Why Fannie & Freddie should not be IPO'd

An alternative, hybrid approach to privatizing the GSEs

FHFA’s request for input

Since Trump’s election last November, the most debated topic in housing finance is whether — and when and how — his administration should move to take Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (F&F) out of conservatorship, which they have been in since 2008. An interesting element to this debate is that a conservatorship exit could be pulled off through either legislative or administrative means. But Congress has not focused on this (or any type of reform) in nearly a decade.

Now, under Bill Pulte’s leadership within the Trump administration, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), which regulates the 11 Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBs) as well as Fannie and Freddie — the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) collectively providing more than $8.5 trillion in funding for the US mortgage markets and financial institutions — is requesting input on a new strategic plan:

This comes as President Trump continues to call on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to get big homebuilders “going” while posting on Truth Social a logo of sorts reading “The Great American Mortgage Corporation”.

Meanwhile, FHFA director Pulte himself is hitting the podcast circuit, touting the prospects of an initial public offering (IPO). Given this momentum — and given the current administration’s inclination toward unilaterally circumventing legislative processes — we are rushing to propose a balanced, comprehensive plan for ushering in a post-conservatorship era for the GSEs via administrative means. Namely, in this article, we argue the following:

The GSEs remain systemically important to the US housing market, broader financial markets and real economy.

Conservatorship of F&F was never meant to be a permanent solution, and is an unsustainable format.

A traditional, pure-play IPO as the GSE conservatorship off-ramp would be a mistake that harms markets, taxpayers, homebuyers, and regulators alike.

A hybrid structure — via “mutualization” paired with a “golden share” conversion of Treasury’s shares and warrants — is the most prudent path.

Our quasi-privatization proposal replaces the pre-crisis moral hazard model with a durable, macroprudential, politically tenable framework that addresses the welfare and incentives of all involved stakeholders.

If you’re privvy to the details of the ongoing debate surrounding GSE reform and conservatorship exit, you may want to just skip to the meaty part, where the Boyd proposal is laid out in full. Otherwise, let’s start with the (very) storied history of the GSEs, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

Some background context

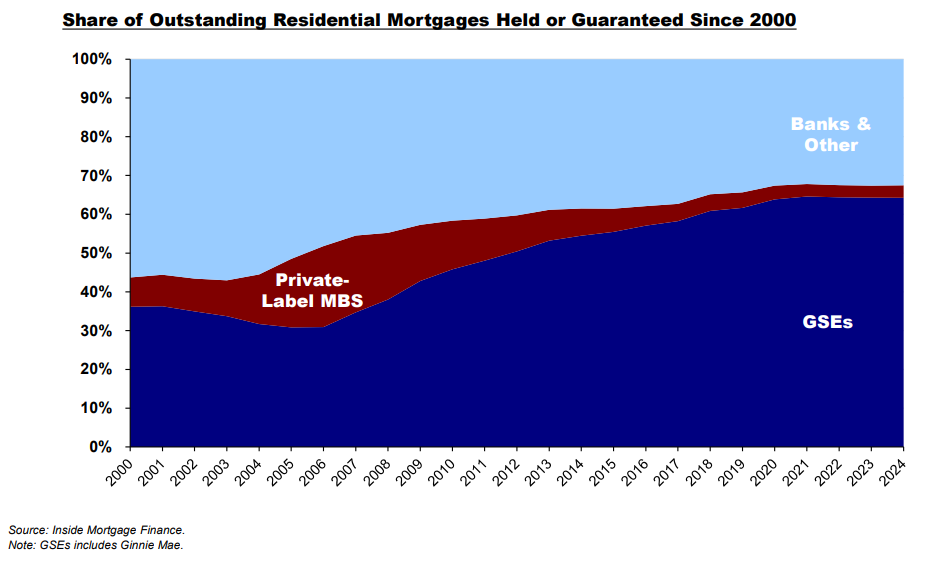

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (F&F), chartered in 1938 and 1970 respectively, remain the backbone of the US housing finance system, accounting for well over half of the nearly $15 trillion of residential mortgage debt across the nation.

