Why Rational Policy Should Invest in Young Families | Part 2

The demographic dividend imperative

In part one of this series we detailed in terms of first principles why it is in the social, moral, and economic interest of the country for housing policy to target helping the middle 80% of the household-income distribution. This article, part two, substantiates our claims for why federal, state, and local governments should prioritize young families when crafting housing policy. Specifically, it is our view that young American families present the best ‘returns-to-society’ profile for the following three reasons:

Due to the nature of how fertility decisions are made, in particular the centrality of housing costs for middle-income families, it is this cohort for whom housing subsidies would provide the largest dollar-for-dollar lift on fertility rates;

Asset accumulation and compound interest combine with family level effects in such a way that a dollar of assistance to a young household pays outsize dividends to society; and

To the extent that positive “agglomeration effects” exist in urban areas, they are primarily concentrated in young, middle-class residents such that housing policy targeted at this cohort may produce the largest socioeconomic surplus.

Claim 1: Middle-income household fertility is the most responsive to “child-related,” predominantly housing, costs.

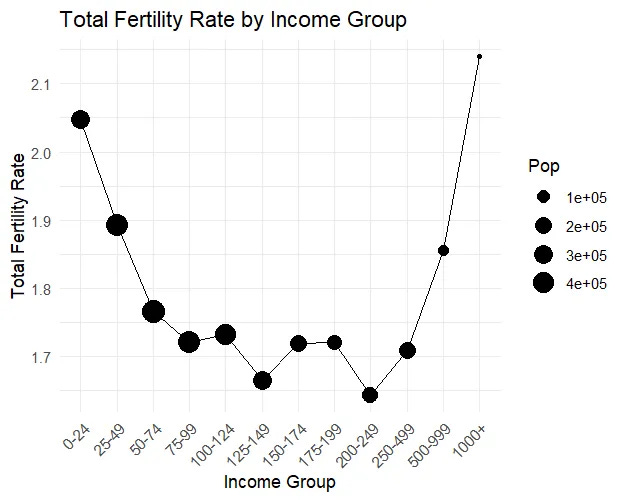

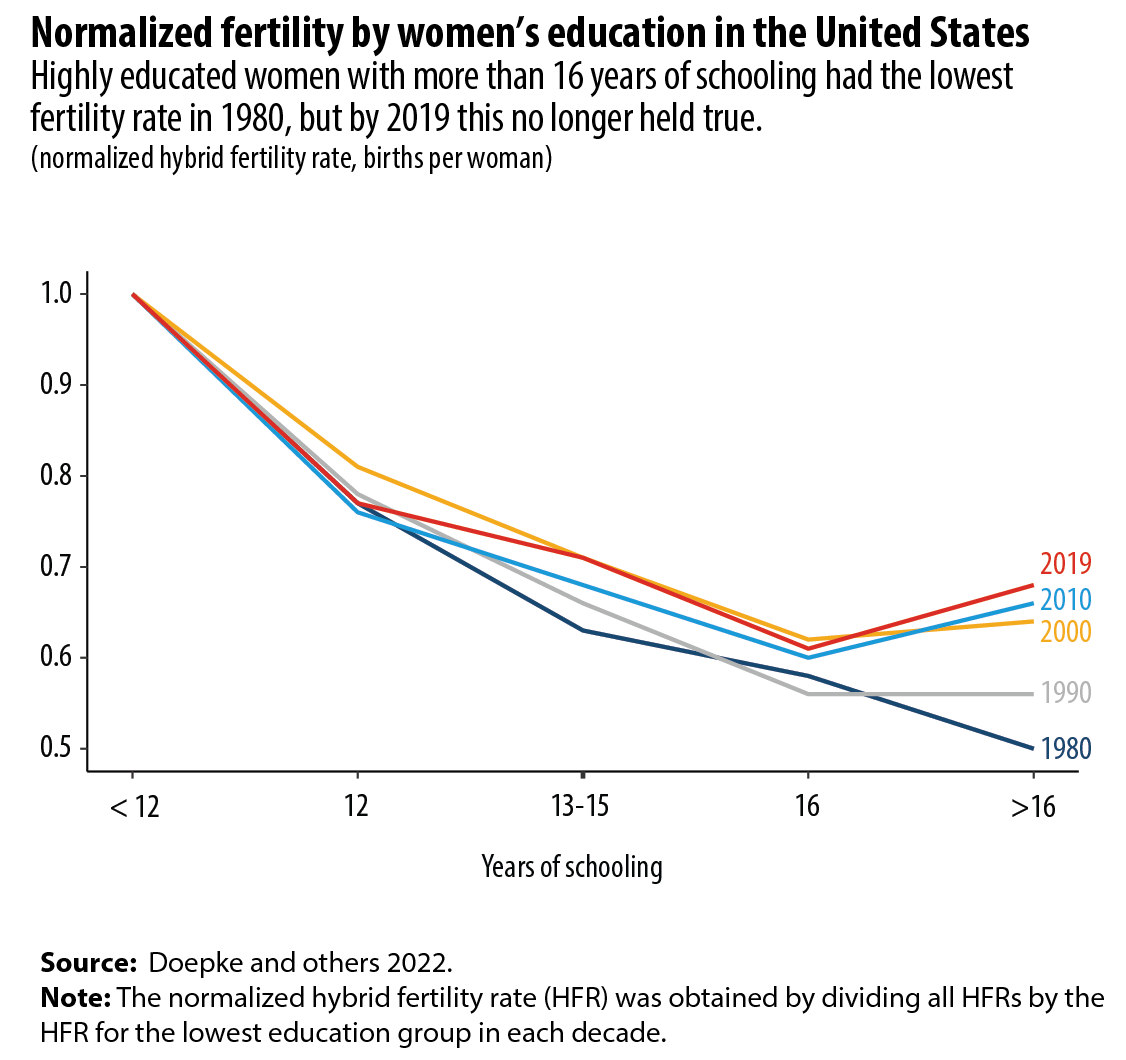

Central to this claim is the shape of fertility in the modern developed West. Historically, the relationship between income and fertility since the industrial revolution has been straightforwardly negative — wealthier families had fewer children. But in recent decades this has changed; US families in the top 25% of the income distribution have spent drastically more on childcare since 1990 as their ability to outsource childcare and household labor has grown.1

