8 More Housing "Ground Truths"

On financialization, cap rates, market frictions, whether there's a crisis, supply constraints, YIMBYism, spatial misallocations, and human capital densification

Throughout our housing sprint, we have dug into the logical frameworks supporting competing narratives and squared those against a large body of academic research and empirical evidence in hopes of establishing a set of “ground truths,” or a set of baseline facts and premises that should be foundational to sound policy recommendations.

We shared fifteen of these “ground truths” in a previous post, which had a lot of good feedback. Today we’d like to share eight more that have been informative to our “house view” on… housing.

1) The “financialization” of housing is a pillar of economic freedom.

Housing-as-an-asset is one of the great inventions of liberalism. In any economically free system, a house and the land underneath it inevitably becomes both a place to live and a store of value. Treating housing as an asset is simply what happens in a society with secure property rights — where ownership is protected and exchange is free.

History backs this up and provides context on the “financialization” part. Mortgage finance and even early forms of securitization existed more than a century ago. Colonists turned land into money — collateral, circulating credit, tradeable title — because marketable property made opportunity portable.1

It is tempting to frame this all as financial decadence, as one of the many pathologies of late-stage capitalism. But compare it to autocracies, where land so often becomes a political instrument and a tool for consolidating power. Those systems redistribute arbitrarily because they lack what markets provide automatically: decentralized allocation of risk and capital.

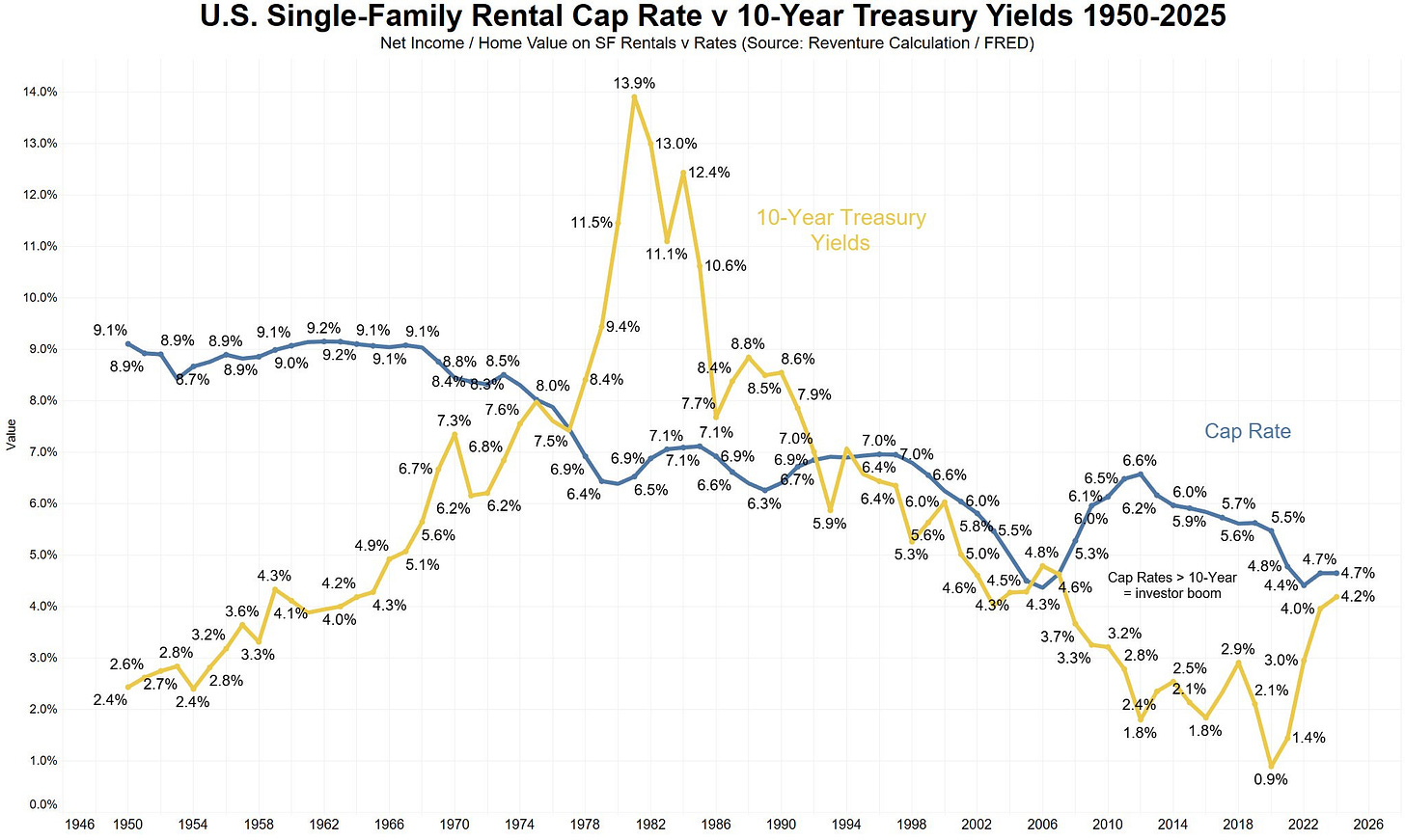

Critics often say homes should be “just shelter” and not yield-bearing assets, arguing that the “asset” frame breeds speculation and rentier excess. This logic runs backwards. Asset values and rental yields are the information system that signals when builders should build, and where. When rental yields rise, it signals scarcity; when they fall, it signals abundance. Remove that signal and you get one of two models: a state monopoly on rental housing or private landlords operating as philanthropists. Neither is very feasible for housing a population at scale.

