Housing Policy Should Prioritize the Middle Class | Part 1

Rather than subsidizing the outcomes of failure, policy should invest in the inputs to success

Demographic Deferral

Housing policy in America optimizes for the wrong people; right now it overwhelmingly serves two groups: the wealthiest 10%, who benefit from the preservation of their asset values, and the poorest 10%, who receive the bulk of subsidies. The vast majority of households in between — especially young would-be homeowners — have been structurally ignored. The Boyd Institute believes this is a mistake and advocates for a housing policy that puts young families first.

We have chosen to plant our flag on the hill of arguing in favor of the interests of the young, middle-class professional with plans of parenthood because this cohort forms the backbone of society — and it is in the direct material, as well as moral, interest of America that they are able to set out on productive and fertile lives. That they have been stumbling in recent years, most notably in their decisions to postpone or even totally eliminate family formation, is of extreme, literally existential, importance.

Much of the discussion around housing policy operates under the polite fiction that it is possible to benefit one group without harming another. But the truth is that in an environment where budgetary support for housing is limited, all policy involves tradeoffs. Given the existence of these tradeoffs, policymakers have chosen, unsurprisingly given the moral tenor of politics, to advocate primarily for the interests of the bottom decile of rent-distressed households. Young, upwardly-mobile people are not the ones who need financial help the most; they can always make sacrifices that the less-fortunate cannot.

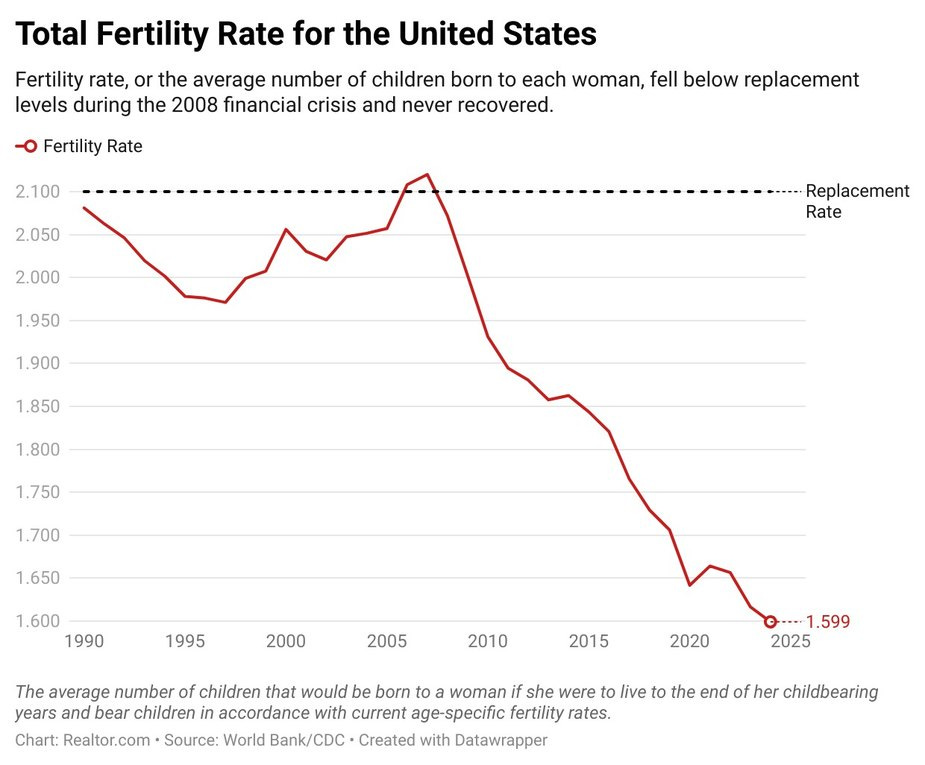

But these sacrifices come at a serious social cost, which can be seen for those who are willing to look. Youth mobility has reached the lowest point in recorded American history, the average age of a first marriage continues to climb, and the fraction of children born to mothers under 30 has fallen from more than 70% in 1990 to less than half today.