Now, instead of a linear relationship, high-income countries have begun to exhibit a U-shaped convexity in fertility across the income distribution, with the lowest fertility rates in the middle of the distribution.2

At the most basic (and even intuitive) level, there’s a quantity-quality tradeoff for parents3 — those facing resource constraints must choose between number of children and investment per child. But at the extremes, the pattern differs markedly. The socioeconomic elite can offset the cost of additional children by raising total investment in offspring human capital — their fertility becomes less constrained by marginal costs of additional childrearing. This explains the right (high-income) side of the U-shape.

Yet the left (low-income) side also exhibits high rates of fertility — not because of the cost-benefit calculus, but because lower-income households systematically invest less per child on average. Indeed, lower-income households’ fertility decisions are far less cost-sensitive. And to the extent household incomes are explained by parents’ education levels — they largely are — the National Library of Medicine’s insight is vitally salient: “less-educated women have lower wages, but wages have little of the negative effect on fertility predicted by economic theories of opportunity cost.”

Meanwhile, for middle-income households, having 1-2 kids allows them to invest proportionately large amounts in each child’s development, allowing for adequate devotion to their children’s health, education, and cognitive outcomes. But these households occupy an intermediate zone where they often have sufficient education and income to be acutely aware of costs but insufficient resources to comfortably manage them.

Unlike for poorer, less-educated households (who have children despite financial constraints) or wealthier households (who can afford investment in more children), child-related costs have their largest fertility impact on middle-income households — those most likely to respond to marginal cost changes given their deliberate planning orientation and active fertility control.