Thus the “financialization” of housing is not just a way for investors to make money — it is a way for scarce resources to be allocated efficiently. Absent “financialization,” we are stuck with centrally-planned markets, and history has not been kind to such regimes.

2) Housing prices adjust to rents, not the reverse.

Asset values across all markets — stocks, bonds, etc. — are determined by the value of expected future cash flows, discounted to the present.2 In real estate, those cash flows take the form of rental income (for investment properties) or imputed rent (for owner-occupied dwellings).3

The fundamental equation of real estate finance is the following: property value equals annual net operating income divided by the capitalization (cap) rate. Therefore the formula for calculating the cap rate itself is:

This formula is an inescapable consequence of capital theory and the law of arbitrage4; the cap rate functions as both a yield measure and a discount rate in stable, non-growing scenarios — it bridges current income yields and expected returns. Consider fixed income (bond) investing as a comparison. There are two distinct scenarios where a bond investor would be compelled to allocate capital to, say, 10-year Treasuries:

They expect Treasury yields to fall (via price appreciation); or

They view the current yield (income generation via coupon payments) attractive relative to risk.5

The allocation decision, then, turns on expected returns, not past price movement. Similarly for the real estate investor, their capital flows to where:

They expect cap rates to fall (via price appreciation); or

Current cap rates are attractive on a risk-adjusted basis.

Notice that (perhaps counterintuitively) investors in either market look for falling yields and falling cap rates. But where real estate diverges from bonds — and why this matters for housing — is in the numerator (NOI for real estate and coupon for bonds). Income from a bond is contractually fixed. When interest rates rise, your coupon is locked in; you are stuck with it. Rents — or, more precisely, NOI — are different from coupon payments. They can rise or fall based on fluctuating demand for housing. This flexibility is paramount to real estate valuations.

Now, the framing that “rents follow prices” gets the causality backwards — it is a bit like saying that a stock’s price (or market cap) determines the underlying company’s earnings. Sure, when a firm is flush with equity value it may tap that equity to raise new capital in pursuit of new growth opportunities. But it is well-studied: stock prices follow the stock’s earnings — and blatant (sometimes, in hindsight, irrational) misvaluations seldom persist over the medium-to-long run.

Similarly, in a rational, well-functioning housing market, rents reflect the true demand for housing services while prices merely capitalize that demand. When a developer builds an apartment and can rent it for $2k/month, a 5% cap rate implies a unit value of $480k — mechanically, not optionally. This relationship holds because investors compare real estate returns to alternatives. If they can earn 5% from rental income on real estate or the same 5% from Treasury bonds, the latter looks far more attractive. However, if cap rates offer a premium for the risks of investing in real estate — capital-intensity, cyclicality, illiquidity, etc. — capital redeploys up the risk ladder.

This is all to say that investors allocate capital on the basis of risk-adjusted returns. Real estate values — indeed, all risky assets — are acutely sensitive to interest rates. When the “risk-free rate” rises from 2% to 4%, investors demand higher yields (cap rates) from risky assets (real estate). And when cap rates rise, property values fall given a fixed rent stream. This math is relentless.

So it isn not the case that housing production simply responds to higher prices. A construction project works if and only if the rental income — on a net operating basis, not just headline rents — justifies the developer’s required return.

Policy wonks would do well to view housing production through this IRR (internal rate of return) lens: is the net present value positive? Prices do not answer that question or determine whether a deal should pencil out. Cash flows — rents minus landlord expenses — do. Robust expected growth in these cash flows is just as important. (h/t Mike Fellman, who writes about this frequently).6

In short, rent growth is required to induce new housing production. This explains why policy interventions that suppress rents (rent control, inclusionary zoning) or artificially depress cap rates (QE, mortgage subsidies) produce chronic underbuilding. Rents should reflect demand for housing services. Prices capitalize that demand until cap rates normalize again. Break the rent-to-price relationship, and you break housing production.

3) The US housing market is not in a well-functioning equilibrium.

