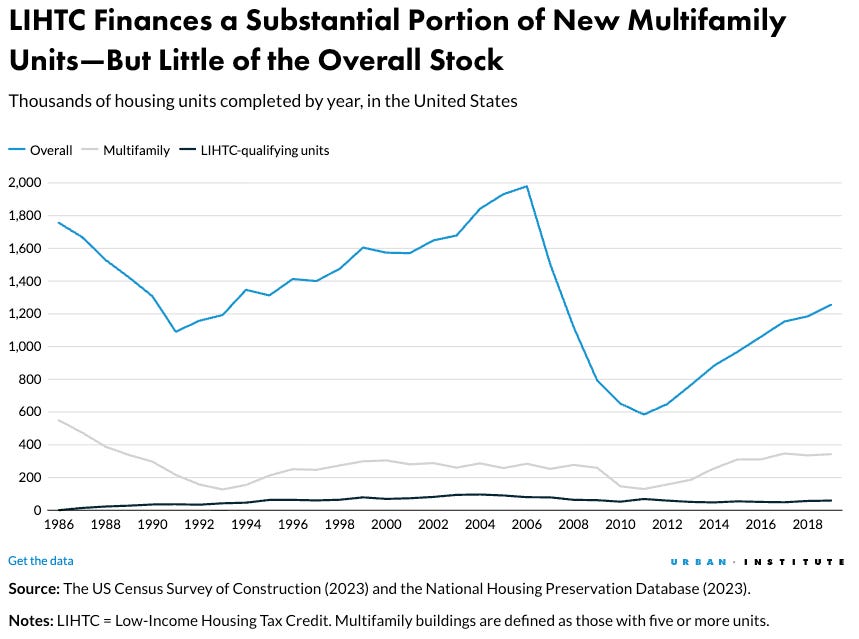

On the supply-side policy front, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC), while successful in creating nearly 3 million affordable units since inception, represents only 3-5% of all new housing construction nationally.

Furthermore, as previously explained, because of the filtering effect, it’s not just about building “affordable” housing. Supply-side interventions that lower per-unit costs — like targeted production incentives, infrastructure investments, and labor supply programs — for market-rate developers remain relatively underused.1

It should also be noted that supply constraints vary across different markets: in San Francisco or Boston, the binding constraint is regulation; in Phoenix or Austin, it’s infrastructure. This heterogeinity undoubtedly complicates things at the national policy level. A functional housing policy would calibrate to these local bottlenecks rather than pretending a one-size-fits-all program can solve a supply crisis that’s fundamentally heterogenous across metros.

The bottom line is that the input costs of homebuilders and developers are passed on to consumers of housing, and true affordability starts with targeting these costs and lowering them. Unless the policy equilibrium shifts toward production — e.g., streamlining permitting, incentivizing infill, smart financing of infrastructure — the next round of affordability measures will repeat the same errors. If the policy goal is greater access to housing, we don’t need more stimulus for buyers; we need capacity and runway for builders.

10) Property taxes quietly shape housing affordability and mobility.

Property taxes rarely make headlines, yet they are one of the most consequential — and misunderstood — drivers of housing dynamics. Counterintuitively, higher property taxes can actually increase housing affordability by functioning as “embedded leverage” that reduces required down payments through capitalization effects. Coven et al. (2024) showed that raising California’s property taxes from 0.8% to Texas’s 2% level would increase homeownership by six percentage points and young household ownership by eight percentage points.2

But when assessment limits or exemptions kick in (like California’s Proposition 13), the effect reverses. That is, older owners who are sitting on large property value appreciation gains face little incentive to sell, while newcomers bear disproportionate burdens.3

This effectively stymies mobility, freezes inventory, and entrenches generational inequality. Areas with higher property taxes feature more young homeowners, fewer empty bedrooms, and higher percentages of children in the population. Property taxation is thus not just a fiscal instrument but an under-the-radar policy lever that, if pulled intelligently, could unlock more active housing supply.

11) There is a shadow housing cost created by ethnic diversity.

One of the most consistent academic results with respect to the effect of immigration on housing is that on the neighborhood level the price effect which a classical economics model would anticipate from a population shock is muted because natives relocate away from the more diverse neighborhood.

Recently, Damm et al. (2025) observed this in Denmark by looking at a plausibly exogenous refugee resettlement program, but it is only one paper in a much larger literature. Saiz & Wachter (2011) showed a similar effect of immigration causing native flight in the US. This is also consistent with research like Schelling (1971), Clark (1991), and Cutler et al. (1999), each of which showed that people have a strong preference to live near their own coethnics.

