Housing as a Capital Markets Problem

The third-place essay in our contest, authored by Mike Fellman

Mike Fellman is the author of the Substack publication Housing Hell. He is an economist, chess olympian, and real estate finance expert who formerly worked at Freddie Mac and the International Monetary Fund. In this essay, which placed third in our Essay Contest, Mike proposes shifting focus from pure zoning debates to the cost and structure of capital.

Introduction:

High rents have been a very salient issue in most of the developed world since 2021. In the United States, since 2019, average rents have gone up about 21 percent. The rent surge is even more extreme in some so-called superstar cities, which offer excellent employment opportunities and many cultural amenities. Rents in New York City, arguably the most iconic American metropolis, have increased 34 percent since 2018. Many explanations have been put forward as to why rents are so high. The YIMBY movement tells a “quantity” or “zoning” story, which treats land use rules as a semi-binding cap on housing production. This creates a classic economic shortage and raises prices. Some assert that continued concentration in the rental housing sector raises rents because bigger landlords are more aggressive in demanding rent increases or may engage in price fixing. Virtually nobody talks about what is the biggest factor both constraining development and which explains high housing costs, namely, very high required rates of return to either construct or operate rental housing. Housing is a capital markets problem.

Real estate is one of the most capital-intensive industries in the world. Since buildings are some of the longest-lived assets in the economy, banks and other lenders usually, though not always, willingly lend against them at reasonable rates. However, equity capital to finance real estate deals is very expensive. For a ground-up construction project, investors usually demand a baseline minimum of a 20 percent internal rate of return or IRR.1 For the acquisition of an existing structure, investors usually demand a minimum IRR in the high teens. These high rates of return are the result of the illiquidity of real estate, the substantial risk of operating rental housing, and the high level of risk associated with construction projects.

High hurdle rates have profound implications for the real estate sector. Since capital is expensive because required returns are high, the main bottleneck holding back more housing production is low returns. Unfortunately, low returns can even be a bottleneck in high-demand cities frequently vilified as NIMBY.2 Any housing policy which seeks to address affordability must confront the reality that high costs of capital frequently necessitate that only projects with high and rising rents can move forward. This presents a paradox for advocates of land use reform as a panacea to high housing costs. If capital costs are high, project returns must be high, and that is fundamentally incompatible with falling rents.

This paper is divided into three sections. First, I lay out the basic economics of multifamily development and operation. I then explain why traditional solutions like upzoning or relaxing land use policies may do little to address affordability. Lastly, I provide solutions to address high housing costs.

The Economics of Multifamily Housing

Multifamily housing is IRR driven. Investors will not fund deals, be they ground-up projects or acquisitions, unless they clear IRR hurdle rates. These rates can depend on the regional market, but are usually 20 percent for ground-up development and the high teens for acquisitions. These numbers however are minimum baselines. Investors often demand more. In this section, we will explain the basic economics of acquisitions and ground-up deals.

The Economics of a Multifamily Acquisition

Any multifamily property is valued by its capitalization rate or cap rate. Cap rates are defined as the yearly rental income divided by the property value. Importantly, when determining net rental income, debt service costs are excluded. Cap rates can also be used to value buildings. Say a building generates $500,000 in yearly net rental income. If cap rates in the area for comparable buildings are 5 per cent, we can infer a building value of 10 million dollars.3

Surprisingly, cap rates tend to stay within a fairly tight range of 3-6 per cent, except for distressed properties or markets. By itself, this is an insufficient return given the risk. It is well below stocks and is in the historical range of what bonds have returned. However, purchasing a multifamily building is not purchasing a fixed stream of income. Rents can rise. Rising rents create capital gains and more current rental income. Combining rental income with capital gains and leverage and more projects will clear hurdle rates. Despite leverage, projects almost never clear hurdle rates without rent growth. Therefore, investors will not fund deals unless they can reasonably expect solid rent growth.

The basic multifamily acquisition is underwritten as follows. The building is acquired at a cap rate between 3-6 per cent, usually depending on prevailing interest rates. After all, buildings must produce enough income to cover debt payments.4 Then, rents are steadily increased over five years (if the market will bear it). This creates a capital gain, which is realized by a sale, usually around year five. Crucially, three factors combine to make a project clear hurdle rates: 1) Rental income; 2) Capital gains driven by rent growth; and 3) Leverage.