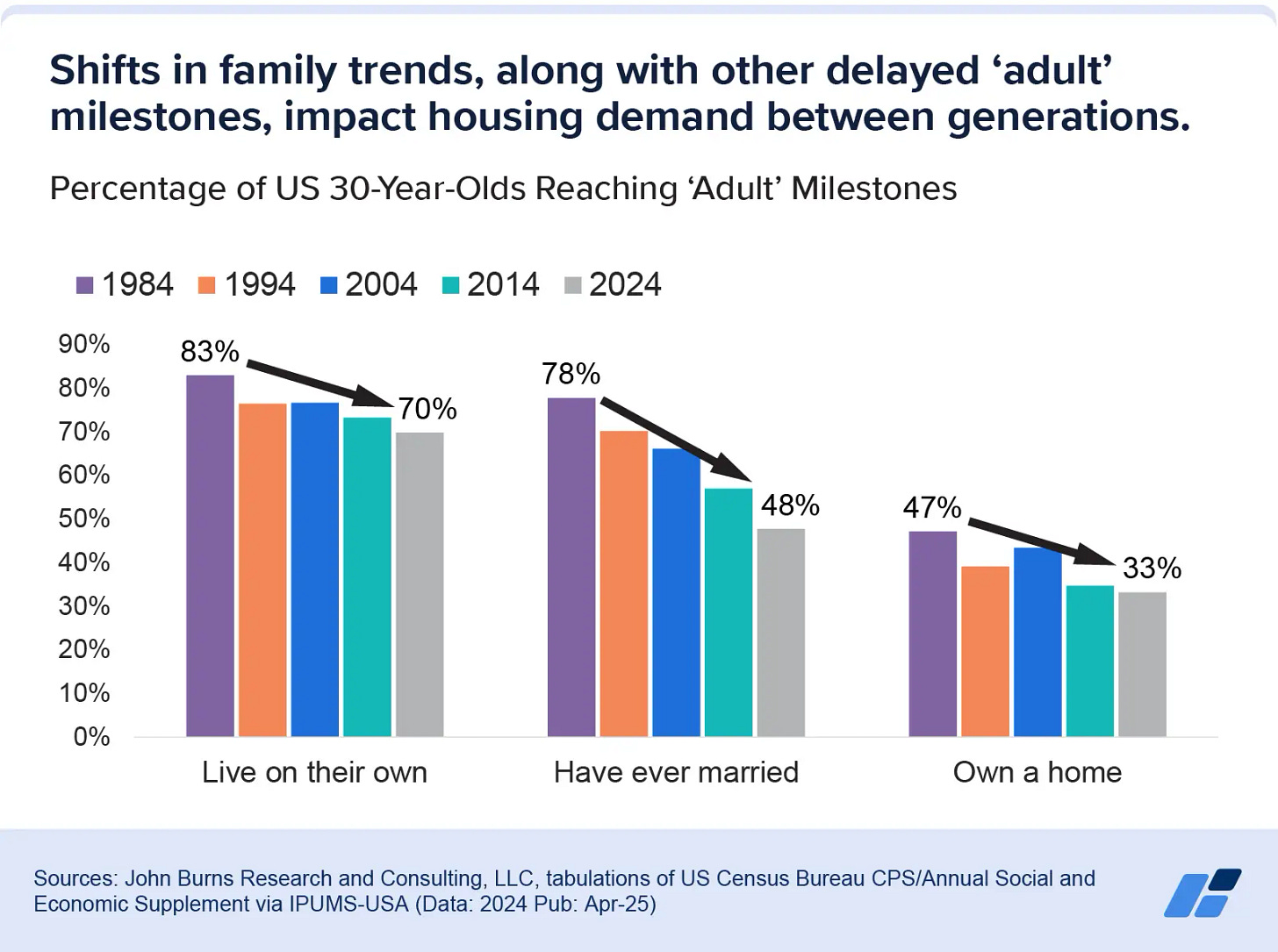

Compounding this is the fact that young, upwardly-mobile adults have been largely boxed out of the housing market. In 2025, the median age of a US homebuyer was 56 years old, up from 31 in 1981. And from July 2023 to June 2024, people between the ages of 26 and 44 accounted for only 29% of all home purchases, compared to 42% for the Boomers. Indeed, fewer and fewer are reaching ‘adult’ milestones by the age of 30:

However, even if these young adults do not “need” the support — they can always, say, borrow from their parents or run up a credit card bill to make ends meet — it is exactly here that from an economic growth perspective, the highest ROI exists. In this sense, support for young adults who have formed families (or intend to) is truly an “investment” which will pay for itself1 — in contrast to other forms of welfare where although it is in the moral interest of society, there is no expected return of broad-based improvements in material conditions.

In short, Boyd’s insight here is that we must stop pretending tradeoffs away and instead make them explicit and defensible. The tradeoff we propose is straightforward: optimize housing policy for household security, family formation, and clustering of productive human capital among the middle 80% of earners, rather than for poverty management of the bottom decile and preservation of the top decile’s capital gains.

What we are calling for is a fundamental inversal of the way politics has traditionally been done. Rather than subsidizing the outcomes of failure, policy should invest in the inputs to success.