It’s just true: as a country becomes more diverse, people’s desire for local homogeneity naturally increases, driving geographical segregation and thus limiting the set of possible neighborhoods homebuyers are willing to consider. And when an increasing number of buyers are vying for a limited subset of the housing stock, price distortions emerge.

Whether or not there are legitimate policy implications undergirding this effect on local housing markets remains to be seen.

12) Deporting illegal immigrants constrains housing supply.

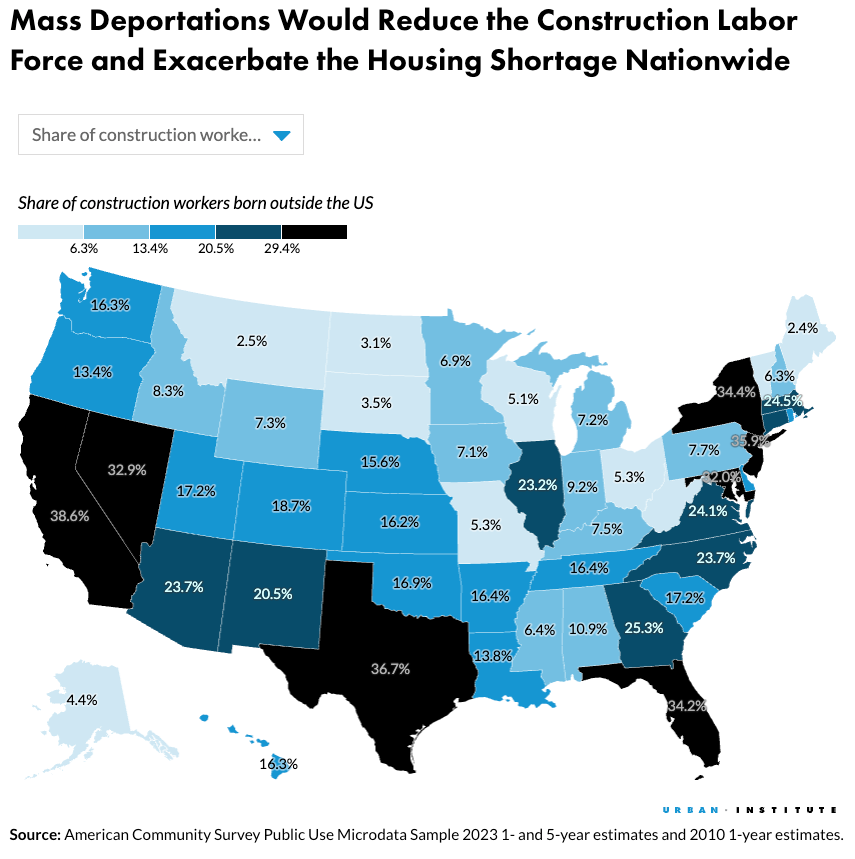

Immigration debates (like the above) often focus on demand — foreigners competing with natives for homes — but ignore the supply channel. The reality, on the other hand, is that immigrant labor constitutes a massive share of the construction workforce, particularly in trades like framing, roofing, and finishing.

The research supports this notion. Howard et al. (2024) leveraged an increase in immigration enforcement — arising from a federal program called Secure Communities (SC), which began in 2008 and eventually rolled out to all counties nationwide by 2013 — to study the impact of deportations on construction labor supply. The study’s findings revealed that:

“Treated counties experience large and persistent reductions in construction workforce, residential homebuilding, and increases in home prices.”

“Undocumented labor is a complement to domestic labor: deporting undocumented construction workers reduces labor supplied by domestic construction workers on both extensive and intensive margins.”

“Three years after Secure Communities rollout, the average county has foregone the equivalent of an entire year’s worth of additional residential construction: 2,423 fewer building permits and 1,997 fewer new construction transactions.”

It also found that demand-side downward pressure on prices from deportations is temporary and quickly dominated by supply-side impacts. But perhaps the most striking finding was a lack of any wage increases in the construction sector in the wake of deportations (thus lower supply of workers). In fact, the evidence strongly suggests that builders reduce output rather than increase wages.

Compounding this effect is the fact that, according to Urban Institute’s analysis, immigrants make up more than 23 percent of the construction workforce — and an estimated 54 percent of those foreign-born construction workers are undocumented. Deportations then could cause the US to lose between 1.7 and 1.8 million undocumented construction workers.

Indeed, removing undocumented workers causes a classic supply shock in construction — and the effects of mass deportations are likely to be unfolding in the US in real-time.