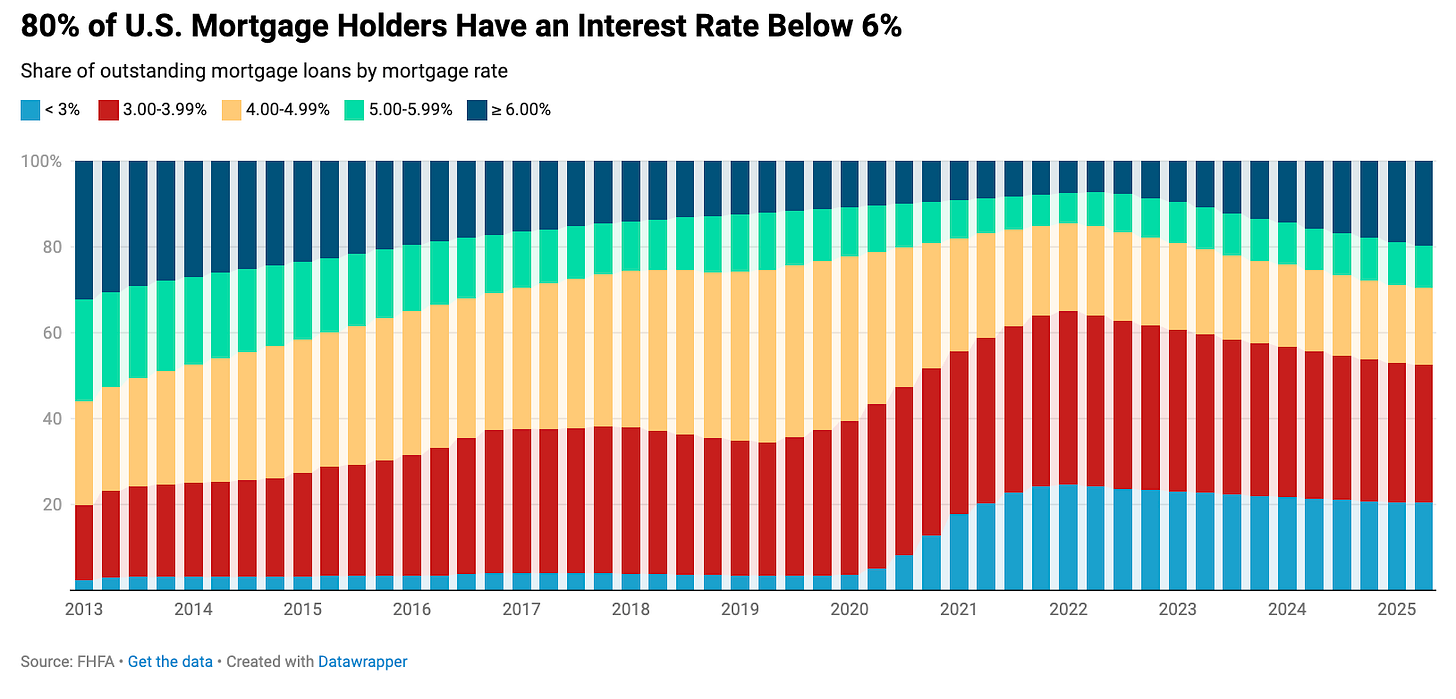

The “mortgage lock‑in” or “golden handcuffs” effect is now a defining feature of the market: just over half of mortgaged homeowners still carry rates below 4%, and more than 80% are still below 6%.