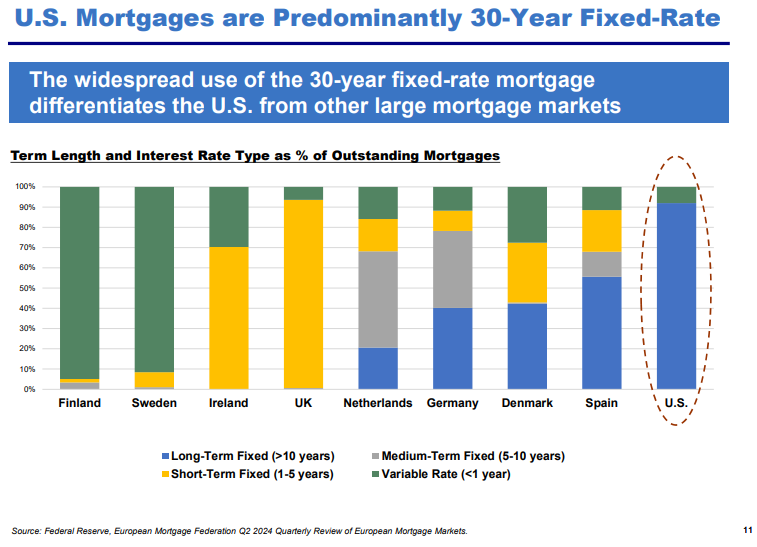

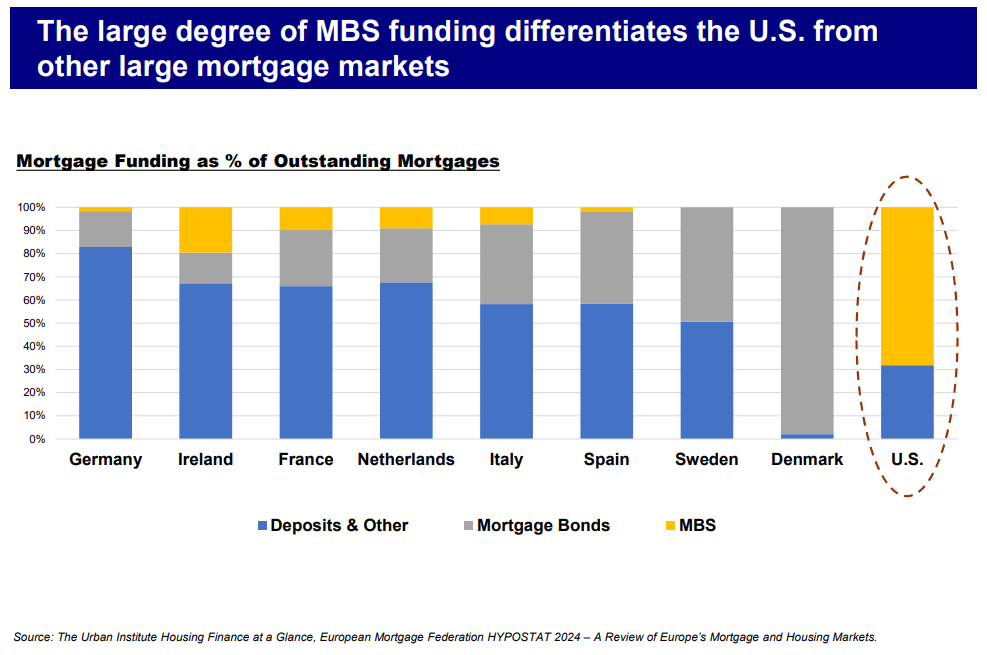

They play a central role in enabling widespread access to the 30-year, fixed-rate mortgage — a product that is rare outside the US — by enhancing affordability and liquidity.

In addition, the mortgage-backed securities (MBS) they guarantee comprise the vast majority of the “agency MBS” market, the second largest (most liquid) fixed-income market in the world after US Treasuries. This deep liquidity contributes to lower borrowing costs across the board.

Some clarification: F&F don’t make loans; they purchase loans from lenders, pool them into securities that are then sold to investors, and provide guarantees (for a fee) to make investors whole if the loans default. And they weren’t always under the operational control of the US government as they are now. For decades, they operated as publicly traded, shareholder-owned corporations with an implicit — though never explicit — government guarantee. Their success in fostering a national secondary mortgage market led to rapid expansion: at their pre-crisis peak, they supported roughly 73% of all newly originated mortgages. The scale and uniformity of this system helped reduce mortgage rates — by an estimated 20-60 basis points compared to a fully private market — and extended access even in less creditworthy or geographically remote markets.