This the first in a series of four articles where we will outline our arguments for what we believe should be prioritized — family- and household-formation — from a policy standpoint. After having articulated where the problems lie and why current housing policy is suboptimal, we will reveal our full-scale reform proposals and begin the arduous process of advocacy.

We have no illusions that this will be an easy fight; prioritizing families means moving away from the business of poverty management — a business with many powerful defenders. But this is a fight worth having if America is to thrive.

The Housing “Crisis”

The market is clearing

When you begin trying to ask the question of what exactly people mean when they talk about a housing “crisis,” as we have in all of our interviews with academics and experts, the first thing you will notice is how many different possible answers there are. Explanations range from stories of spatial misallocation to questioning the entire premise. This is not surprising since the housing market exhibits a high degree of distributional symmetry, where for every loser there is a winner on the other side of the ledger.2

To see just how symmetrical housing is you only need to look at the diversity of definitions for the housing “crisis.” It can variously mean: (1) insufficient homeowner asset appreciation for current owner-occupiers; (2) inadequate low-income affordability; or (3) insufficient housing access for young, middle-income professionals seeking to form households and families. It should be obvious that it is definitionally impossible to solve all of these “crises”.

For example, when home prices rise, the capital gains typically accrue not to “rent-seeking institutions” but to ordinary people — incumbent homeowners with accumulated home equity serving as their de facto retirement asset; mom-and-pop investors with modest rental portfolios. Rent control offers another clean example. Economists have long shown that while it protects a fortunate subset of tenants, it simultaneously reduces mobility, discourages maintenance, and deters new construction. In other words, the very policy that secures stability for some necessarily erodes opportunity for others. Economists describe this zero-sum logic as Pareto efficiency: a state where, under spacial constraints, no policy change can make someone better off without making someone else worse off. Uncomfortable as it may feel, the US housing market is indeed in a Pareto-efficient state.

However you look at it, the fundamental fact that the market is ultimately clearing, remains; every dwelling finds an occupant at some price. Sure, shortages may form in localized pockets. Notably, Baum-Snow and Han (2024) provides empirical evidence for this.3 But in the end, on a city-by-city and aggregate, nation-wide basis, the necessary quantities of housing do in fact get built (and bought/occupied) where and when permitted.4