This gradient in fertility responsiveness to cost has important implications for policy design; the policy question then centers around identifying which costs constitute major “child-related costs”. Compared to, say, healthcare or education costs, Couillard (2025) found that fully 51% of the total fertility rate decline between the 2000s and 2010s is attributable to housing costs. The effect, according to the paper, is substantial on both timing and quantity; delayed births at high ages reduce completed fertility. One of the author’s conclusions was that housing affordability is likely the dominant policy lever for fertility.4

So, what we often call a “cultural” fertility decline seems to actually be endogenous to housing. Anecdotally, the fact that housing restricts family sizes is commonplace. It is ubiquitous among middle class circles to hear that people would like to have another child, but that they cannot afford “big enough” housing in a “good enough” neighborhood. It is here in this hypothetical, all-too-common family — whose primary binding constraint on fertility is the cost/availability of housing — that the marginal subsidy dollar would almost certaintly provide the largest upward lift on fertility rates. To the extent policymakers are convinced that declining fertility rates in the US constitute a crisis worth addressing, it is abundantly clear that the marginal policy dollar should go towards alleviating the housing costs of middle-income, college-educated5 households.

Claim 2: Investing in young families yields the highest ROI to society.

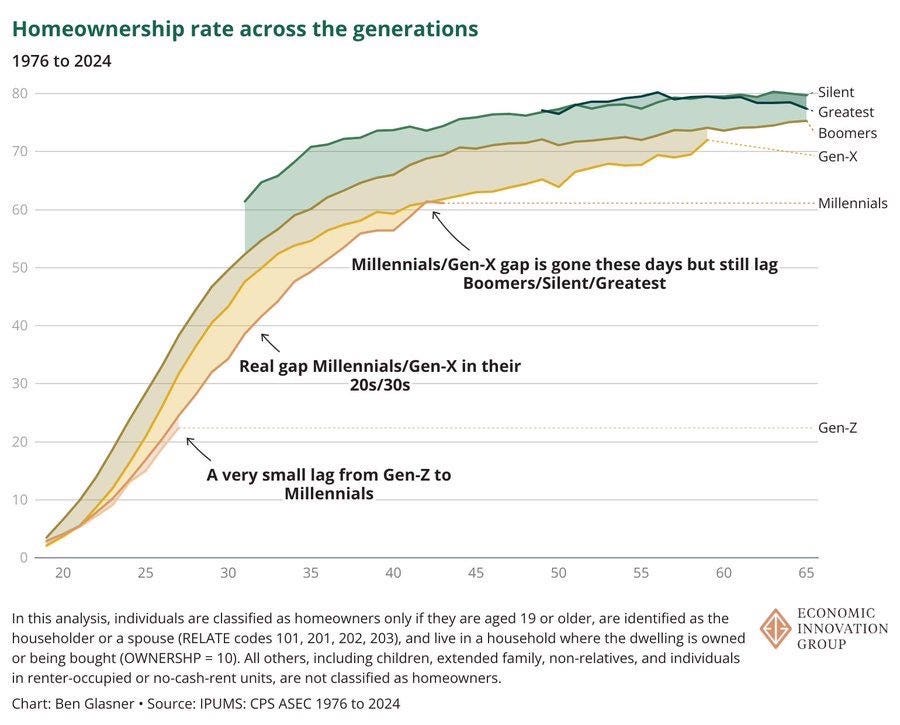

It would be easy to argue that the marginal subsidy dollar should flow to young Americans purely on the basis of need; we have already catalogued the mounting challenges they face across a litany of housing-related adulthood-developmental milestones. They are woefully lagging predecessor generations, it seems.

However, the instinctive logic — X is struggling → state should subsidize X— is a red herring. Struggle alone does not imply optimality for public investment; the relevant criterion for policy is not pity. It is also actually quite debatable whether pity for young Americans is even warranted: their (inflation-adjusted) wealth is above-trend versus previous generations’, ditto for real median hourly wages, and Bloomberg’s viral first-time homebuyer chart was highly suspect.

But when you look at the effects of government transfers to Youngs through an ROI lens, the outsize returns on public capital are immediately obvious. Decades of longitudinal research — from Chetty’s mobility datasets to demographic-fiscal modeling in OECD countries — converge on the empirical reality that public resources targeted earlier in the household-formation arc compound more aggressively than resources deployed later in life. Since Youngs sit at the hinge point of the human capital life-cycle, their decisions about where to live, whether to form families, and how much to invest in skills have a massive impact on the wealth they accrue.6

This early start to wealth accumulation does not just affect retirement wealth but also plays an important role in family outcomes. Daysal et al. (2025) provides some of the clearest evidence of this. Exploiting plausible exogenous variation, the paper shows that housing-wealth gains accruing to parents when children are 0–11 are causally transmitted at rates of 15–27% into the child’s adult wealth, while gains during the teen years have no measurable effect. What is even more interesting is that 60-80% of this wealth transmission operates through mechanisms beyond direct cash transfers — education, earnings, and household environmental effects from improved parental financial stability that all reshape children’s life trajectories.