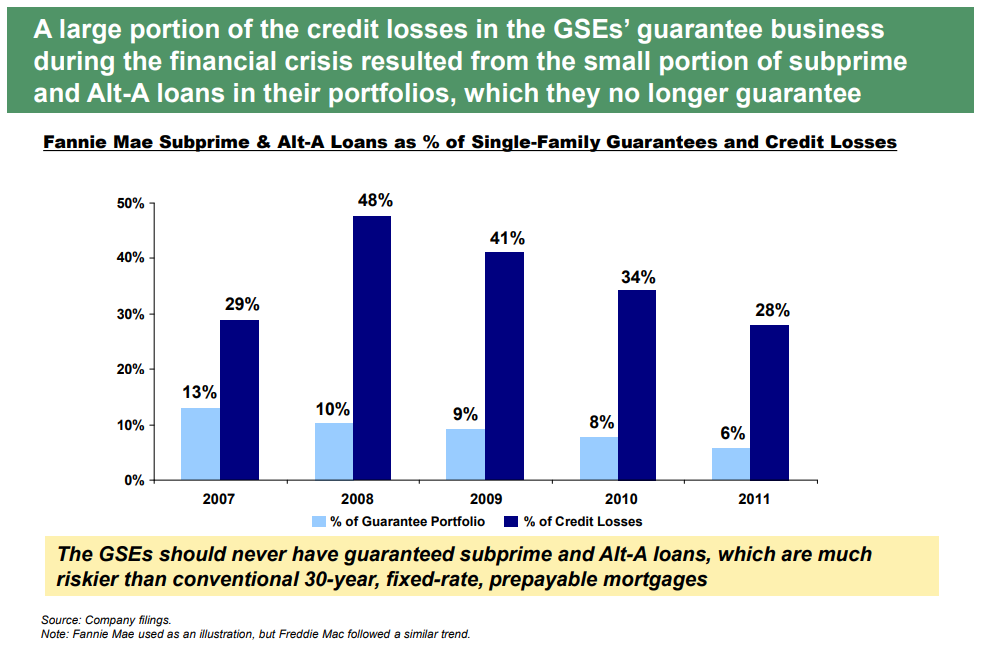

However, beginning in the 1990s and accelerating through the 2000s, both GSEs expanded into riskier Alt-A and subprime-adjacent markets, often under political pressure to promote homeownership and affordability.

They also deviated and diverged from their core function as a guarantor, becoming “akin to giant, highly-leveraged hedge funds that were able to fund themselves with debt just slightly more expensive than Treasury debt because of the ‘implicit’ guarantee of Uncle Sam. At their pre-crisis height, Freddie and Fannie managed a $1.6 trillion retained portfolio of MBS.”

Despite this increasing risk exposure, the GSEs operated with razor-thin capital buffers — typically under 0.5% — and charged guarantee fees (g-fees) far below levels consistent with actuarial soundness.1 Agency MBS nonetheless retained their AAA ratings not based on risk assessment or conservative underwriting, but because markets assumed the government would backstop losses. The resulting mispricing of risk eventually came to a head. When default rates rose and MBS values declines in 2007–2008, the already-thin capital buffers proved inadequate — and the enormous leverage layered atop what was considered a “safe and liquid” market suddenly became, to say the least, problematic.

Finally in September 2008, to prevent a complete collapse of the housing finance system, the government placed both firms into conservatorship, with Treasury eventually injecting a total of ~$191 billion in capital and taking warrants for 79.9% of the common stock. In doing so the previously implicit government guarantee was made explicit, and the US government formally assumed responsibility for supporting the mortgage market. Since then, the GSEs have remained under the control of the FHFA, acting as their conservator.

Now, if exercised, these warrants, would leave current common shareholders with only 20.1% ownership. More consequentially, the Preferred Stock Purchase Agreements (PSPAs) — the legal instruments by which Treasury provided capital support, explicitly intended to “prevent the GSEs from rebuilding capital” while policymakers decided on their future — included a “net worth sweep” clause requiring nearly all GSE profits to be remitted to Treasury as dividends rather than retained to the underlying firms themselves.2

The sweep was suspended in 2019 under Trump 1.0, allowing the GSEs to begin retaining earnings in rebuilding their capital base. However, in another unusual twist, instead of F&F paying a preferred shares dividend to Treasury, it was stipulated that the senior preferred stock value increases dollar-for-dollar by the amount of the earnings retained. This arrangement preserved the economic benefit for taxpayers while continuing to subordinate the rights of common shareholders.

