Weekly Roundup #12

Housing | Aesthetics matter, the impact of supply constraints on intra-city prices, failed policy quick fixes, & more

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Welcome back to Boyd’s roundup series. We hope you all had a lovely Thanksgiving — and a relatively seamless and painless experience to the extent you braved traveling by plane!

Earlier this week, we published the third part of our series on why housing policy should be optimized for young, middle-income households. This article laid out the various existing suboptimal policy regimes at the federal, state and local levels.

In the next and final part of this series, we are excited to finally be laying out our specific policy proposals — so keep an eye out for that! Now, for this week’s roundup we have…

Newsflow:

On Washington’s misguided obsession with subsidizing demand rather than supply

On a marked increase in delistings and the growing chasm between housing market buyers and sellers

Academic research:

On an under-appreciated reason why voters oppose dense new housing, especially in less-dense neighborhoods: they think it looks ugly

On how supply elasticity can shape why neighborhoods within a single city experience very different price changes

Additional reading:

On the failed quick fixes surrounding local policymakers in SF and NYC villifying RealPage and Airbnb

On how the “housing crisis” is a global phenomenon, not limited to the US market

NEWSFLOW

Boosting Demand Won’t Fix Affordability

WSJ Opinion | David Hebert

When Americans can’t afford something, Washington loves to help buyers and ignore producers. Politicians might feel as if they are improving affordability, but the strategy creates a vicious cycle: lawmakers subsidize purchases, watch prices rise, blame corporate greed, and then subsidize purchases even more to compensate. The American taxpayer is left funding the entire cycle.

The Trump administration is using the same strategy to address housing affordability. Longer-term and portable mortgages won’t solve the housing supply deficit. This demand-side stimulus will inevitably end the same as the healthcare strategy: higher prices, encouraging more bailouts from the American taxpayer.

The government fueling demand will always raise prices. The only question is whether politicians will stop pretending otherwise—and how much Americans will pay until then.

US Homesellers Pull Stale Listings Off Market as Interest Fades

Bloomberg | Prashant Gopal

Nearly 85,000 sellers removed their properties in September, the highest number for that month in eight years, according to Redfin. The number of stale listings — those sitting on the market for 60 days or more — jumped to the highest level for any September since 2019.

The housing market is weakening as economic uncertainty and affordability concerns keep buyers on the sidelines, even as available listings grow. That’s causing many Americans to stay in their current homes, rather than settle for lower offers.

“Buyers and sellers are living in different worlds now,” said Chen Zhao, head of economics research at Redfin. “Buyers are demanding that prices need to be coming down, but sellers are still expecting prices to stay resilient and to continue growing. Sellers are not liking where market clearing prices are.”

ACADEMIC RESEARCH

How Sociotropic Aesthetic Judgments Drive Opposition to Housing Development

Broockman, Elmendorf, and Kalla (2025)

The theories entailing homeowners seeking to protect property values and NIMBYism — neighbors fearing local nuisances (traffic, parking, etc.) inundating their communities — have clear merits. But there are gaps. This paper proposes an additional reason for why voters oppose the construction of new housing: sociotropic aesthetic judgments. That is, voters forming automatic assessments about whether a building is visually appealing or “fits in.”

