Contact Tracing for Crime — Unlocking the Frozen City

The second-place essay in our contest, authored by The Calipers

The Calipers is the pseudonymous author of a blog about information that wants to be free. First, the idea is to develop useful theories that have predictive power. The author’s biases are chiefly related to free speech maximalism, fewer regulations on markets, and bioliberalism.

In this essay, which placed second in our Essay Contest, The Calipers posits that urban gun violence operates like a contagious disease spreading through dense social netowks — and that mapping the “superspreader” people and places that concentrate violence could sharply reduce crime and, in turn, unlock frozen neighborhoods for new housing and investment.

Chicago’s South Shore offers lakefront views beside a world-class university. Boston’s Roxbury and Philadelphia’s Strawberry Mansion look just as promising on paper. But developers refuse to put up cranes, and young professionals refuse to nest. Crime accomplishes what NIMBYs dream about: keeping neighborhoods effortlessly frozen. Rational actors, however open-minded, must still manage risks to life and property.

Cities historically competed as production centers, offering wage premiums that justified higher rents and offset day-to-day inconveniences. But by 2000, urban rents began rising faster than wages, revealing demand driven by consumption amenities like access to desirable social networks.1 Sidewalk cafes, theaters, and nightlife attract desirable, productive residents only when they can be enjoyed without fear of assault.

Education level and family structure predict who flees dangerous cities. Cullen and Levitt tracked 127 major U.S. cities from 1970 to 1993, finding each additional reported crime associated with one fewer resident. College-educated households proved 50% more responsive than high school dropouts, with families with children fleeing at twice the rate of childless households.2 Most relocate to the suburbs.

The damage from educated workers fleeing crime is multiplicative. Each percentage point increase in college graduates raises wages for all workers by roughly one percent.3 Proximity enables skill absorption: the electrician learns project management from the accountant, picks up contract negotiation from the lawyer, and adopts digital scheduling from the designer. Good or bad, we learn from neighbors.

Boys copy boys, crews copy crews

Between 1986 and 1998, Denmark settled refugees into various towns quasi-randomly, creating a natural experiment on peer effects. Each standard deviation increase in the share of young convicted criminals living in a neighborhood raised male youth conviction rates by 5-9%, with effects concentrated among boys ages 10-14.4 Social networks choose which skills diffuse, creating young male predators or protectors.

Around half of arrests for carjacking, robbery, or burglary capture two or more people. Committing these requires partnerships with getaway drivers, lookouts, and resellers. These criminal partnerships aggregate into citywide networks, as Papachristos and Bastomski found in Chicago. Any two neighborhoods in that city connect through fewer than two criminal partnerships, regardless of physical distance.5

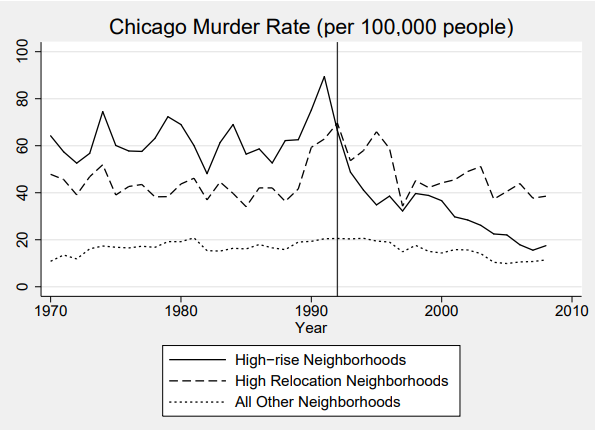

Public housing demolitions provide a natural experiment in disrupting these networks. Chicago’s demolitions in the 1990s forced entire buildings to relocate simultaneously, providing more effective results than voluntary relocation programs where 57% of youth continued visiting friends in their old neighborhoods. By contrast, the fully displaced children experienced 14% fewer violent crime arrests.6

Most released prisoners return to the same few communities from which they came. Their homecoming regenerates these partner-in-crime networks and keeps those blocks perpetually uninvestable. Chamberlain and Wallace (2016) found recidivism 67% higher where ex-offenders cluster, even after adjusting for poverty and family structure.7 The same human density that builds cities also rebuilds crime.