Though F&F have now returned roughly 150-160% of the ~$191 billion in capital Treasury originally injected, the PSPA structure has caused the senior preferred claim to grow significantly. In total as of 2025, Treasury still holds the 79.9% warrants as well as senior preferred shares with a face value (“preference”) of approximately $341 billion. Thus, before a conservatorship exit could occur, this senior claim must be resolved — either through repayment, conversion, or cancellation — along with the governance implications of the warrant structure.3

Another key obstacle is capital adequacy. FHFA (strengthened as a regulator by the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008) has established stringent regulatory capital requirements via its Enterprise Regulatory Capital Framework (ERCF), finalized in 2020, which sets robust risk-based and leverage capital standards. As of Q3 2025, the combined ERCF requirement for F&F stands at approximately $252 billion — $140 billion for Fannie Mae and $112 billion for Freddie Mac.4

This capital requirement is central to the viability and timing of any exit from conservatorship. Meeting it solely through retained earnings — especially under the current arrangement where those earnings still grow the Treasury’s senior preferred stake — would likely take another decade or more.5

And even that isn’t sufficient. Once the PSPA and ERCF requirements are met, the GSEs must also resolve legal disputes stemming from the terms of conservatorship and the 2012 sweep amendment. This is critical as the range of legal disputes include litigation brought by legacy shareholders and other stakeholders challenging the validity of the government’s takeover.

Finally, an important change as of January 2025 stipulated that Treasury must provide written approval before conservatorship can end. Previously, FHFA could terminate conservatorship without Treasury approval if the capital and litigation conditions were met. But this restoration of Treasury consent means the executive branch now holds final decision-making power.

Why conservatorship can’t be permanent

So, if things are stable now then why can’t the status quo be permanent? The short answer is that there’s a lack of statutory basis — conservatorship was intended as a temporary emergency measure. Neither the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 nor subsequent legislation provides for perpetual government operation of a “nationalized-but-not-nationalized” entity. Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson, who led the 2008 rescue, was explicit that the bailout structure was chosen to avoid making the government the outright owner (>80% stake) of the GSEs — which would put their ~$7.6 trillion of obligations on the federal balance sheet — but equally explicit that taxpayer money should not support the old GSE model going forward.

And then there’s the fact that the Treasury’s stock warrants expire in 2028. As former Freddie Mac CEO Donald Layton noted, exiting conservatorship without reform would simply leave Treasury as the controlling shareholder, and unwinding that (through stock sales to the public) could take years. To avoid an interminable government ownership or a fire-sale of stock, something must be done — fairly soon — lest we prefer the GSEs being indefinitely owned and operated by Treasury. Granted, the status quo has stabilized the housing market in the short run, but it creates uncertainty and distortions in the long run. There are three key concerns on along these lines:

1) The current state of GSE conservatorship deters long-term planning and investment.

Private capital is reluctant to engage with or invest in the GSEs because their end-state is unknown. The common and junior preferred shareholders have been in litigation for years, and while most claims have been resolved in favor of the government’s actions, the uncertainty remains a distraction and overhang. More broadly, mortgage lenders and servicers operate under temporary guidelines and ever-evolving conservatorship mandates, which can change with each FHFA Director. For example, loan limits, program innovations, and credit policy shifts are harder to enact when the entities lack independent standing. This uncertainty ultimately can inhibit innovation in mortgage products or technology. A regulated, well-capitalized GSE outside of conservatorship would have more flexibility to invest in new systems (e.g., modernizing the loan origination or servicing infrastructure) or pilot new programs in a way that today might be viewed as beyond the narrow scope permitted in conservatorship.

2) Taxpayers are still explicitly on the hook for any losses via the PSPA funding commitment.

Currently, $252 billion of Treasury commitment remains available. While the GSEs have been profitable in recent years, in a severe stress (akin to 2008), they could again incur outsized losses that would drain their capital and require draws on Treasury. The longer we go without a resolution, the more the GSEs expand (they continue to guarantee trillions in new MBS each year), and the more taxpayers are exposed to tail risks. Moreover, because the GSEs cannot currently retain all earnings and cannot access equity markets, they rely on the PSPA as their only recourse in a crisis, which ultimately means reliance on the taxpayer.

3) The open‑ended status of conservatorship invites the politicization of housing finance.

Different administrations have different housing policy priorities. We have already seen swings: the prior administration moved to shrink the GSEs’ footprint and prepare for release, while the current administration has emphasized using them to expand equitable access. This seesawing political rhetoric injects uncertainty into the mortgage market and undermines investor confidence — analysts note that mere debates over ending conservatorship regularly widen agency MBS spreads. Effectively, this operates as a tax on mortgage holders.

In short, permanent conservatorship is not a sustainable solution. It lacks a firm legal foundation, creates uncertainty that stifles innovation and investment, leaves taxpayers indefinitely on the hook, and risks the GSEs being buffeted by shifting political winds or legal challenges. FHFA’s own strategic plan rightly seeks to end the limbo: it would ensure the GSEs can operate with a clear mandate, sufficient capital, and normal corporate governance under regulation, rather than as anomalies. The question is not whether to end conservatorship, but how.