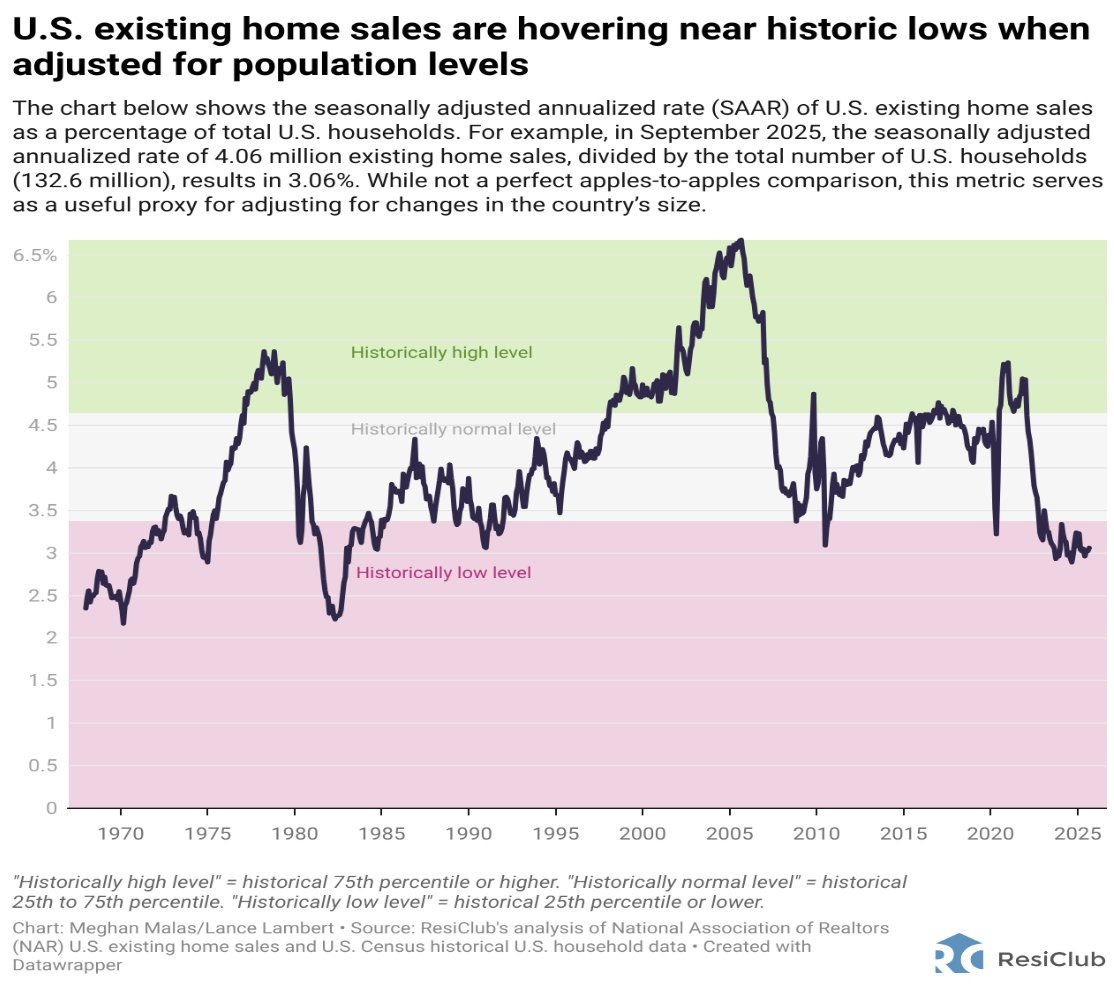

With new mortgages pricing in the mid‑6s, the cost of trading up or moving sideways is prohibitive, so existing‑home sales and overall transaction volumes have fallen to multi‑year lows even as national home prices have been roughly flat or slightly rising. Homes linger on market 5–7 days longer than a year ago yet prices remain sticky. This is not a healthy, well‑cleared equilibrium; it is a low‑mobility, high‑price regime where stalled existing home sales have rendered price discovery impaired:

It is well documented that homebuyer demand is waning and even anemic in some markets. In a frictionless market — where the opportunity cost of abandoning low-rate mortgages did not prohibit many homeowners to sell and move based on their housing utility function7 — the combination of weaker demand and 6%‑plus mortgage rates would translate into lower prices.

Instead, high accumulated equity and cheap legacy debt allow many owners to simply refuse the new equilibrium: when bids come in below their psychologically anchored list prices and 2022-nostalgic valuations, they either wait, cut minimally, or delist altogether (or even “rage delist”) — anything besides accepting sale prices.8

The reality is that housing is already structurally a high‑friction asset — large transaction costs, slow search, and significant information asymmetries between buyers and sellers — and that these structrual frictions are now amplified by mortgage lock‑in, high equity cushions, and sticky nominal anchors.

In other words, effective bid‑ask spreads in the housing market have widened, suppressing price discovery. Buyers’ reservation prices are compressed by higher rates and affordability constraints, while sellers remain anchored to post‑Covid peak valuations and Zestimates. Instead of converging through robust price discovery, the market is freezing around a price level that is likely higher than the one a more fluid, lower‑friction market with the same fundamentals would produce.

4) Whether or not there is a national “housing crisis” is in the eye of the beholder.

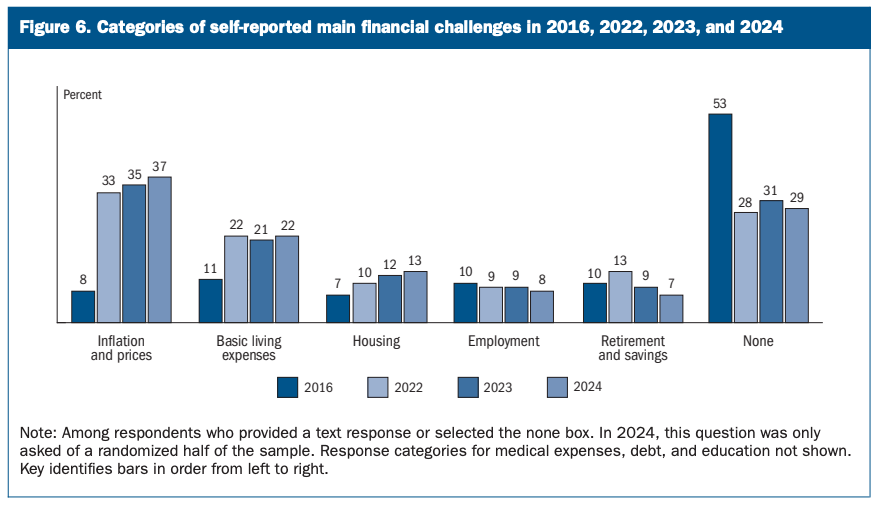

“Affordability” has supplanted “abundance” as the causa celebre. Ezra Klein cannot go five minutes without saying it. Trump thinks it is a “radical left-wing” psyop (lol). In any case, it is politically salient, and housing is high on the “affordability” totem pole.