Unlocking frozen neighborhoods removes barriers to housing supply. This differs from demand-driven “gentrification,” or coerced flight of poor residents. Pennington (2021) showed the difference using San Francisco building fires as a natural experiment. Rents actually fell 2% within 100 meters of new construction, while displacement risk dropped 17%.8 Locally, supply effects dominate demand effects.

Graphing the superspreaders of violence

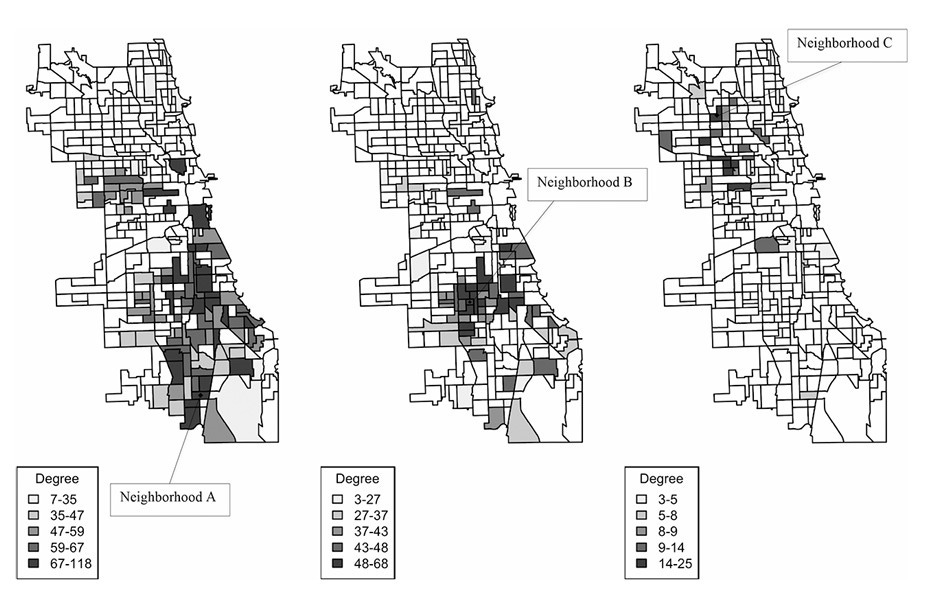

In the 1990s, policing began to absorb the logic of asymmetry. Systems like CompStat used statistical mapping to shift officers toward the five percent of blocks producing half the crime, effectively putting the “law of crime concentration” into practice.9 The next leap came from modeling which people exert outsize influence, as in Stockholm, where the most connected 5% of offenders drive 22% of all crime.10

Targeting the small number of repeat, network-central offenders consistently works. Between 2001 and 2015, 24 quasi-experimental programs—almost all in the United States—cut shootings and homicides in statistically significant ways. The gains spread outward instead of shifting crime elsewhere. This effect disappeared only when cities’ leadership turnover dissolved their focus on the highest-risk offenders.11

Conversely, a handful of visible guardians can stop the spread of antisocial behavior. In randomized field trials, unarmed security guards cut total crime by 16%.12 Business Improvement Districts scale the same logic by pooling merchants’ resources for private security. In Los Angeles, each $10,000 spent on BIDs prevented over three crimes, saving roughly $200,000 in avoided harm, from victim losses to court costs.13