Why a traditional IPO is suboptimal

Former FHFA Director Mark Calabria — a staunch advocate for shrinking the government’s footprint in housing finance — envisioned Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac as tightly regulated utilities post-conservatorship, not as free-market actors. The goal was to reintroduce private capital and accountability without discarding the structural benefits of standardization, liquidity, and countercyclical support that the GSEs provide through their government-adjacent status. That vision continues to guide the conversation.

Yet the pure-play privatization model — via traditional IPO, long-championed by Bill Ackman who is… wait for it… the owner of nearly $10 billion in Fannie Mae common stock — remains a weak and deeply flawed approach.6

IPOs depend on assumptions about market efficiency, rational pricing, and full alignment between shareholder incentives and systemic outcomes. These assumptions fall apart in the housing finance system, where political, credit, and liquidity risks interact in nonlinear ways. Thus, the traditional IPO route is unsound for (at least) three core reasons:

1) The guarantee can’t go away — markets know it, and the polls will show it.7

Pension funds, insurance companies, foreign central banks, and institutional portfolios hold trillions in agency MBS, using them as safe collateral in repurchase agreements, yield and duration supplements, and as cornerstones of liability-matching strategies — and they’re crucially, for better or for worse, an integral part of Fed monetary policy. If the government were to truly disclaim support for these instruments (implying that agency MBS holders would bear full credit risk) markets would fracture: spreads would widen, volatility would spike, and the cost of mortgage credit would surge by at least 25 but as much as 100 basis points, according to various estimates.

The political economy of this outcome is clear: these are undesirable outcomes for everyone involved — from the Fed to regional banks to homebuyers to investors — especially the US Treasury taxpayer (read: voter). No administration, regardless of partisan orientation, can afford the backlash from a sudden jump in mortgage rates.

2) The IPO path fragments the GSEs’ stabilizing role.

The GSEs’ countercyclical provision of liquidity — stepping in to purchase mortgages and MBS when private capital retreats, the GSEs’ most valuable function during periods of market stress — is not just a market outcome but a deliberate design feature enabled by their quasi-public status and implicit guarantee. In past crises, Fannie and Freddie served as market makers of last resort when private liquidity disappeared. Their ability to remain in the market has been essential to stabilizing credit markets and preserving access to housing finance.

This isn’t a fluke — and it can cut in the other (destabilizing) direction when the GSEs aren’t at least quasi-publicly governed. Fully privatized GSEs, governed solely by shareholder ROE expectations (as was the case in 2008), are unable step in during times of crisis; instead they’re forced to shrink their footprint just when they’re most needed, amplifying a credit crunch and exacerbating systemic risk.

3) An IPO of this size would impose untenable capital formation requirements.

Under the current ERCF, the combined capital target for F&F is roughly $252 billion. Achieving that through a traditional IPO would require an unprecedented equity raise — some estimates exceed $300 billion in funds raised for the government, given current market capitalizations. Worse, the IPO process would require Treasury to sell its 79.9% warrants — massively diluting legacy common shareholders — and leave the GSEs overleveraged relative to return expectations. The capital raise would also potentially happen at a steep discount (especially if rushed), causing a surge in the GSEs’ cost of capital which would further reduce confidence and compress investor appetite. Undersubscribed IPOs — nevermind this potentially being the largest share issuance of all time — are never not ugly.

None of this is to say that the current structure is acceptable. It isn’t. But it suggests that the alternative is neither a return to the pre-2008 hybrid model nor a leap toward pure privatization. Indeed, it suggests a third path: reform that preserves the stabilizing architecture of the system while introducing market discipline, capital strength, and regulatory oversight sufficient to prevent a recurrence of pre-crisis moral hazard.

The intellectual architecture for this third path emerged around 2016, during the Obama administration, when it became apparent that Congress would not pass comprehensive GSE reform. Regulatory and policy experts developed what is now commonly called the “reform-recap-release” approach — a framework for restructuring the GSEs’ charters and operational rules (reform), recapitalizing them to meet new, more robust standards (recap), and then releasing them from conservatorship under reformed governance (release).

Why a hybrid approach is prudent

We lend full credence to the political concerns that releasing the GSEs could lead to a return of the pre-2008 “heads we win, tails taxpayers lose” dynamic. In the pre‑crisis era, shareholders could (and did) push F&F to take on leverage and chase volume because the upside accrued to them while downside losses were implicitly backstopped.