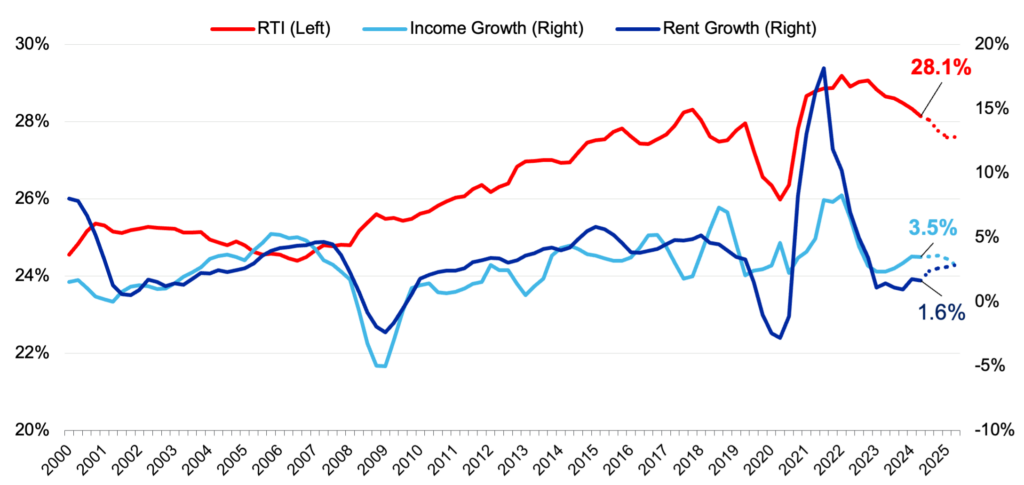

Affordability in housing cannot be adequately measured by rent-to-income (RTI) ratios alone because these ratios remain remarkably stable across different geographies and time periods due to compensatory behaviors by households.

Housing sits in the middle of the consumption spectrum — neither a luxury good (like watches) where spending increases faster than income, nor an inferior good (like food — see: Engel’s law) where fractional spending declines with wealth. This makes rent-to-income ratios an unstable foundation for quantifying affordability or assessing whether we are in a crisis.

When incomes double, housing spending typically increases by 65–70%, not proportionally with income. People do respond to income increases by demanding more bedrooms and space, but housing demand grows sub-proportionally to income gains. In econ-speak, this means that housing demand is “income inelastic”9 with an elasticity around 0.67 (Albouy and Ehrlich 2016). As a consequence, the share of income spent on housing falls as incomes rise — a relationship known as Schwabe’s Law10, documented since the 19th century.

Moreover, when housing becomes too unaffordable in a particular area, people move, which means local affordability statistics mask the true constraint because households have already made compensatory adjustments. The apparent “lack of unaffordability”11 in the data actually reflects that people have been priced out and they have likely relocated.

A superior definition of housing “affordability” asks: Can people live where they want? Can they access housing typologies they prefer in a given market? Can they reach job markets offering the best returns? Can they access desired amenities like good schools, parks, and nature?

Higher real wages, lower basic living expenses, and the easing of broader cost pressures could just as plausibly deliver affirmative answers to these questions, without any improvement in housing affordability at all.

In fact, something like high healthcare costs cannot really be avoided by relocating whereas people can and do sort, geographically, into the housing markets that fit their budget constraints. Nevertheless, this gets at the notion of “spatial misallocations,” which we will discuss a few sections later (section 7). But first, we need to touch on the key supply-side debates in housing.

5) Relaxing supply constraints is not a panacea, but it is also not nothing.

The Louie-Mondrago-Weiland (LMW) study has ruffled some feathers among purveyors of the housing supply-side orthodoxy (see: Glaeser Pill). It showed, very basically and even intuitively, that the established measures of zoning rules and land use restrictions — “supply constraints” — do not actually explain house price and quantity growth across US cities. That is, in econ-speak, that supply elasticities — or the responsiveness of growth in housing supply quantity to changes in price — do not meaningfully differ from one city to the next.

Contrary to the consensus view, the paper instead finds that higher income growth predicts the same growth in house prices, housing quantity, and population regardless of a city’s estimated housing supply elasticity. In other words, LMW finds that on a city-by-city basis, supply responds to demand in a similar fashion.

This comes at a time when the Glaeser-Gyourko-Saiz camp, which has rallied housing policy advocates and grown in influence over multiple decades, has reached a crescendo. Endorsed by the 2024 Economic Report of the President, the YIMBY movement, the “Abundance” agenda, and countless housing policy advocates, the prevailing thinking rests on the premise that where it is harder to build (due to geography or regulation), supply is less responsive to price increases, so prices rise more for the same demand shock. Regulatory costs account for roughly 25% of single-family home prices and 40% of multifamily costs, the standard thinking goes.

The policy prescriptions downstream of this supply-side consensus view flow logically: remove regulatory constraints, increase supply elasticity, restore the price-quantity tradeoff, and solve affordability. But if LMW’s findings are accurate and robust — that measured constraints do not predict differential market responses — the linchpin of the supply-side consensus fails. Indeed it would suggest either that genuine elasticity differences across cities are negligible, or that existing measures genuinely fail to capture the differences.

6) So, is Abundance bullshit and the YIMBY movement all for naught?

Not quite. Some argue that land use regulations do not meaningfully constrain building, but there is strong evidence of its distortionary effects — evidence that withstands the LMW’s findings!