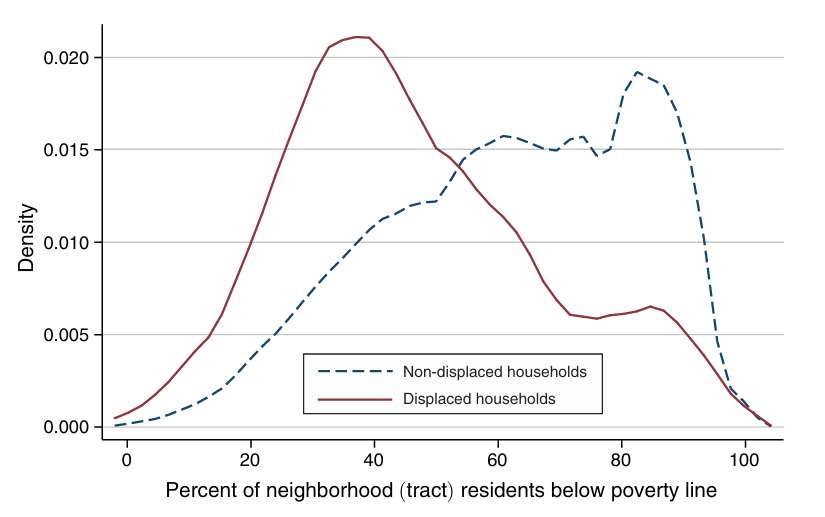

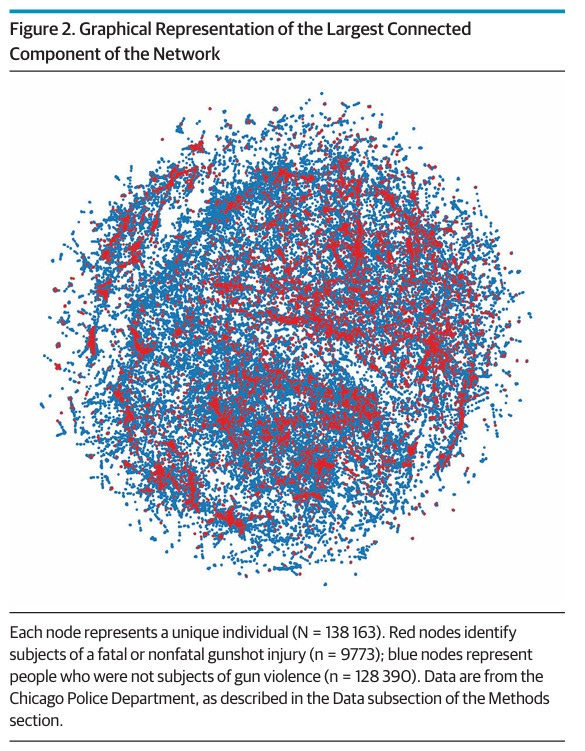

But gun violence follows social rather than spatial boundaries. Victims and offenders occupy the same networks, not necessarily the same blocks. In Chicago from 2006-2014, 63% of shootings followed social contagion: victims were shot an average of 125 days after someone they’d been arrested with.14 Gang Twitter captures the grief-to-retaliation cycle, with aggressive posts spiking within 48 hours of mourning a death.15

Mandate a new notifiable disease

Network analysis of gang associates faces Fourth Amendment barriers requiring warrants and probable cause. Yet states already mandate reporting of communicable diseases (like measles) with contact tracing under public health authority. The “Cardiff Model” from the UK, where hospitals shared data with police, produced a 42% reduction in hospital admissions for violence and $32 saved per $1 spent.16

The READI trial in Chicago reveals the cost of legally constrained algorithms. Its machine-learning model, despite constraints on using juvenile and race-related data as predictors, identified men at higher predicted risk than outreach workers did (14% vs. 9% predicted future gun violence involvement). Yet only 37% of algorithm referrals enrolled. Many couldn’t be located; those found often distrusted staff they’d never met.

Outreach workers achieved 78% enrollment among their own referrals, meaning men they already knew and had screened for “readiness.” Among those participants, shooting and homicide arrests fell 79%. The authors attributed the effectiveness gap to information the algorithm couldn’t access: street names, home addresses, network relationships, and risk signals from men without public arrest histories.17

The 20-month program spent $52,000 per participant because finding the hubs in Chicago’s victim-offender network demanded human judgment. But what if hospitals could map those networks automatically, using their own security data? By 2018, 42 percent of hospitals already tracked visitors systematically. Analyzing these logs could reveal the connectors—the ones who show up for more than one gunshot patient.