Therein lies the massively consequential tradeoff. On the one hand, removing the government-guarantee status of agency MBS risks balooning MBS spreads thus diminished home affordability for milions of Americans (not to mention a ripple effect across financial markets — indeed there is still a lot of leverage in the system resting on the risk-free perception of agency MBS). On the other hand, maintaining an explicit guarantee, as is the case under conservatorship, makes mortgages cheaper and housing more broadly affordable — yet the taxpayer is on the hook for GSE liabilities in the event shit hits the fan.

In light of these challenges and numerous others, we propose a balanced, hybrid solution: a special government-held “golden share” to secure robust public control over mission-critical decisions. Unlike the historical ‘wink wink, nudge nudge’ reliance on an implicit guarantee, where the government was merely assumed to be a lender of last resort, a “golden share” held by Treasury establishes a concrete scaffolding around the entities’ long-term strategic governance. This share would confer no economic rights but significant voting rights, thereby preventing the GSEs from systematically engaging in excessively risky behavior driven purely by shareholder profit motives. Crucially, it provides investors with a clear, explicit assurance that the government has the authority to steer the long-term strategy in a macroprudential (even counter-cyclical) direction. Even more importantly, it takes the taxpayer off the hook.

In addition to the “golden share”, we propose that the GSEs be reconstituted as mutual entities, shifting ownership away from external public shareholders and toward the GSEs’ own lender partners.8 When GSE customers also collectively also have an economic ownership stake, this structure aligns incentives, providing adequate pressure for the GSEs to focus on leanness, efficiency, innovation, and, even more importantly, reasonable Return on Equity (ROE) expectations and actuarially fair g-fees. If the “golden share” provides the macroprudential guardrails, this mutualized ownership structure ensures sufficient micro-prudential accountability — from a day-to-day, operational standpoint.

The mutual + “golden share” structure also simplifies the capital raise problem. Rather than relying on speculative retail or institutional equity markets, the GSEs would recapitalize through retained earnings and member capital subscriptions. Over time, this mutual capital base — composed of redeemable stock tied to loan volume — could meet FHFA’s capital standards without overreaching. It is a patient, disciplined path to financial soundness.

The following outlines the high-level contours of our “reform-recap-release” proposal.

Reform: “Golden share” & governance charter fixes

Treasury holds a perpetual, non-economic “golden share” with voting rights over systemic risk (macroprudential) decisions, major capital actions, and charter-level changes.

This instrument replaces the PSPA while preserving some semblance of a backstop — a necessary condition for maintaining tight MBS spreads and systemic liquidity.

FHFA regulatory authority is reaffirmed; GSEs operate as regulated utilities with public mission lock-in.

The government guarantee transitions back from explicit to implicit — but this time rooted in a concrete, legal governance framework.

Recap: Capital formation via mutual ownership

Capital targets (~3% of assets / ~$250–300B) are met through a mix of:

Retained earnings (already accreted: ~$147B and growing); gap to FHFA requirement: ~$100B+

Filled through: organic earnings retention (~$75B by 2028) + FHLB member capital investments (~$10–15B annually)

New mutual capital subscriptions from eligible institutions — members purchase capital stock proportional to loan volume sold to the GSEs (modeled on the FHLB)

Treasury’s preferred shares are converted to non-economic golden equity, eliminating the need for a dilutive IPO or warrant exercise.

The GSEs remain in conservatorship until this mutual capital base is achieved, enabling exit without market disruption.

Common equity is cancelled9 (no residual claim once Treasury senior preferred and charter restructuring occur); junior preferred holders offered swap into new subordinated or mutual capital instrument (or negotiated recovery).

Release: Mutualized cooperative GSEs

Fannie and Freddie are rechartered as mutual entities, owned by a broad base of participating lenders.

These institutions hold membership stock that entitles them to capital distributions and voting rights, but also exposes them to economic risk — aligning incentives with prudence and sustainability.

Governance structures are modernized to reflect a utility model with public oversight, including FHFA supervision and Treasury’s golden share as a strategic failsafe.

Boyd Institute’s full 42-page proposal submitted to the FHFA:

This reform-recap-release framework is not a half-measure or technocratic workaround. It is a strategically comprehensive resolution to one of the longest-running and most consequential financial policy dilemmas in modern US governance. Indeed, the GSEs have been in “temporary” conservatorship for basically an entire generation; Fannie & Freddie represent the last remnants of the financial crisis of ‘08.