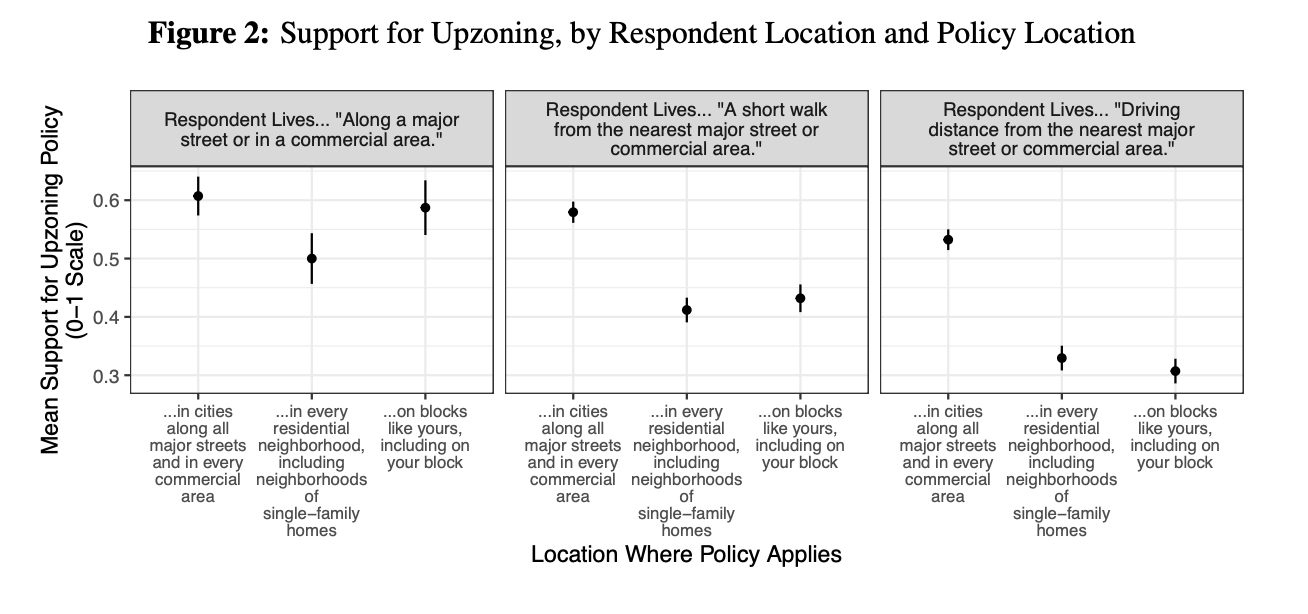

Existing theories predict homeowners in dense areas should be the biggest opponents of more density in already-dense areas — i.e., it’s their backyard. But homeowners in corridors are actually most supportive (relative to renters) of upzoning of corridors!

The paper’s authors think two things are going on here: (1) People self-select into neighborhoods that match their aesthetic tastes — if you live in density, you likely have a “taste” for it; and (2) Voters prefer development that “fits in” with the existing built environment

They found widespread support for 5-story apartments along commercial corridors (where they fit), but sharp opposition in single-family neighborhoods (where they clash):

This may not only explain the political success of “commercial corridor” upzoning policies (like CA’s AB 2011), but also that “ugliness” actually matters a lot compared to other concerns.

The paper’s results do in fact show that perhaps part of why single family homeowners oppose local density isn’t NIMBYism, but a widely shared view density should go in already-dense areas. Furthermore, its results confirm that both visual appeal and fit in context powerfully drive support for housing, and seemingly far more than affordability concerns. These judgments are sociotropic: voters didn’t just oppose ugly buildings on their own block; they opposed policies that would allow “ugly” buildings anywhere. That is, just as people support redistribution for the “greater good” they support aesthetic regulation for the “greater good”.

The policy implications?

Design matters — form-based codes might reduce political friction

“Missing middle” housing/upzoning is often more politically feasible than general upzoning

A Revisit of Supply Elasticity and Within‑city Heterogeneity of Housing Price Movements

Ren, Wong & Chau (2023)

This study challenges a common assumption in housing economics that all neighborhoods within the same city function as one integrated market where people can easily substitute one area for another. Most research has focused on how supply constraints differ between cities, but paid little attention to why neighborhoods within a single city experience very different price changes.

Using Hong Kong data from 2003-2018, the paper shows that what matters most for a neighborhood’s price growth is how much new housing can be built there — not what happens in nearby areas. In fact, when supply increases in one neighborhood, the effect on adjacent areas is surprisingly small (only about 1/10th as large)! This finding suggests that neighborhoods are more separated from each other than economists typically assume.

The authors propose new ways to measure how interchangeable neighborhoods really are, accounting for differences in available land and how prices move together. Their work implies that citywide housing policies might not work as expected; instead, policies should be tailored to the specific constraints of each neighborhood to actually affect local prices. This might explain why upzoning doesn’t always usher in a wave of new construction.