Forty-eight states already require hospitals to report gunshot wounds to police as crimes, but not to health departments as contagious conditions. Classifying gun violence as a contagious condition could unlock Cardiff’s 42% violence reduction in U.S. cities. Public health workers could trace contacts for prevention using existing data, following the 125-day transmission window from victimization to revenge.

Audit the girlfriend supply chain

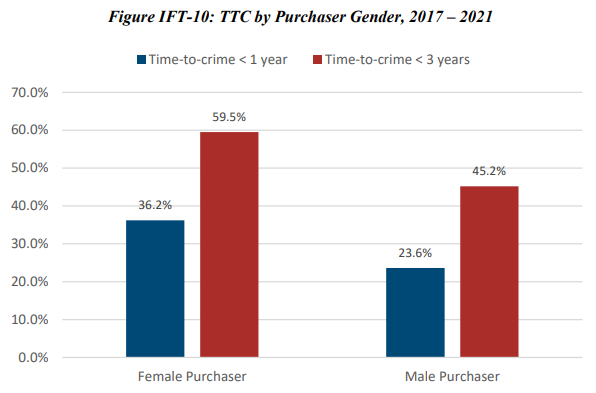

Guns purchased by women reach criminals faster,18 making them a strategic chokepoint. Philadelphia provides scale: women commit fewer than 10% of shootings but account for 24% of straw-purchase arrests since 2018.19 Case studies reveal hub outliers: one Minneapolis woman moved 62 guns in a single month.20 Yet prosecutors charged 12 buyers among 12,700 denied sales ATF investigated in 2017—just 0.09%.21

GAO officials explain that denial cases are high-volume, expensive to investigate, and so get triaged below cases against direct offenders.22 But civil courts can provide an alternative when prosecutors won’t act. In 2015, a Milwaukee gun store was held liable for nearly $6 million after assisting in a straw purchase of a gun later used against two police officers.23 Civil liability, though, depends on individual victims filing suit.

Mandate screening at the point of sale. When risk flags arise, such as a buyer taking phone instructions, flag it like pseudoephedrine.24 The goal is to add friction that spares unwitting accomplices. Operation LIPSTICK did this socially, educating women about buying guns for partners or felons who couldn’t legally own them. It cut gun crimes by women 33% in Boston and inspired a women’s group in Philadelphia.25

Connecticut’s permit-to-purchase law correlates with 40% fewer gun homicides;26 Missouri’s repeal increased murders 14%.27 The causal evidence for upstream administrative regulation is strong. But ATF’s own metrics reward seizures and arrests, not disrupted supply chains. The result is structural underweighting of the retail link, the last point within agency reach and where prevention is cheapest.28

Fortify or flatten the sanctuaries

High-rises serve as bases of operations for criminal gangs. Chicago’s HOPE VI demolitions from 1992 to 2007 destroyed that ecology. In affected neighborhoods, murders fell 11%, assaults 14%, and robberies 21%. Destroying the buildings, not citywide trends, caused these drops. Across 121 cities receiving the HOPE VI grants from HUD, murders dropped 3% citywide, meaning crime did not just relocate.29

Benefits show up long before the wrecking ball. A timing analysis of Chicago’s public-housing demolitions found crime falling as soon as residents received eviction notices, months before demolition began, and staying low for at least five years.30 Once shootings stopped spreading through social contact, the city crossed back into the realm of credit. Banks could underwrite, builders could plan, permits could move.

The nationwide data confirms it: crime reduction raises property values. Pope and Pope analyzed 3,000 urban zip codes from 1990-2000, matching similar neighborhoods across different cities to isolate the causal impact of crime. Where crime fell by half, values rose 7-19 percent.31 Housing authorities can systematically identify which buildings house the densest criminal networks for demolition and fortification.

In New York’s public housing data, crime rose with taller buildings and more households sharing an entrance. Newman’s 1996 analysis found 44% of felonies occurred in elevators, hallways, and lobbies. When Clason Point, a Bronx rowhouse project, redesigned those spaces into lockable yards owned by small, identifiable resident groups, serious crimes fell by 61%.32 Flatten the high-rises. Fortify the rest.