Barr et al. (2022) also found that with respect to policies targeting families, cash transfers following the birth of a first child increase young adult earnings by 1-2%, with effects large enough that “the longer-term effects on child earnings alone are large enough that the transfer pays for itself through subsequent increases in federal income tax revenue.”7 Thus, what is fundamentally being described here is the positive long run fiscal multipliers associated with families forming households. This logic also reinforces optimal timing.

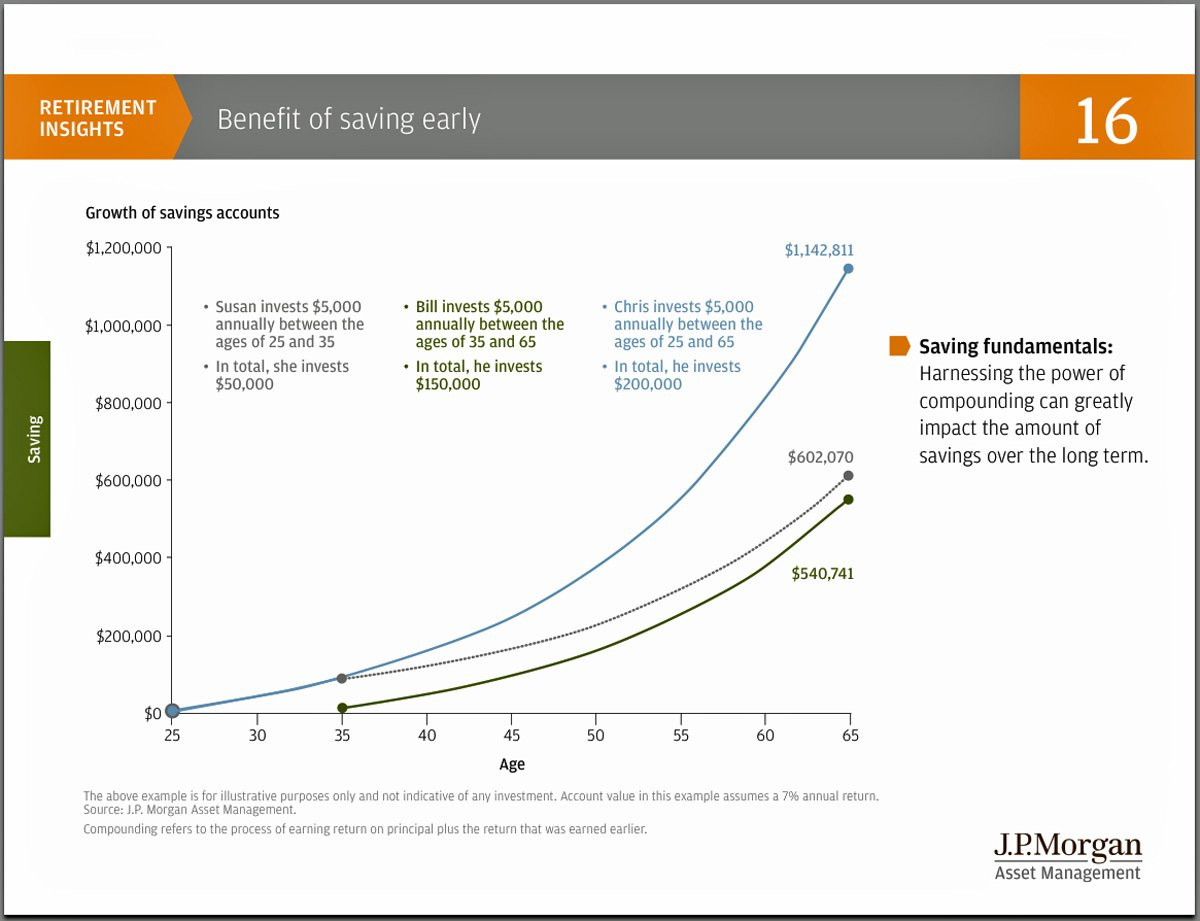

If a family is afforded the ability to save and accumulate wealth early, then they can rely more on the effects of compound interest and, as a result, less on state assistance in paying it back to society. Central to a person’s saving strategy in America — and a key driver of upward mobility for the middle class — is homeownership, or in other words, the “forced savings plan”. Even moderate delays in when a person is able to invest in their first home is a crucial determinant of terminal net worth, as only once homeownership begins does compounding accelerate. Bai et al. (2025) found that “delaying home purchase is shown to substantially diminish the benefits in terms of both wealth accumulation and welfare enhancement.”