Namely, Baum-Snow-Han (2024) found that intra-city elasticity is still highly heterogeneous, showing a range of 0.2-0.9 across tracts12 — highest in peripheries, lowest in central areas and high-value neighborhoods. This suggests that elasticity differences do not systematically sort across cities. Rather, within every city, elasticity varies sharply by location.

In other words, demand for housing is quenched at the city level as housing does in fact get built; but this development happens — elastically — in the peripheries and low-constraint areas while it is suppressed in high-constraint, inelastic areas. This is why LMW’s approach (looking at the metro-level price-quantity covariance) can show no elasticity gradient while at the same time, differing micro-elasticities may genuinely exist.

Does this mean that lifting supply constraints can unlock housing affordability? It is unclear, but probably not on its own — evidence suggests no systematic relationship. And in certain cases, relaxing constraints without affordability protections could even accelerate gentrification and displacement if development concentrates in vulnerable neighborhoods. So, in reconciling the opposing schools of thought, we can make the distinction that some “regulation tax” exists, though it does not necessarily operating as an “affordability tax.”

But what can be maintained is that zoning constraints produce negative externalities — forcing development into suboptimal locations, concentrating poverty in peripheries, reducing access to opportunity — that result in localized choke points. Empirical work supports the idea that cities function as networks of submarkets. Reform efforts should focus on the submarkets home to these choke points rather than assuming a one-size-fits-all elasticity.

So the academic evidence is mixed but informative. We know that restrictive local zoning can make housing scarce and raise prices in high-demand areas. We also know that adding supply tends to lower rents regionally. What remains debated is how big these effects are and how they play out spatially.

Herein lies the concept of spatial misallocation — the idea that housing is built to accommodate aggregate demand, but incongruently so. In other words, it is built in the wrong places and at suboptimal densities and orientations relative to amenities, jobs, transit lines, etc.

7) What even are “spatial misallocations”?

As we see it, this concept fundamentally represents the proverbial worker stuck in a mid-tier city who would be more productive in “superstar” cities but are priced out — and forced to sort into lower-productivity metros instead.

“Spatial misallocations” can sound a bit woo-woo — it describes micro frictions that are hard to see, and the causal chain is long and counterfactual. When someone says “I just don’t want to live there,” it sounds like tastes/preferences, not distortion. The economist Cameron Murray dismissed it outright in our live interview with him. But it is a fundamental inefficiency in housing economics with strong empirical backing. And it reconciles the LMW findings with the genuine distortions that zoning creates.

The productivity costs of these distortions have been shown to be substantial. Hsieh and Moretti (2019) found that housing constraints in high-productivity cities like New York and San Francisco reduced aggregate US GDP growth by 36–50% from 1964–2009. But this paper has become increasingly controversial so our arguments shouldn’t rest on its findings.13

Instead, recall from the previous section the findings of Baum-Snow-Han (2024) — that supply elasticity varies 0.2–0.9 within cities, creating localized choke points — and consider the geography of restrictive zoning. Single-family zoning clusters in high-amenity suburbs and established neighborhoods. Minimum lot sizes bunch where land is most expensive and demand is strongest. Height and density limits are most stringent near job centers and transit hubs — precisely where housing is most constrained. Essentially, a city accommodates aggregate demand elastically — housing does get built — but development concentrates where it’s legally easiest, not where it’s economically optimal.

The real catch here is that spatial misallocations become locked in. Rollet’s (2025) research on urban redevelopment finds that redevelopment faces large fixed costs that rise sharply with the size of buildings being demolished. Once housing is built in suboptimal locations, the opportunity cost of later redevelopment to achieve efficient land use allocation becomes prohibitively expensive. Zoning constraints amplify this by forcing initial development into the wrong places, ensuring that spatial misallocation persists long after policy might theoretically change.

Ironically, this is unfortunate news for both YIMBYs and NIMBYs as it creates a trap: neither reform nor inaction solves the misallocation problem on a politically relevant timeline.14

So, relaxing constraints wouldn’t necessarily lower prices (LMW’s point), but it could potentially increase economic efficiency by allowing better spatial matching of workers to high-wage labor markets. What, then, does this say about densification? Should we unambiguously aim to build more and build higher in urban cores?

8) Densification, in and of itself, should not be a policy goal.

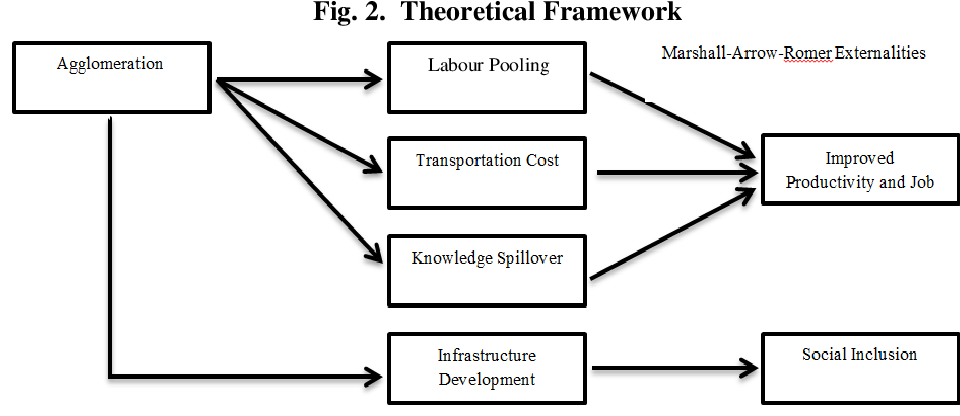

Undergirding densification are deep (socio)economic forces: the effects of agglomeration and human capital clustering.