Clear, hold, build

Crime reduction removes the primary barrier to construction: NIMBYism. In Scally and Tighe’s survey of New York developers, safety and crime dominated (64%) other reasons for community opposition to subsidized low-income housing. This resistance causes construction delays, permit denials, and reduced unit counts, such that subsidized developments show a -.43 correlation with zip code white population.33

Overcoming that political veto permits construction. Profitability determines whether it happens. After crime began falling in the late 1990s, Philadelphia still faced an appraisal gap: market prices remained below construction costs. The city’s 2000 property tax abatement on new construction closed that gap, adding over 60,000 units across the next two decades and reversing half a century of population decline.34

But construction gains are at risk when a criminal diaspora reconcentrates in the old haunt. Hurricane Katrina scattered Louisiana’s ex-prisoners when Orleans Parish lost half its housing. Kirk found each additional homecoming parolee per 1,000 residents raised one-year reincarceration 11%.35 When the network reconstitutes, the chill returns: and so does the pressure on every safe neighborhood absorbing the overflow.

Break the fever, thaw the freeze

The fear of catching strays locks some neighborhoods in place and overheats others. In neighborhoods with strong locational fundamentals, violence overwhelms geographic value. Projected rents can’t cover construction costs, so nothing gets built. Meanwhile, educated families are displaced into adjacent neighborhoods, creating a scarcity premium driven by an artificially constrained supply of safer housing.

The interventions catalogued above—hospital-based network mapping, straw purchaser interdiction, strategic demolition—work because violence spreads through people, not places. No offender is an island; each is a node in a web of co-offenders, girlfriends, and grieving friends whose connections predict the next shooting. Targeting these nodes severs transmission, so rents can rise to match the location.

Construction is finally profitable. New supply relieves pressure on adjacent safe neighborhoods; prices fall as the scarcity breaks. Families with children stop fleeing for the suburbs. College graduates stay, and the electrician learns how to bid contracts in the lobby of his new high-rise. Bubba’s wages rise a percentage point as the reclaimed neighborhood fills with graduates. Proximity pays anew in the unfrozen city.

Glaeser, Edward L., Jed Kolko, and Albert Saiz. “Consumer City.” Journal of Economic Geography, vol. 1, no. 1, 2001, pp. 27-50.

Cullen, Julie Berry, and Steven D. Levitt. “Crime, Urban Flight, and the Consequences for Cities.” The Review of Economics and Statistics, vol. 81, no. 2, 1999, pp. 159-69. The authors use instrumental variables (state prison policies) to establish that crime causally drives depopulation.

Moretti, Enrico. “Human Capital Externalities in Cities.” Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics, edited by J.V. Henderson and J.F. Thisse, vol. 4, Elsevier, 2004, pp. 2243-91

Damm, Anna Piil, and Christian Dustmann. “Does Growing Up in a High Crime Neighborhood Affect Youth Criminal Behavior?” American Economic Review, vol. 104, no. 6, 2014, pp. 1806-32.

Papachristos, Andrew V., and Sara Bastomski. “Connected in Crime: The Enduring Effect of Neighborhood Networks on the Spatial Patterning of Violence.” American Journal of Sociology, vol. 124, no. 2, 2018, pp. 517-68.

Analyzing 172,714 individuals arrested together in Chicago (1999-2004), finds that crime spreads primarily through social networks rather than just geographic proximity. A 1% increase in crime among network-connected neighborhoods raises local crime by 0.67%, versus only 0.41% for merely adjacent neighborhoods.

Chyn, Eric. “Moved to Opportunity: The Long-Run Effects of Public Housing Demolition on Children.” American Economic Review, vol. 108, no. 10, 2018, pp. 3028-56.

Using Chicago demolitions from 1995-1998 as a natural experiment, finds displaced children are 9% more likely to be employed and earn 16% more as young adults, with 14% fewer violent crime arrests.