The going-in cap rate must be right, the rental market must be strong enough to support rent growth, and interest rates must be sufficiently low to allow for a high level of leverage.

The Economics of Multifamily Development

Multifamily development is also IRR-based, but tends to have a slightly different business model. Most developers prefer to sell as upon the completion of their project. A typical multifamily deal will be constructed at a 7 percent cap rate, then sold to an investor at a 5 percent cap rate. Completed projects can be sold for more than the cost to build them because developers bear substantial construction risk.

Some mistakenly contend that since most developers sell upon completion, they ought to be insensitive to conditions in the rental market. However, developers will only achieve their favorable exit cap rate of 5 percent if they have willing buyers. For reasons explained in the above section, investors who plan on being landlords will not buy at a 5 percent cap rate (or lower) if they cannot expect rent growth.

Thus, developers face construction risk, risks related to the softening of the rental market, and the risk of a sudden rise in cap rates linked to increases in interest rates. If any of these variables move substantially in the wrong direction, a project can fail or deliver low returns. Acquisitions, on the other hand, do not face construction risk, but are certainly exposed to softening of the rental market, or changes in interest rates.5

A Numerical Example

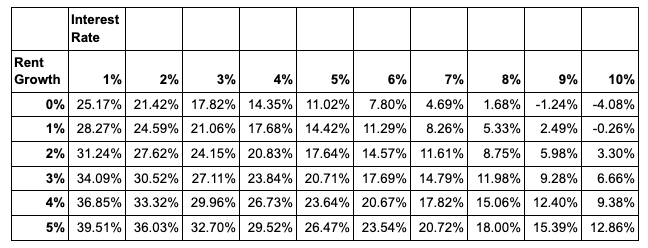

Let’s take a look at a numerical example to better understand the crucial role rent growth plays in making deals pencil out. Here, we will make some rather standard assumptions:

A 6 percent cap rate

Financing at 75 percent LTV, interest only

A five year hold period

Each cell in the table below returns an IRR given the corresponding interest rate (top row) and rent growth (first column). The IRR includes all cash flows, including the final cash flow which is the sale of the building.

For illustrative purposes, we are excluding the construction loan, construction timeline, and lease up period. These extensions in the timeline can massively reduce IRRs for ground up projects. We exclude them for two reasons. First, simplicity, but more importantly, to show that even under incredibly favorable assumptions, projects still struggle to pencil without rent growth.

Looking across the second row of the table which corresponds to zero percent rent growth, we see that the project only clears the 20 percent hurdle rate if interest rates are 2 percent or lower. Rates this low have never prevailed in the commercial real estate space. Working our way down the table, it becomes clear that when rates are between 3 and 6 percent, a typical historic range, projects really only easily clear the 20 percent threshold when rent growth is 3 percent or more. Thus, under extremely favorable assumptions, new construction projects will not clear hurdle rates without solid rent growth.

The Building Cycle and the Broad Asset Market, or Why YIMBYism Won’t Produce Affordability

Housing is a risky asset and is highly illiquid. This means investors demand a very high rate of return to build or operate it. Usually, this rate of return is significantly higher than more liquid but still risky assets like stocks. At the same time, an equilibrium exists in the broad market for assets that binds asset prices. No asset should be priced such that it provides systematically higher returns than another asset, adjusting for risk. This equilibrium condition binds housing production.

When rent growth is strong in a certain metro, it significantly raises returns to apartment buildings. These excess returns, that is, returns in excess of what the risk justifies, draw in capital and increase construction activity. Then, as new deliveries hit the market, it slows rent growth, perhaps pushing rents down. This brings the returns to apartment buildings back into equilibrium, given their risk. Capital retreats, which reduces construction. This sets up the rental market for a new period of little new construction and strong rent growth. These shifts between investment and disinvestment are governed by returns in both the real estate and the broad asset market. The industry calls it the building cycle.