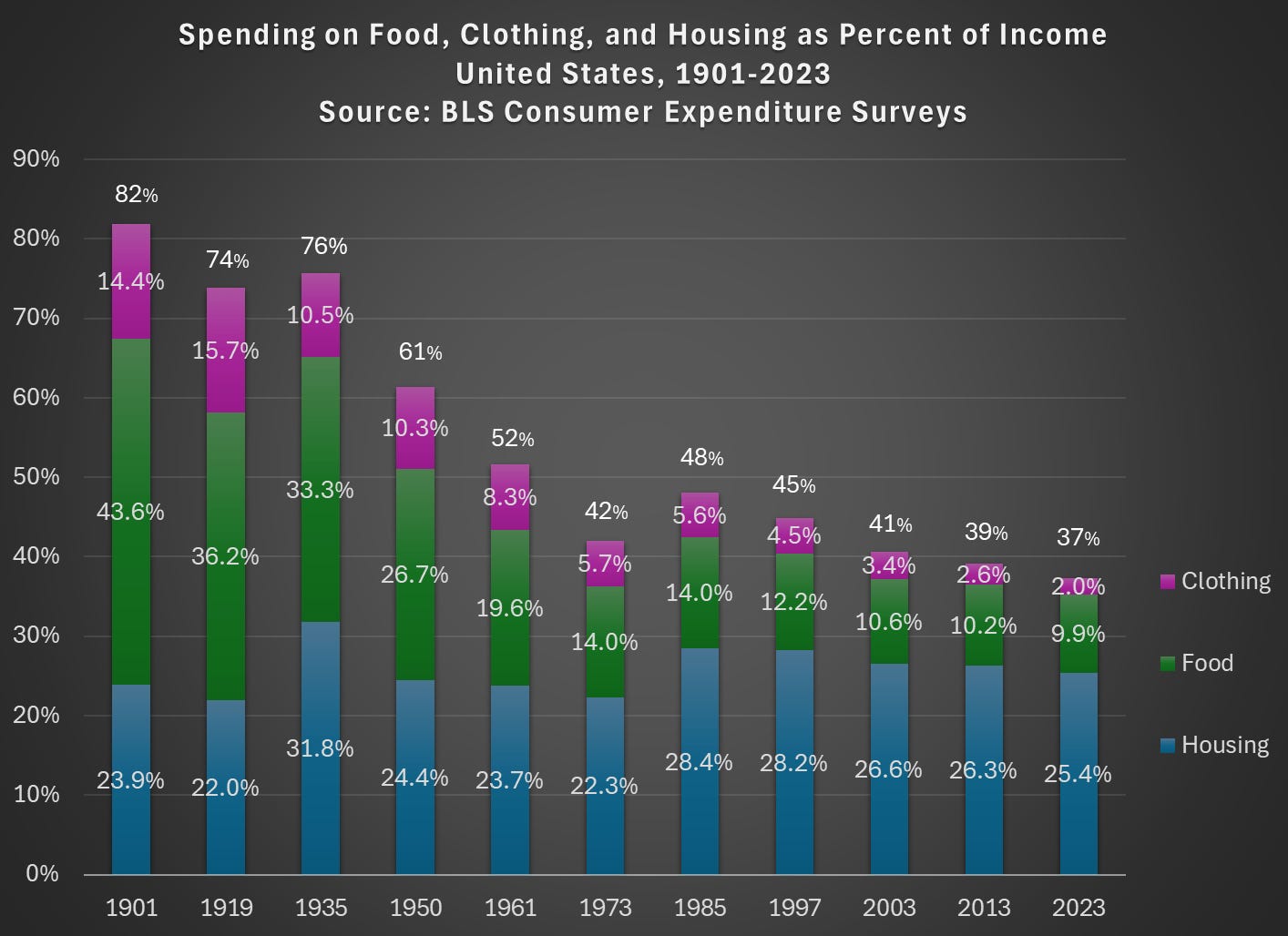

One way to visualize this fact is in the remarkable degree of stability in the percent of household income people spend on housing.

But…

The aggregate story is conflationary, and reading into it too narrowly risks masking acute dysfunction at the city or neighborhood levels. The real “crisis,” according to NYU Stern professor Arpit Gupta, is not about people being unable to afford a roof but instead about access: can people live where they want, near jobs, schools, and amenities?5

This account of the housing “crisis” — advanced by the YIMBY movement and mostly focused on state and local policy — holds that zoning and related land-use regulations function as an implicit tax on housing production in desirable urban areas, creating shortages within “superstar cities.” By distorting the supply response where demand is strongest, these localized supply constraints push construction toward less desirable, suboptimal locations. The YIMBY claim is thus both about affordability and allocation: supply constraints raise prices and rents in constrained neighborhoods and, by diverting people and units away from high-productivity areas, produce spatial misallocations of housing and human capital.

So what does the evidence say? This premise is supported by a large body of empirical literature; easing exclusionary rules (e.g., minimum lot sizes, parking mandates, discretionary review) and streamlining permit approvals, according to the prevailing consensus among researchers and economists, would improve the return profile — “the economics,” or marginal profitability — of housing production for developers such that supply could more-elastically meet demand where it is pent-up most.

Still there are serious limits to the YIMBY story. The immediate impacts of upzoning and deregulation will likely be muted. Indeed, structures were built — often along the urban fringes, away from the job centers — and since redevelopment is rarely economically feasible (see Rollet 2025), we are likely “stuck” with the housing stock we have. Given that housing construction starts are — almost by necessity — induced by rising rents, no city is likely to experience the purported affordability or spatial allocation benefits of pro-YIMBY legislation until there is a new demand shock to elicit a supply response. Building into falling or flat rents simply does not occur, even if upzoning allows for it.6

In other words, just because new forms of housing become legalized does not mean there will be an immediate uptick in construction — and even if lifting supply constraints may be necessary in the long run, it is unlikely to be sufficient to produce short-run affordability.

Putting families first

So if there is no perfect solution to this “crisis” — or even a perfect definition — it begs the question: what does the optimal housing market actually look like? Well, it ultimately depends on the group we wish to optimize for. Optimal for an old incumbent fundamentally looks different than optimal for a young family who rents, since their interests are in many ways at odds. However, even if there is no way to make everyone better off without harming anyone, it is still possible to make broader claims about what basket of housing policies would be best for “society” (or to use the language of economics, what policies would be “welfare maximizing”).

Young, educated professionals are not needier than the poor, granted. But their clustering yields positive externalities — innovation, civic engagement, tax revenue, and fertility (organic population growth) — that ripple outward through society. Subsidizing this simply makes sense, especially given that the toll of high housing costs are already clearly pushing down fertility rates.

A recent paper — Couillard (2025) — shows this empirically. According to the study, the rising cost of housing was responsible for 51% of the total fertility rate decline between the 2000s and 2010s, and if housing costs had remained flat after 1990, there would have been 13 million more children born in the US by 2020. “Housing and fertility are jointly determined because large and small families sort into different locations based on the number of children they have — or want to have — and housing costs,” the author said in an interview, adding that “a maximalist housing policy, one that aggressively expanded supply to prevent costs from rising, could have solved the majority of the fertility problem.”