Chamberlain, Alyssa W., and Danielle Wallace. “Mass Reentry, Neighborhood Context and Recidivism: Examining How the Distribution of Parolees Within and Across Neighborhoods Impacts Recidivism.” Justice Quarterly, vol. 33, no. 5, 2016, pp. 912-41.

Pennington, Kate. “Does Building New Housing Cause Displacement?: The Supply and Demand Effects of Construction in San Francisco” (Working Paper, UC Berkeley, June 2021), https://ssrn.com/abstract=3867764.

Weisburd, David, Taryn Zastrow, Kiseong Kuen, and Martin A. Andresen. “Crime Concentrations at Micro Places: A Review of the Evidence.” Aggression and Violent Behavior, vol. 78, 2024, Article 101979.

Lindquist, Matthew J., and Yves Zenou. “Key Players in Co-Offending Networks.” CEPR Discussion Paper no. DP9889, Centre for Economic Policy Research, June 2014. SSRN,

Braga, Anthony A., David L. Weisburd, and Brandon Turchan. “Focused Deterrence Strategies and Crime Control: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Empirical Evidence.” Criminology & Public Policy, vol. 17, no. 1, 2018, pp. 205-250.

Ariel, Barak, et al. “’Lowering the Threshold of Effective Deterrence’—Testing the Effect of Private Security Agents in Public Spaces on Crime: A Randomized Controlled Trial in a Mass Transit System.” PLOS One, vol. 12, no. 12, 2017, e0187392.

Cook, Philip J., and John MacDonald. “Public Safety Through Private Action: An Economic Assessment of Business Improvement Districts.” Economic Journal, vol. 121, no. 552, 2011, pp. 445–462.

Green, Harel Shapira, Ben Horel, and Andrew V. Papachristos. “Modeling Contagion Through Social Networks to Explain and Predict Gunshot Violence Among Young Men in Chicago.” JAMA Internal Medicine, vol. 177, no. 3, 2017, pp. 326-33.

Using 2006–2014 Chicago police data on 138,000 individuals, the authors model gun violence as a social contagion process. They find that 63 percent of shootings propagate through co-offending networks, with an average 125-day lag between victim and “infector,” and that a small, densely connected subset of people accounts for most transmission.

Patton, Desmond U., et al. “Expressions of Loss Predict Aggressive Communications on Twitter Among Gang-Involved Youth in Chicago.” npj Digital Medicine, vol. 1, 2018, Article 57. Analyzing 8,500 tweets from gang-involved youth, the study finds that posts expressing grief increase aggressive tweets by 13% the next day and 21% within two days, mapping a 48-hour escalation window between mourning and retaliation.

Florence, Curtis, et al. “Effectiveness of anonymised information sharing and use in health service, police, and local government partnership for preventing violence related injury: experimental study and time series analysis.” BMJ, vol. 342, 2011, d3313.

Bhatt, Monica P., Sara B. Heller, Max Kapustin, Marianne Bertrand, and Christopher Blattman. “Predicting and Preventing Gun Violence: An Experimental Evaluation of READI Chicago.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 139, no. 1, 2024, pp. 1-56.

Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. “National Firearms Commerce and Trafficking Assessment (NFCTA): Crime Guns Recovered and Traced in the United States and Territories, Volume II.” 2024.

36% of female-purchased crime guns recovered within one year versus 24% for male-purchased guns (36 ÷ 24 = 1.5, or 50% faster diversion)

Siegel, Rachel. “Women Are Buying Guns for Men Who Can’t. In Philly, Prosecutors Are Cracking Down.” The Trace, 7 July 2025, https://www.thetrace.org/2025/07/straw-purchasing-guns-women-philadelphia/.

“Minnesota couple pleads guilty to straw purchasing 97 guns.” KSTP, https://kstp.com/kstp-news/top-news/minnesota-couple-pleads-guilty-to-straw-purchasing-97-guns/.

United States Government Accountability Office. Law Enforcement: Few Individuals Denied Firearms Purchases Are Prosecuted and ATF Should Assess Use of Warning Notices in Lieu of Prosecutions. GAO-18-440, Sept. 2018, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-18-440.