These cycles can be incredibly volatile. In Austin, Texas, a massive run up in rents, combined with record low interest rates, led to record building in 2020-2022. During that period, rents surged nearly 50 per cent, only to fall roughly 20 percent as a massive flow of deliveries swamped the rental market. Conditions conducive to this level of volatility are incredibly rare. Usually, rent growth may be solid for a number of years, in the 5-8 percent range, which is enough to induce some new construction to reset the cycle. Many in the YIMBY movement mistake short-term cyclical rent declines as “proof” that building always reduces rents. While technically true, it confuses a cyclical downturn, which is tied to a readjustment in the broad asset market necessary to arbitrage away excess returns to rental housing, with a secular decline in real rents. That could only be achieved with continuous non-cyclical high levels of building. However, this could never occur via private building, since it would require investors to accept lower and lower returns on their capital as rents fell (or perhaps even negative returns).

Solutions:

Housing is expensive because it must clear high hurdle rates. Furthermore, because much of the return in rental housing is derived from capital gains and not rental income, rental housing will only be built if there can be a reasonable expectation of rent growth. This runs contrary to the YIMBY story of “building to affordability.”

Ultimately, the best way to get rents at more affordable prices is to reduce the required returns to housing so that housing can be built at lower rents or lower projected rent growth. This fundamentally means lowering the cost of capital in the housing sector. I present several solutions to achieve that end.

Harnessing US Capital Markets Through GSEs for Multifamily

Despite populist concerns about excessive consolidation in the housing sector and the supposed abuses of large corporate landlords, the development industry remains incredibly fragmented. Most apartment buildings are constructed by small to medium-sized firms, which lack access to public debt and equity markets. This means that they must raise capital on the significantly more expensive private markets, which sharply increases the hurdle rates that any potential housing project must clear.

A large, publicly traded company that could issue equity and debt on public markets would be able to raise large sums of capital at a significantly lower cost than closely held firms ever could. Theoretically, such a firm or group of firms could build housing at significantly lower rates of return than smaller companies.

For example, given the long run average of 11 percent total return in US equity markets, a publicly traded REIT6 could plausibly issue equity to finance housing projects. With the ability to tap public debt markets by issuing bonds, such a firm could construct housing at much lower rents or rent growth and still clear its 11 percent hurdle rate. This is significantly below the 20 percent baseline IRR investors in private markets demand.

To be sure, several large publicly traded REITs occasionally issue shares to finance the construction of rental housing, but it remains a genuine puzzle that these firms do not dominate the space given the tremendous advantage they have in terms of raising capital both at scale and at a significantly cheaper price.

The Federal Government could charter its own corporations, which could operate with or without a government guarantee, with the mission of building housing as a large publicly traded firm with the ability to tap public capital markets. Such a firm or firms could build housing at scale at lower rates of return (and thus lower rents or lower expected rent growth) in a way privately held firms could not, given their significantly higher cost of capital.

In essence, these firms, would enjoy a significantly lower cost of capital7 than the small and midsize ones that dominated real estate development. These lower costs could be passed on to renters as lower rents.

Using the Existing GSEs to Fund Construction

Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae have recently dipped their toes into multifamily construction lending. These products should be expanded. Crucially, the GSEs should consider enhancing leverage for the construction phase of the loan. This policy would have two important effects. First, it would reduce the amount of equity capital that developers would need to raise. Construction loans typically require 60 per cent LTV8, which means that developers must raise significantly more equity to build than to simply acquire existing housing, which typically allows for loans up to 80 percent LTV. Equity capital is hard to raise and is more costly. Secondly, low LTV ratios mean that projects as a whole must produce much higher returns so that the equity slice of the capital stack clears hurdle rates. By offering more leverage to developers, they can take on lower-returning projects and still clear hurdle rates demanded by equity investors.

Higher leverage loans could be offered with or without affordability covenants. Because of the higher leverage, return on equity would be enhanced, which might allow for some restrictions on unit rents. Mathematically, lower potential rental income will reduce the sales price of the project somewhat, which will compress gross margins. However, since the equity slice of the capital stack is only 50 per cent as big, return on equity may rise or stay constant. This would allow projects to go forward at rents lower than otherwise would be necessary to clear hurdle rates.

This program could be run so that it still generates a profit for the government and is thus not a giveaway to investors. These loans would earn interest and therefore generate a return, and the GSEs could ensure that the rates charged on these loans exceeded default costs so that the program was self-sustaining.