ADDITIONAL READING

There’s No Quick Trick to Solving the Housing Crisis

The Rebuild | Tahra Hoops

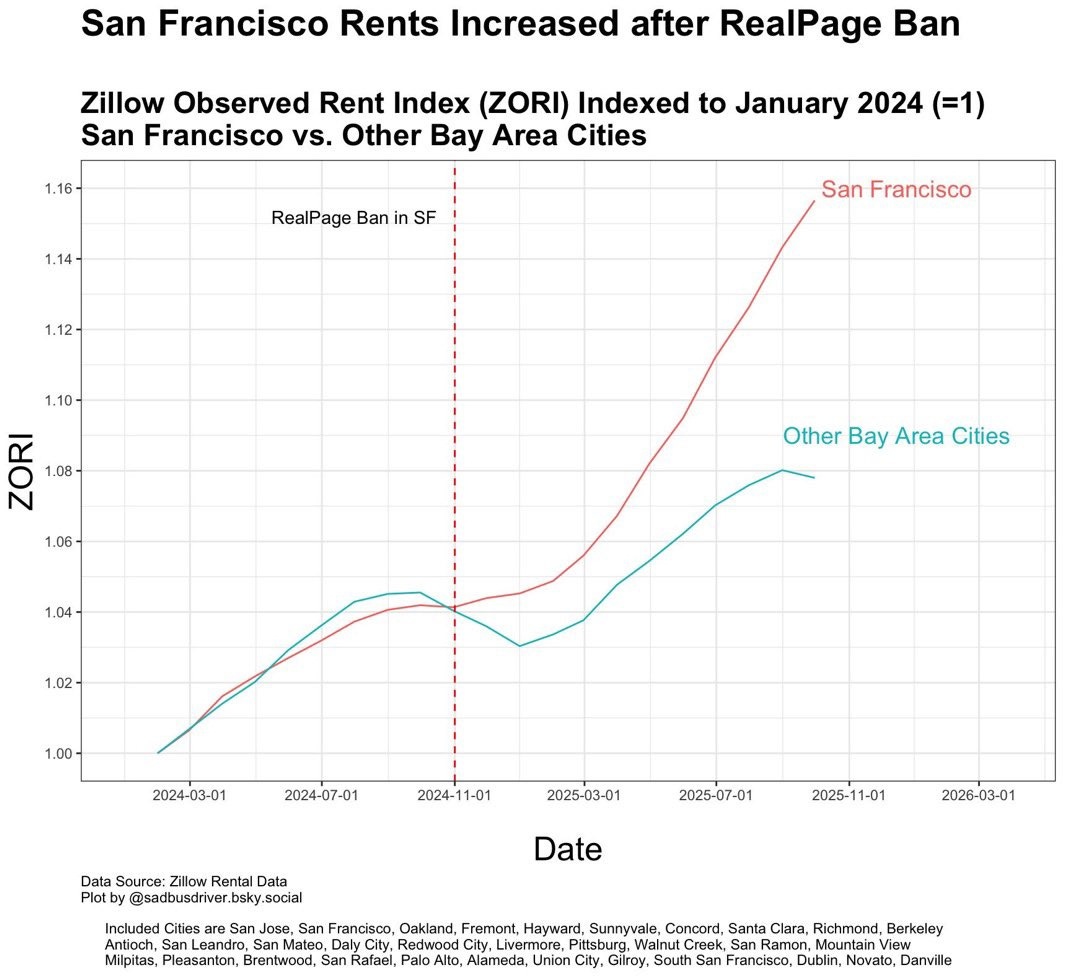

In 2024, San Francisco lawmakers set their sights on algorithmic rent-setting software, blaming it for collusive pricing and inflated rents. The city’s Board of Supervisors passed the nation’s first ban on the sale or use of such “algorithmic devices” for rent pricing.

By outlawing software like RealPage’s YieldStar, officials hoped to remove those “coordinated” pricing signals and slow down rent hikes. The hoped-for rent relief never materialized. In fact, San Francisco rents continued climbing after the ban.

Notably, one intended effect of the ban was to discourage landlords from holding units vacant for higher prices. While Peskin argued the software had “intentionally kept units vacant,” data on SF rental vacancy rates post-ban did not show a marked change (vacancy remained low, around 5% or less). In essence, landlords continued to benefit from a very tight market.