Building this home equity not only creates wealth but provides accessible liquidity for emergencies and major life transitions, including the decision to have a second or third child — decisions that for middle-income households remain profoundly contingent on financial security. This is where today’s young Americans are truly lagging previous generations.

What all of this shows is that young people — specifically young families — are uniquely suited for the marginal housing policy dollar: not only does the rest of society reap long-term tax gains from maximizing the income and wealth-accumulation outcomes of young families, but we also noticeably improve the trajectory of their children’s outcomes and the tax base that they will eventually comprise. Indeed, this is where demographic dividends yield the most.

Claim 3: The positive externalities from agglomeration are highest when young, middle-earning human capital are the source of density.

The case for housing policy serving the middle-income cohort extends beyond fertility matters and encompasses the efficient spatial allocation of human capital. Young people, even those in the pre-family formation life stage (but especially young families), represent the social and economic heartbeat of a city.

Urban economists have established that agglomeration effects are not uniform across all types of workers or density configurations. Abel et al. (2010) used comprehensive data from 363 US metros and demonstrated that a doubling of density increases productivity by 2-4% per person on average. Critically, this effect is dramatically amplified by human capital concentration: finance, arts & entertainment, professional services, and information — knowledge-intensive industries — are the ones that exhibit the strongest agglomeration effects, with elasticities reaching 8.3% productivity gains per density doubling.8

Middle-income professionals represent the sweet spot for these inclusive agglomeration effects because they overwhelmingly occupy knowledge-intensive jobs. Young adults relocating “closer to work” in proximity to central business districts triggers cascading economic effects — increasing labor market efficiency positioning everyone to capitalize on job-matching and knowledge-spillover benefits that concentrate in urban cores. Moreover, the Youngs’ spending — on furniture, services, entertainment, local retail, etc. — generates immediate multiplier effects for businesses operating in those neighborhoods.9

Research using GitHub data to track knowledge worker clustering also shows that proximity effects on worker productivity “rapidly decay with distance,” but the decay is much slower — and the initial effects much larger — when the cluster includes diverse mid-career professionals who serve as knowledge bridges across domains.

But this is also an important corollary to household family formation. Specifically for young people, the first step towards family formation is moving out of their parents’ house. This transition is the mechanism behind housing stock turnover and filtering. When young adults form new households chasing higher income opportunities, they vacate family homes or free up rental units in suburban or exurban locations, creating availability that cascades through the housing chain. The filtering process — whereby older market-rate housing becomes more affordable as new units are added — depends critically on this turnover and mobility.

This is precisely where YIMBYs hit the nail on the head: what they call the “missing middle” — moderate-density typologies like duplexes, four-plexes and cottage courts once common in American cities — is analogous to what’s missing in cities with respect to the income distribution, specifically for households with families. (And yes, the missing middle typology goes hand-in-hand with the missing-middle-income family.)

Middle-income families serve as the critical bridging social capital in communities. They possess resources to volunteer, participate in schools, and engage civically, yet remain connected to working-class and lower-income neighbors in ways the wealthy often are not. The mechanism operates through economic connectedness — cross-class interaction that functions as a ladder for mobility — and the economic multiplier is measurable: for each new dollar spent on child care costs, the total statewide economic impact is approximately two dollars, reflecting both direct spending and community engagement effects.10