Municipal Housing Stakes and Fee Timing

Many states and municipalities have started housing accelerator funds to help finance new construction. These funds usually take an equity stake in the project. The goal is not to produce publicly-owned housing. Like privately financed deals, the project is sold to investors upon completion. However, by providing equity at a lower required return, these funds accelerate housing production. It is also important to note that municipal governments might have sound reasons to accept a lower return than a private investor. New development grows the property tax base, which is a permanent revenue stream and if considered, would substantially increase underwritten returns.

For states or municipalities that rely on high development fees, adjusting the timing of the payment of fees (if they cannot be reduced) can significantly increase IRRs. This works in two ways. First, it synthetically increases leverage because fees do not need to be paid out of equity. Second, by delaying the collection of the fees, it lowers their present value and thus raises IRRs. Municipal governments should highly consider allowing fees to be collected via a lien against the finished project, which is junior to other debt but senior to equity. This would not trouble lenders, since they remain in first position.

Conclusion:

Housing is a basic need. However, housing production is constrained by its risk and the relative risk-adjusted returns to housing in the broad asset market. Housing is illiquid and risky, thus it has a high cost of capital. Housing cannot truly be built at lower rents unless other factors can keep returns from falling. The best way to achieve this is to address housing’s high cost of capital by changing how housing is financed. Creating larger development firms with lower costs of capital, expanding lending from the GSEs, or changing the timing of fee, are promising solutions along these lines. Only by fixing housing finance can we truly address long-run affordability.

An IRR can best be thought of as an adjusted annual rate of return adjusted for the timing of cashflows and deployment of capital during a long term business project.

Not in My Back Yard

$500,000 divided by 0.5 is $10 million.

Typically, lenders require that income covers 125 percent of debt service. Thus, the real estate sector is highly sensitive to changes in interest rates.

Even if their loans are fixed rate, increases in interest will reduce building values.

Real Estate Investment Trust

With or without a government guaranty

Loan-to-Value

This was a joy to read and I learned a lot. Thanks! Two high level comments.

First, you argue that upzoning won't be all that helpful because the real problem comes from the capital markets side, and the demand from investors for high IRRs. But don't the high IRR requirements for real estate development result partly from local land use regulations that add whole new dimensions of delay and risk?

As I see it, the right kind of land use reform (see my upcoming essay) would help unlock the financing because there wouldn't be so much red tape, waiting for government permission, and running risks that you'll never get it.

Second, you recommend new federally chartered agencies, expansion of the GSEs' scope of practice, and/or municipal real estate finance interventions similar to what the GSEs do, as a way to lower the financing costs of housing. Maybe-- but the GSEs or similar entities are rather odd and under-theorized, and open to the critique of being inefficient central planning that socializes risk.

I'd be interested in a Substack post by Mike Fellner entitled "The Case for the GSEs," or something like that. :) The operations of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac don't map cleanly onto the core arguments economists make for why government should have a role in the economy. They're not performing a basic judicial/property rights enforcement function, even if there's a bit of adjacency. They're not doing monetary policy, even though there's some adjacency to financial regulation. They're related to meeting a basic human need (housing), yet they're not a welfare program. They're not exactly/explicitly a subsidy program-- and yet the implicit government guarantee that became explicit in 2008 argued had a big macroeconomic cost. Should the GSEs exist at all? Why? What's the theoretical case?

Two arguments come to mind for me:

1. They're a mechanism for subsidizing homeownership because homeownership (arguably) has positive externalities.

2. Some kind of economies of scale in housing finance are being secure through government leadership... but does that even make sense? I can't quite wrap my head around the model.

My concern is that interventions on the housing finance side, to reduce the IRR required for multifamily housing to clear investment hurdles, would just socialize more risk.

I found this essay enlightening. Where I focus on the demand side of housing finance, this sheds light on the supply side, and I think the two pieces complement each other well.

It’s interesting that it really does come down to a supply-demand issue, just not of housing units themselves, but of finance.

In that light, my proposed transfer surcharge, which limits credit available for mortgage principal and redirects it toward returns on new construction, ends up addressing both sides of that imbalance.