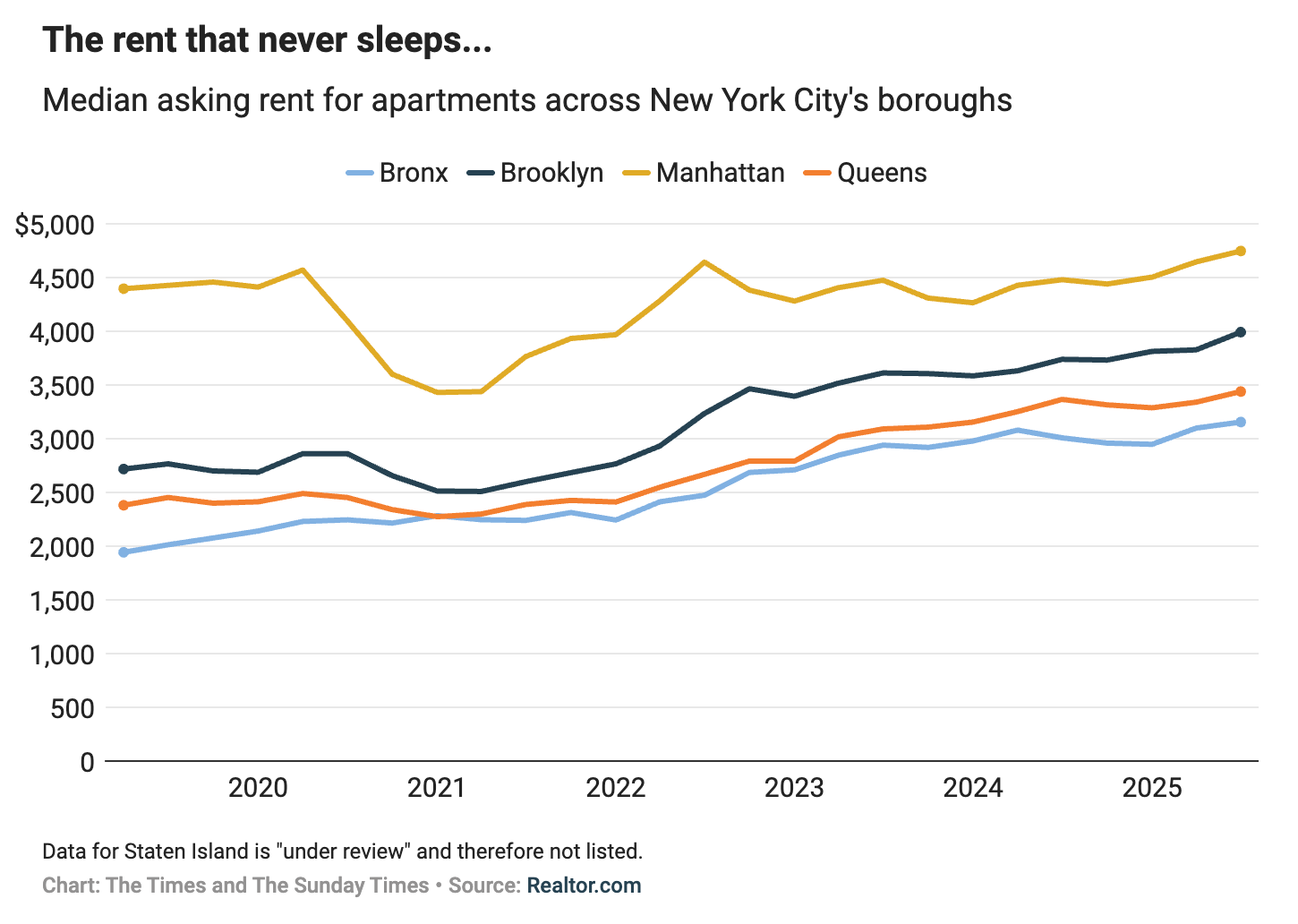

Across the country, New York City took its own swing at solving housing scarcity by cracking down on short-term rentals. Local Law 18, implemented in September 2023, banned most whole-home Airbnbs. Officials promised that removing tens of thousands of listings would return those units to the long-term market and ease rents. That didn’t happen.