The report documents that of approximately 112,000 federal firearm denials in 2017, “ATF referred about 12,700... U.S. Attorneys had prosecuted 12” (12 ÷ 12,700 ≈ 0.09%).

GAO, Law Enforcement, GAO-18-440. Officials described denial investigations and prosecutions as “high volume” requiring “use of their limited resources.”

“Milwaukee gun shop found liable: Outlier or new normal?” The Christian Science Monitor, 14 Oct. 2015, https://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Justice/2015/1014/Milwaukee-gun-shop-found-liable-Outlier-or-new-normal.

“Stores are required to keep personal information about purchasers for at least two years after the purchase of these medicines.” — Legal Requirements for the Sale and Purchase of Drug Products Containing Pseudoephedrine, Ephedrine, and Phenylpropanolamine, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 9 Mar. 2006, www.fda.gov/drugs/information-drug-class/legal-requirements-sale-and-purchase-drug-products-containing-pseudoephedrine-ephedrine-and.

Shaw, Julie. “Attorney General Josh Shapiro Announces New Partnership to Combat Gun Violence in Philadelphia.” The Philadelphia Inquirer, 18 July 2019, 12:08 p.m., https://www.inquirer.com/news/pennsylvania-attorney-general-josh-shapiro-gun-violence-philadelphia-straw-purchasers-new-partnership-20190718.html.

Rudolph, Kara E., et al. “Association Between Connecticut’s Permit-to-Purchase Handgun Law and Homicides.” American Journal of Public Health, vol. 105, no. 8, 2015, pp. e49-e54, https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/full/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302703.

Webster, Daniel W., et al. “Effects of the Repeal of Missouri’s Handgun Purchaser Licensing Law on Homicides.” Journal of Urban Health, vol. 91, no. 2, 2014, pp. 293-302, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3978146/.

GAO, Law Enforcement, GAO-18-440. “ATF policy provides that field divisions may send ‘warning notices’ to denied persons in lieu of prosecution, but ATF has not assessed field divisions’ use of these notices, which could provide greater awareness of their deterrence value and inform whether any policy changes are needed.”

Hartley, Daniel A. “Blowing it Up and Knocking it Down: The Effect of Demolishing High-Concentration Public Housing on Crime.” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Working Paper 10-22, June 2013.

Sandler, Danielle H. 2017. “Externalities of Public Housing: The Effect of Public Housing Demolitions on Local Crime.” U.S. Census Bureau CES 16-16.

Pope, Devin G., and Jaren C. Pope. “Crime and Property Values: Evidence from the 1990s Crime Drop.” Regional Science and Urban Economics 42, nos. 1–2 (2012): 177–188. doi:10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2011.08.003.

The top decile saw violent crime fall by approximately 209 per 10,000 residents (a 62% reduction from the sample’s average 1990 baseline of 336), generating property value increases of 7.5-9.5% for violent crime and 14.5-19.5% for property crime.

Griffiths, Elizabeth, and George E. Tita. “Homicide In and Around Public Housing: Is Public Housing a Hotbed, a Magnet, or a Generator of Violence for the Surrounding Community?” Social Problems, vol. 56, no. 3, 2009, pp. 474-493.

Scally, Corianne Payton, and J. Rosie Tighe. “Democracy in Action?: NIMBY as Impediment to Equitable Affordable Housing Siting.” Housing Studies, 2015

Peter, Tobias. “Philadelphia’s Revival Is Now at Risk.” City Journal, 2025, https://www.city-journal.org/article/philadelphia-revival-property-tax-abatement.

Kirk, David S. “A Natural Experiment of the Consequences of Concentrating Former Prisoners in the Same Neighborhoods.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 112, no. 22, 2015, pp. 6943-48.

Incredible as always Calipers

This is great. I don't understand something, though: if the resulting disbursement through strategic demolition works to break these nodes, why doesn't the same effect occur when Katrina prisoners were disbursed?

Anyway, fascinating piece.