When you take everything together a clear picture emerges: housing is not a side constraint; it is one of the central margins along which Americans are choosing fewer children, later marriages, and weaker attachment to high-productivity places. If you want more families, there is no way around the housing market.

It is at this intersection of family- and household-formation that we firmly believe the case can be made for prioritizing the needs of the young, upwardly-mobile housing cohort, who has the potential to more-than recoup any costs through the economically multiplying effects of future income and children.

Today’s housing policy largely does just the opposite: it identifies poverty, codifies it, and then subsidizes it. The apparatus — means-tested subsidies, income-restricted zoning, bureaucratic gatekeeping — is designed to classify people by need rather than potential. In turn, the outcomes are precisely what one would expect: less housing, higher costs, and a systematic exclusion of the productive middle class.

A family-first housing policy regime takes these outcomes seriously and works backwards. Instead of treating all households as interchangeable units sorted only by income, it asks where a marginal dollar or regulatory change does the most work over the long run. The answer, empirically, is not at the very end of the life cycle — and it is not in preserving incumbent windfalls. It is in lowering the cost of securing adequate housing to form a family in one’s late twenties and early thirties, in the places where skills and opportunity concentrate.

In practice, this implies three broad design principles we will return to in later installments. First, target support at life stages and events that have large downstream effects: household formation, childbirth, and relocation for work. Second, ensure that the kinds of units families actually need — larger rentals, starter homes, and stable middle-market stock — can be built and preserved at scale, rather than treating them as an afterthought to poverty programs and asset-preservation politics. Third, focus on access to high-productivity metros and neighborhoods, so that young families are not locked out of the very places where their human capital and their children’s prospects would be highest.

In parts two through four of this series, we will outline our arguments and preferred policies in much more detail. But if you walk away from this article with one thing it should be this:

The generation of people who will eventually inherit this country are being screwed over, and unless something is done to reverse this we, as a society, face the potential for actual disaster. For the last 60-odd years, America has forgotten the simple fact that for our country to survive each generation must successfully pass through the various stages of life; the fact that young families now increasingly find it impossible to set out and begin their life is unsustainable.

It not only threatens the demographic and economic stability of our country, or the tax basis which funds other noble goals including the alleviation of poverty — but democracy cannot survive if the citizenry are not actively bought in. Increasingly, our policy has left the young, middle-class family out in the cold.

Research on Danish administrative data found that 27 percent of each unit of parental housing wealth gains during early and middle childhood is transmitted to adult children’s long-run wealth accumulation, with effects particularly pronounced when housing wealth increases occur between ages 6 and 11.

Of the ~132 million US households, ~87 million are homeowners while ~45 million are renters.

Their findings show a high heterogeneity in supply elasticity — from approximately 0.2 to 0.9 across census tracts — indicating that construction tends to occur in suburban or exurban tracts where regulatory and physical constraints are looser rather than in central cities and high-value neighborhoods.

The Louie-Mondrago-Weiland (2025) SF Fed working paper has ruffled some feathers among purveyors of the housing supply-side orthodoxy. It showed, very basically and even intuitively, that the established measures of zoning rules and land use restrictions — “supply constraints” — do not actually explain house price and quantity growth across US cities. That is, in econ-speak, that supply elasticities, or the responsiveness of growth in housing supply quantity to changes in price, do not meaningfully differ from one city to the next. Contrary to the consensus view, the paper instead finds that higher income growth alone predicts the same growth in house prices, housing quantity, and population — regardless of a city’s estimated housing supply elasticity. The authors interpret their finding of housing supply elasticity invariance as calling “for a reevaluation” of “policy prescriptions that hope to improve housing affordability primarily through the relaxation of housing regulations.”

Or as we might ask, can people have children and form families?

Additionally, land-use regulations emerged endogenously over the course of decades and in many cases probably represent an efficient set of restrictions (at least for incumbents); after all, local communities often resist top down interventions for a reason.

Nothing but full-throated support for this line of thinking.

"the interests of the young, middle-class professional with plans of parenthood because this cohort forms the backbone of society"

I can't think of a better representative group. I'm a bit uncomfortable, however, with the idea (and maybe I'm just reading too much between the lines) that there are big _necessary_ tradeoffs between the interets of this group and others. Better (less restritive) land use policies, up-to-date building codes, better policing, better public schools are definitely good for young middle class professionals but do not harn the "rich" or the "poor."