These forces are invoked to justify housing development policies, yet the empirical record reveals their gains are highly contingent and unevenly distributed. Glaeser and Resseger (2009) demonstrate that agglomeration economies — productivity gains from city size — are concentrated exclusively in high-skill metropolitan areas.15

More broadly, research commissioned by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York — Abel et al. (2011) — found no aggregate correlation between density and productivity, suggesting that agglomeration benefits are far from universal across metropolitan areas. When they dug down into the data, it became clear that, while for lots of industries there were no obvious agglomeration economies, for some the gains were very large. And these industries — finance, arts & entertainment, professional services and information — are the industries we most associate with successful dense urban places.

The implications are direct: densifying the wrong human-capital mix yields minimal welfare gains. Numerous studies have more recently corroborated these findings and expanded upon them:

A 2020 Upjohn Institute review found that a 10% increase in density is associated with a 0.4–0.8% increase in productivity, but that elasticity can double in high–human capital metros.

Baum-Snow et al. (2013) found that metropolitan areas with human capital one standard deviation below the mean realize essentially NO productivity gain from doubling density (actually -1.0%), while high-human-capital metros see gains about twice the average (5.3% vs 2.6%).

Rattanakhamfu et al. (2024) showed that in Thailand skilled workers gained 15.2% wage increases from density while unskilled workers gained only 1.8%.

Even setting the nuance aside, the fact that the economic performance of places does not map cleanly onto levels of urban density is vindicating. Densification, then, is not quite the silver bullet that city boosters and YIMBYs argue; indeed, what matters more is the gross size of the metropolitan area rather than the metro’s density:

“The shape of the city in space, including for example its residential density, matter much less than (and are mostly accounted for by) population size in predicting indicators of urban performance. Said more explicitly, whether a city looks more like New York or Boston or instead like Los Angeles or Atlanta has a vanishing effect in predicting its socio-economic performance.”

Finally there is a separate, underappreciated dimension to densification in low-human-capital tracts: concentrated disadvantage and crime. Research on neighborhood effects consistently shows that concentrated poverty, social disorganization, and weak collective efficacy generate higher crime rates — and that these effects are amplified by density.16

Put differently and in short, positive agglomeration effects are tied to human capital composition, not spatial intensity. Densification housing policies that ignore this asymmetry in favor of subsidizing low-human-capital in otherwise productive areas (because muh “displacement”) risk not only lower productivity but devolving social order.

Thanks for reading. We are excited to be wrapping up our housing sprint, and over the next couple weeks we will be featuring the top submissions from our essay contest!

Please do subscribe if you haven’t already.👇

Quoting a recent piece by Ed Glaeser in the WSJ, where he reviewed Mike Bird’s book, The Land Trap: A New History of the World’s Oldest Asset:

Mr. Bird begins in colonial America, where the English colonists realized that their new societies “would be defined by an enormous wealth in land” and attempted to “turn land into money” through land-based credit or land-based currency. The Debt Recovery Act of 1732, we are told, formalized the “ability of creditors to foreclose on American land”; without it, lending on land would have been almost impossible. Mr. Bird cites Claire Priest’s excellent “Credit Nation: Property Laws and Institutions in Early America” (2021), the book to read on colonial financial institutions.

Yields on short-term Treasuries (T-bills) are used as a proxy for the discount or “risk-free” rate.

For an owner-occupied unit, most of the cost of shelter is the implicit rent that owner occupants would have to pay if they were renting their homes, without furnishings or utilities.

Arbitrage dictates that capital flows to the highest risk-adjusted return, enforcing equilibrium. If housing yields exceed comparable financial assets, investors will purchase property until prices rise — and yields fall — sufficiently to eliminate the disparity. This mechanism binds real estate values to the broader cost of capital.

The predominant risk to the long-term fixed income investor is inflation

Additionally, future growth in cash flows become necessary to offset high financing costs, as discounting future cash flows to the present using higher rates lowers NPV.

This is equally true for mortgage-less homeowners (100% equity) — they see high prevailing prices elsewhere and high financing costs as prohibitive as well.

As of November 2025 delistings were up about 45.5% YTD and 37.9% YoY, making 2025 the highest delisting year since Realtor.com began tracking the metric in 2022. The marginal transactions that do occur are thin, segmented, and skewed toward more motivated sellers, particularly in the $350–500k range where nearly one‑fifth of listings have required price reductions. (Source)

Unit-elastic demand (Cobb-Douglas preferences) has been the default assumption in many housing models simply for mathematical convenience, not because evidence supports it.

Schwabe’s law is similar to the far better known Engel’s law. It describes a negative correlation between household income and the share of consumption expenditures devoted to housing.