But we at Boyd believe that our proposal recognizes — and operationalizes — the reality that the GSEs are neither fully public utilities nor traditional private firms, and that any solution must respect the embedded systemic importance of the GSEs without simply entrenching the pre-crisis moral hazard regime. Importantly, this framework also avoids a binary political choice between “nationalization” and “Wall Street IPO.” It ends conservatorship not by selling the GSEs off to the highest bidder, but by recapitalizing them in a deliberate, scalable way that does not trigger massive dilution, volatility, or litigation. It lets retained earnings and member subscriptions — real, patient capital — do the heavy lifting. Crucially (for the current administration), the recap path is not just feasible by 2028, it is durable and politically sustainable.

To that end, we’d be remiss to not at least briefly outline…

How the mutual + “golden share” structure can be sold, politically

The most politically powerful feature of our proposed structure is also its most conceptually sound: it resolves the long-lingering GSE dilemma not by embracing Wall Street-style privatization, nor by entrenching federal control, but by building a system that directly aligns financial incentives with the GSEs’ public mission. That’s both good governance and a compelling message.

In our model, the GSEs are recapitalized as mutual utilities — owned by the same lenders who rely on them for market access and who will now have skin in the game. Instead of being driven by quarterly earnings and investor pressure, F&F would be governed by a membership base composed of community banks, credit unions, and other originators — institutions with a vested interest in long-term loan performance, not short-term volume. As one analysis puts it,

“The mutual ownership structure aligns incentives on credit risk, meaning that both the loan originators and the credit enhancers have direct exposure to credit risk and each will want to carefully monitor production.”

In other words, if a member bank knows it has capital at stake in the GSE system, it will originate loans with an eye toward long-term performance, not just selling volume. Moreover, the “golden share” provides what has always been missing from the GSE framework: an explicit public control mechanism. By giving the Treasury a non-economic class of governance rights — a “perpetual golden share” — we secure macroprudential safeguards, ensure that any major governance changes remain aligned with public interest, and and dispels the ambiguity that has historically fueled moral hazard and market distortion. It acts as a firewall between system stability and shareholder opportunism.

Politically and practically, we are concerned with the GSEs’ “duty to serve” the mortgage market. Downstream of this is the welfare of homebuyers, mortgage holders, and taxpayers — everyday Americans. In this sense, the structure sells itself if framed correctly. It’s a “utility, not a Wall Street windfall.” It honors taxpayer investment with a perpetual, priced federal backstop fee and monetizes Treasury’s senior claims transparently. It preserves affordability by reducing required returns on equity and minimizing g-fee pass-through. And it avoids the volatility, dilution, legal overhang, and MBS spread widening likely to accompany a speculative IPO.

Sequencing is also critical. Senior claims and retained earnings are addressed first through a negotiated path for resolving Treasury’s senior preferred and exercising (or monetizing) the warrants. Only then is capital raised from member institutions — ideally through expanded charters that welcome smaller lenders — allowing mutualization to proceed without junior-ahead-of-senior conflicts. Exit is tied to clearly published ERCF capital thresholds and litigation resolution, giving credit markets and CBO scorekeepers confidence and predictability.

Finally, this conservatorship off-ramp approach builds a winning political coalition. Small lenders — the community banks and credit unions often left behind by megabanks — gain access, voice, and ownership. Housing advocates can back a mutual charter that includes enforceable duty-to-serve and affordable housing goals, protected by golden-share veto rights. Budget hawks see real receipts via the commitment fee, and progressives can point to systemic reform that doesn’t enrich hedge funds.

Ultimately, this is a structure designed to endure. It replaces ambiguity with clarity, speculative equity with patient capital, and regulatory capture with a stable, bipartisan governance framework. As housing challenges evolve — through technological change, demographic shifts, or climate risk — a mutual + “golden share” ownership structure is adaptable, with input from its diverse members and guidance from its public overseers.

It’s more nimble than a government bureaucracy and more publicly-minded than a private utility. If done right, this isn’t just the optimal GSE conservatorship exit plan — it’s the last one we’ll need.

That is, 0.45% equity against the outstanding value of their mortgage guarantees. This may have actually been a sufficient level of capitalization had the GSEs not veered into guaranteeing subprime mortgages.

Starting in 2012, the original 10 percent dividend on the senior preferred stock was replaced by a “sweep” dividend of almost all F&F’s earnings — a highly unusual move that not only prevented the GSEs from recapitalizing but actually forced their decapitalization. This unsurprisingly led to various lawsuits alleging that this constituted an unfair seizure of value from the public shareholders who had already been disenfranchised during conservatorship. While the government won almost all the lawsuits, the bad feelings on the part of those shareholders – by that time, mostly professional investors making a highly speculative investment – did not go away.