While Airbnb listings plummeted (down 90%), the number of units converted to long-term rentals was negligible—just 1,400 out of more than 3 million housing units. And instead of renters benefitting, hotels did: average nightly rates surged to hitting $417, a night, this time last year. Hotel occupancy rates hit 91%, far above the national average.

It’s no coincidence hotels benefited so handsomely. The hotel lobby not only cheered the Airbnb ban – it has actively worked for years to constrain New York’s supply of accommodations. The law removed an important income stream for thousands of middle-class New Yorkers, many of whom used Airbnb to make ends meet. Small businesses in Brooklyn and Queens also suffered, reporting steep drops in customer traffic now that tourists were pushed back into Manhattan hotel zones.

Villians Are Easier Than Solutions

There is no quick trick to solve a housing crisis. The pattern we see with RealPage and Airbnb bans reveals something deeper about how we approach policy: we’re often more comfortable identifying villains than confronting the structural scarcity that creates the problem in the first place.

Until our leaders muster the will to build our way out of the shortage, any supposed quick fixes will continue to disappoint.

Why are home prices growing so much faster than incomes?

Home Economics | Aziz Sunderji

The most common answer—across academia, social media, and traditional media—is also the most intuitive: housing supply has not kept pace with demand; a uniquely American opposition to housing development (NIMBYism) has made building dense housing illegal in most parts of our expensive cities.

The near-consensus solution flows easily from this premise: if we want more affordable homes, we need to remove zoning and other regulatory impediments to building. Unshackled from these constraints, housing supply would soar, returning prices to more sensible levels.

This explanation is satisfying, both for its simplicity and because it provides us with a clear target for our ire (NIMBYs). But it does not hold up to empirical scrutiny.

Most obviously, home prices have risen faster than incomes not just in the US but around the world—and, importantly, in places that have very different approaches to zoning. In fact, housing has become more unaffordable in most major economies at a faster pace than here in the United States. This is shown in chart 1, which depicts the price-to-income ratio across countries (the ratio is rebased to 100 in 2004)

Maybe 2004 doesn’t quite capture the deterioration correctly—perhaps we need to benchmark from an earlier or later period?

The heatmap (chart 2) shows countries ranked by the change in affordability benchmarked over various time periods. A vibrant blue cell means that, for the country in that row, home affordability has deteriorated more than in other countries, when measured from the year shown along the top axis.

Housing in most countries has become more expensive relative to incomes, and this ratio has risen faster elsewhere than it has in the US, measured over most periods in the last 50 years.

The countries where home prices have rapidly become less affordable range from Canada to Switzerland to Norway, Australia and New Zealand, Belgium, Portugal, Germany, and Denmark. These countries have a wide range of approaches to zoning.

Germany, for example, does not have a class of zoning for single-family residential—they are grouped with small multifamily and townhomes. Portugal allows apartments “as of right” in many zones and has few exclusionary categories. The Scandinavian countries have far more state land and build far more mixed-use buildings than we do in the US.

Zoning reform is a local answer to a global phenomenon and can, at best, be a necessary but not sufficient explanation for the global housing crisis.

“the number of units converted to long-term rentals was negligible—just 1,400”

—>I clicked on the link there but I understood the numbers differently than you did here.

From the article: “under the new law, more than 1,400 property owners across the city have notified the office that they prohibit short-term rentals in their buildings.”

From what I read here, this doesn’t even mean they are converting their units for long term rentals, just that they are no longer using them for short-term rentals.

Either way, clearly the law didn’t lead to an immediate spike in long-term units available for rent.

Brilliant synthesis here, especially the research on sociotropic aesthetic judgments. What strikes me is how this reframes the entire NIMBY debate. The conventional wisdom holds that homeowners oppose density to protect property values, but Broockman et al. show that people in already-dense corridors actually support further densification while those in low-density areas oppose it everywhere, not just locally. That's a fundamentally different political dynamic. It suggests the opposition isn't primarily self-interested rent-seeking but rather a genuine (if problematic) preference for visual cohesion. The policy implication is subtle but important: form-based codes and context-sensitive design might reduce resistance more effectivly than arguing about affordability. Though I wonder if this aesthetic conservatism is itself partly endogenous to decades of exclusionary zoning that trained us to see density as visually jarring.