Via Cameron Murray in our live interview with him:

When prices rise they don’t everyone’s income doesn’t just go up 50%... some households income goes up 90% or 150% and some goes up 10% or 15%... if your income hasn’t increased as much as the average you’re going to get squeezed out of your suburb... it’s only unaffordable for you because it’s more affordable for someone else... we are perceiving that as a housing crisis because some people are being left behind.

An elasticity of 0 is perfectly inelastic; an elasticity of 1 is “unit” elastic; an elasticity of ∞ (infinity) is perfectly elastic, where any price increase causes quantity demanded to drop to zero instantly.

Critiques include:

Methodological issues: Brian Greaney (University of Washington) found coding errors and a theoretical flaw in the model’s scale dependency. When corrected, the model predicts near-zero GDP gains (0.02%) from deregulation — contradicting the headline 36–50% claim.

Kevin Erdmann’s fundamental critique is more damaging: The paper conflates housing obstruction (a pure transfer from renters to owners) with productivity differences. Using a thought experiment, Erdmann shows that housing restrictions can generate observed wage dispersal without any productivity differences at all — making agglomeration the secondary issue, not the primary one.

Selection bias in agglomeration economies: As Market Urbanism notes, SF and NYC attract especially productive, high-skilled people. But this doesn’t mean the next worker moving there gains the same productivity premium. Two-thirds of observed wage variation across metros is explained by skill-based sorting, not location itself.

Arpit Gupta brought the 2025 paper, “Zoning and the Dynamics of Urban Redevelopment” by MIT’s Vincent Rollet to our attention last week, and we found it to be important in that it fundamentally challenges the assumption that zoning reform alone can unlock housing supply, given that urban redevelopment faces structural economic constraints. It shows that the neighborhoods with the infrastructure, transit access, and urban form that are most suitable for “missing middle” housing cannot produce more of it merely through market mechanisms.

On the one hand, this would be bearish for the prospects of a comeback of the missing middle — duplexes, four-plexes, cottage courts, or moderate-density typologies once common in American cities — but only insofar as its comeback entails solely urban infill.

On the other hand, the study finds that zoning is the primary constraint in high-priced, low-density NYC neighborhoods like Western Brooklyn and Northern Queens. These areas — expensive single-family neighborhoods with good amenities — would see 39% of all additional floorspace from citywide upzoning despite representing only 10% of upzoned land. This is precisely where the “missing middle” can actually be built. But, evidently, because of exclusionary zoning, it hasn’t been.

Furthermore, Rollet (2025) finds that time horizons matter enormously — the benefits of zoning reform accumulate over 40+ years, meaning today’s reforms primarily benefit future residents rather than current ones.

For NIMBYs, it demolishes their argument that “redevelopment never happens anyway, so zoning doesn’t matter.” Rollet shows redevelopment is economically constrained, but not because it’s impossible—it’s because the opportunity cost is high. This means that where initial development happens genuinely matters, because it locks in spatial patterns for decades. You can’t just ignore zoning and assume market forces will sort it out later; the initial misallocation becomes entrenched.

So NIMBYs can’t hide behind “market forces will correct this eventually.” The locked-in misallocation is a feature of their restrictive zoning, not a market failure that will auto-correct.

Additionally, in metros with the lowest education levels, city size shows virtually no correlation with productivity; in high-skill metros, productivity gains accrue primarily to already-skilled workers through accelerated skill accumulation and innovation dynamics.

Glaeser and Resseger (2009) found that areas with above-average disadvantage and high-density housing show much higher incidences of violent crime than low-density disadvantaged areas, with an apparent nonlinear relationship suggesting that violent crime accelerates as density increases in poor neighborhoods.

Social disorganization theory explains this mechanism: high-density poverty concentrations erode informal social control and institutional capacity for crime prevention, while simultaneously increasing the density of criminogenic opportunities and social disorder. This stands in stark contrast to the productivity dynamics in high-skill metros, where density amplifies knowledge spillovers. In low-skill, high-poverty areas, density amplifies social breakdown.

This is a good overview. I think the inter city heterogeneity is important and also mmmmm not solvable. In the only market I care about (my own) you see big fights about rezoning apartment districts to high rise and ag to urban that create the impression we’re at capacity, but we actually have room for around 200k units in a mix of apartment, duplex, and single family homes, and a very straightforward process to get highrise zoning in exchange for some affordable housing in the urban core that comes with low interest loans. It’s just….developers don’t want to build there and that. Maybe for good reason idk, maybe just cause ag land is cheap and land costs are huge here.

It seems to me that home ownership as “wealth-building”, as opposed to simply having a place to live, may be a detriment to the economy and a source of unproductive and unjustified inequality.

The house (or, more accurately, the land under the house) that my wife and I purchased many years ago has insanely appreciated. Great for us! But has anyone else benefited?

A similar gain in the stock market would, at least in theory, have been our reward for providing investment capital to create new products, services and jobs. But land value is a zero sum game. My gain is at the expense of someone else who is struggling to pay the rent or the mortgage.

Yes, land values are important signals for the market allocation of land, preferrable to the inherently limited efficacy of central planning. I think the answer lies in “Georgist” thought, the implementation of a Land Value Tax, preferably as a replacement for income and sales taxes.