The current regulatory minimum, based upon formulae referred to as the Enterprise Risk Capital Framework (ERCF), generates a requirement of about $350 billion, inclusive of the five percent cushion, and acts as a “high” estimate. The “middle” estimate, which builds on the previous Conservatorship Capital Framework while also incorporating a countercyclical buffer (the enhanced CCF), generates a requirement of about $230 billion, also inclusive of the buffer.

In the last three years, the average net income for F&F was $26.3 billion. However, GSE earnings are sensitive to economic conditions, in particular changes in home prices, all of which have been very favorable in recent years. Thus, for planning purposes, a slightly more conservative estimate of net earnings of $20 billion per year seems reasonable going forward. As of the end of 2024, the combined net worth of F&F was $154 billion. That means it will take roughly another 10 years to reach the high estimated capital requirement of $350 billion, but only about four years to reach the middle estimate of $230 billion.

This represents a decline from earlier 2024 estimates due to improved credit conditions and adjustments in the countercyclical buffer. The ERCF includes several components: a minimum CET1 requirement of 4.5%, plus multiple buffers — a stress capital buffer (currently 0.75% of adjusted total assets), a stability capital buffer (determined by market share calculations), and a countercyclical capital buffer (currently 0.0%). These buffers are designed to maintain safety and soundness similar to requirements for US globally systemically important banks (G-SIBs). (Source)

What could be a reasonable plan to dispose of the common shares obtained through exercising the 79.9 percent warrants and any shares from a conversion of the senior preferred stock? The decision to sell such a large number of shares – a very significant amount both in terms of dollar value (likely multiples of the largest common stock sale ever) and ownership stakes in each of F&F – should be made by Treasury based on technical market considerations after presumably being advised by equity market experts. It could perhaps take the form of a series of large, underwritten “secondary” sales from time to time, or perhaps selling modest amounts every day, or anything in between. Regardless, to avoid pushing strongly down on the price of the common shares, sales will need to be spread out over a large number of years.

However, before undertaking any such sales, a major policy decision is required. The very definition of conservatorship is that the government, currently through the FHFA, is in operational control of F&F, rather than their shareholders. While this will end when the GSEs exit conservatorship, the reality is that the government will still be in operational control of F&F, but instead through Treasury as the controlling majority owner of the companies’ shares. Some dub this a form of “conservatorship by other means.” The publicly owned common shareholders will thus still be significantly disenfranchised, and the shares will undoubtedly trade at a lower price to reflect this. This means the share sales by Treasury will produce far less revenue than might be expected.

One thing Ackman does get right, in our view, is that GSE capital ratios need not be so stringent — but, that is, only if a pure-play IPO is avoided.

Ackman says that this implicit guarantee would persist even in the event of a pure-play IPO — similar to how it is implied that a systemically important bank like JP Morgan, if it failed, would garner a government bailout. This is perverse, and precisely the line of thinking that enabled rampant morally hazardous behavior in the run up to the Great Financial Crisis.

This structure has isn’t without precedent. In fact, “Fannie Mae used to require its seller-servicers to invest in Fannie Mae shares” as a condition of selling loans. And Freddie Mac, before its public share offering in 1989, was owned by the FHLBs (which in turn are owned by member institutions) — essentially a form of mutual ownership that was later unwound during privatization. We are, in a sense, returning to the roots of the GSE concept by re-aligning them with the banking system and mortgage lenders, rather than with Wall Street equity investors.

There is wiggle room for a negotiated, discounted redemption of common shares. But the common stock, since the GFC, has traded solely on the basis of its value as a call option (of sorts) on privatization — its value is purely speculative, not tied to underlying earnings or cash flows (per the PSPA). Because of this, Ackman and other common shareholders should not necessarily be made whole, as common shareholders are always the lowest on the totem pole.

Well done. As a former GSE employee (20 years) who survived the GFC - this is a thoughtful and well-reasoned approach. Though I think you understated the risk of the pure IPO play.

There are so many things that can go wrong with a pure IPO strategy and the execution risk is extremely high. There are (quite literally) a trillion reasons why that risk makes no sense to take - especially when the best case scenario is a post-conservatorship environment that stabilizes the long term governance and financial foundation of the housing finance system AND where consumers get the same 30 yr FRM they get today and the MBS market works the same as it did yesterday.

The only reason why the current common stock exists is because the government didn't want to be forced to consolidate the GSE MBS as US sovereign debt. Forcing the companies to go through a real bankruptcy, with a suspension of P&I payments on the MBS would have crashed the banking system.

If F&F were "normal" companies, the current common stock would have been wiped out. The existing shareholders should get nothing (or maybe discounted warrants) to buy the IPO'd stock.