13) Crime and disorder are meaningful drivers of the extreme pockets of unaffordability we’ve seen develop in the US housing market.

When examining US housing affordability, crime avoidance has to be taken as a first-order consideration. As explained through the lens of our “Ghetto Pill”,

Detroit, St. Louis, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and others were once among the wealthiest cities in the world, but with the hollowing out of the manufacturing sector and subsequent explosion of crime in the middle of the 20th century this changed. Between 1950 and 2020 Detroit lost nearly 70% of its residents and fell from the 5th to the 27th largest U.S. city. In 2012, a third of its land—40 square miles—was vacant. St. Louis, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh each lost around half their populations, and even Chicago is down by a third. Vacancy in some neighborhoods exceeds 20–30%, compared to a 1.6% national average.

This dysfunction drives people who can afford to leave out. In addition to encouraging out-migration, disorder also causes communities to put up barriers to new development for fear of filtering in the “wrong type of person.” In a survey of developers in New York state, for example, crime was by far the most often listed concern.

Often these effects show up at the neighborhood rather than the city level, meaning that most people aren’t pushed out of a metropolitan area as a result of crime but instead relocate to different parts of the city. As a result, the actual correlation between crime and housing prices is negative — the most dangerous areas are also the cheapest — but this is a result of crime crushing demand in certain communities, which in turn drives up prices in the suburbs. It is this pattern of within-metropolitan relocation which leads to the consistent pattern across this country, but most notably in the Midwest, of depressed urban areas surrounded by very expensive suburbs.

14) People living longer has permanently changed the housing market.

The rise in average life expectancies has its drawbacks. Quoting from the “Boomer Pill”:

The Baby Boomers are now in their 60s, 70s, and early 80s and control the plurality of housing wealth—over 40% of all real estate assets. … From July 2023 to June 2024, Boomers comprised 42% of all home purchases compared to only 29% for people between the ages of 26 and 44. This is a radical departure from the late 20th century—for example, in 1981, when the median age of a person buying a house was just 31 years old.

One of the most significant changes in the postwar era has been the international explosion in life expectancy; it is now considered totally normal to live well into your 80s. Although this is obviously good, it has also resulted in a permanent structural change to the housing market since elderly Americans are holding onto their homes for longer and longer.

How this will shake out in the long run, or what government policies, if any, will exist to incentivize downsizing for retired citizens, is unclear — but it is an enormous change relative to the past.

15) A lot of people live in homes that couldn’t legally be built today.

A recent audit of Boston’s housing showed that only 1% of residential buildings would be able to be built under current zoning laws. This is consistent with results from NYC where similarly the overwhelming majority of current housing fails to live up to regulatory standards. As a result people are locked in vastly inferior housing to what could currently be built and these cities have sacrificed the “good” at the altar of the perfect. By raising the regulatory threshold so high no new building can occur the only effect is keep people from being able to live in new updated apartments.

Conclusion:

We hope that you have found our dive into the messy details on housing as interesting as we did. Our goal in this first phase was to strip away as much of the noise as possible and ground ourselves in what’s empirically true. The next step is harder but more important — figuring out what to do about it. Over the coming weeks, we’ll start sketching our bold asymmetric solutions and we invite you to participate in this process with us by submitting your solution to our essay contest.

Submissions close October 31st and the top prize is $2,500! More in the linked article below:

Recent research shows tax-based incentives for market-rate housing construction generate strong returns on investment for municipalities through increased tax revenue and economic activity, yet adoption remains limited compared to demand-side programs.

The mechanism is relatively straightforward: higher expected property taxes get capitalized into lower home prices today, with cross-sectional estimates implying a discount rate of around 4.5%

Shan (2008): Subsequent amendments (Propositions 60 and 90) that allowed homeowners 55+ to transfer their tax base when moving produced sharp discontinuities in mobility, confirming the causal impact of property tax lock-in.

8. The Fed printing money and buying $2T of MBSs is a fake market. Wealthiest business entity on the planet and gets to print money to buy its friends' stuff. Freedom to fail is for the schleps.

12. If deporting illegal immigrants would put such a dent in the trades that it would constrain housing supply, then you have just uncovered a RACKET of capital against labor. The advantage goes to sleazy and unsophisticated operators who are indifferent to things like payroll taxes and comp premiums.

Regarding #5, the reason so few small multifamily units are built these days is cultural: they have become "low class".

Upper-class people can live in apartments, if only as stepping stones to owning nice homes, but owning in a row house is out of the question for most self-respecting people. I'm not saying that this makes sense; only that it is true.