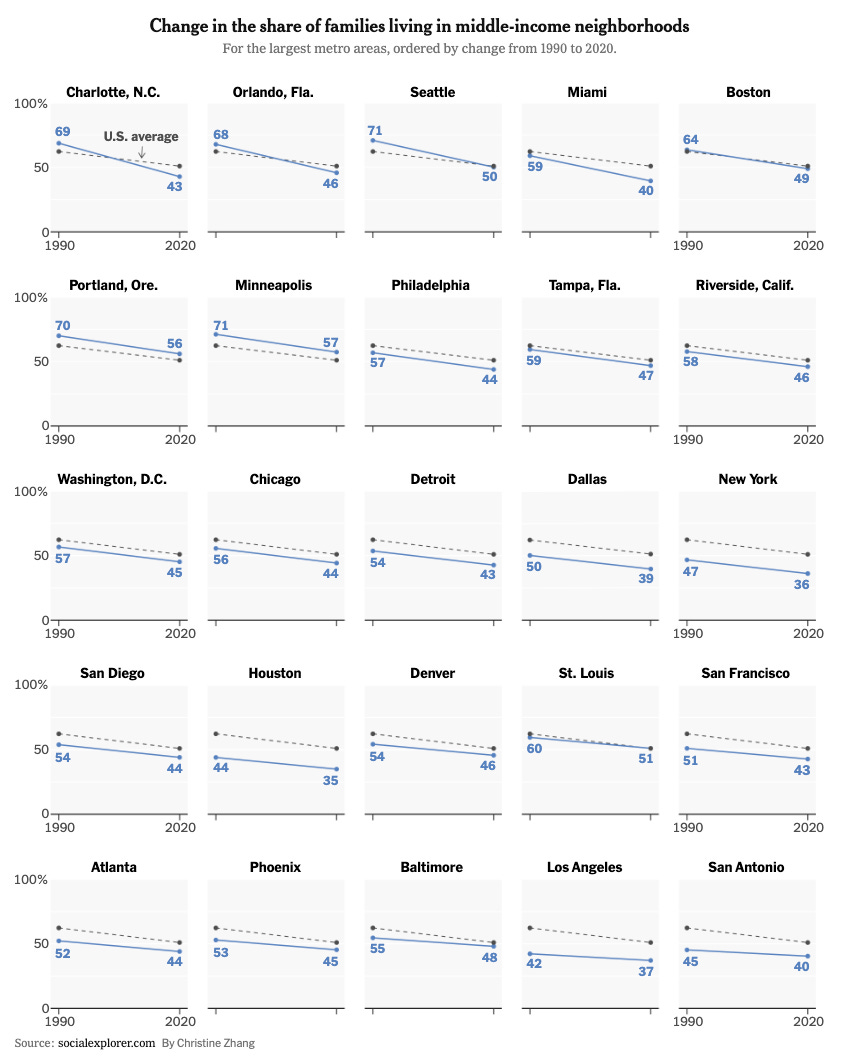

Beyond individual productivity and mobility, middle-income families provide essential community stability and economic resilience. Yet nationally, only half of American families living in metropolitan areas can say that their neighborhood income level is within 25 percent of the regional median. A generation ago, 62 percent of families lived in these middle-income neighborhoods.

So what does this all mean?

First, we know that you don’t get affordable family-friendly typologies without densifying the urban cores first (the sequencing matters), as building more studios and one-bedroom apartments lowers price pressure all the way down the housing stack. But when demand shocks — i.e., many young people moving to urban cores — are not met with adequate supply response, the filtering chain reverses, with older (and more spacious) housing stock becoming more expensive instead of less. This displaces families and incumbents.

Second, when labor pooling occurs, workers have the opportunity to put down roots, purchase homes, start families, and generate tax revenue and social capital that compounds over time. But the composition of supply matters enormously here, as family formation correlates strongly with access to family-sized units — specifically, 3+ bedroom apartments and townhomes that provide adequate space for multiple children.

Finally, institutional capital plays a crucial role in enabling young, educated human capital to agglomerate and yield positive externalities in urban cores. When allowed by local policymakers to participate in the market, institutional developers and investors lower the cost of capital for new multifamily construction and ensure that units at the top of the rental stock are continuously replenished. This, then, serves as a release valve for filtering to free up housing opportunities for upwardly- and spatially-mobile Youngs. Furthermore, in the single-family rental market, given that institutional ownership portends lower rents, institutional landlords serve as an important conduit for middle-class families to concentrate in neighborhoods with high-quality schools and other resources which they would otherwise be unable to afford.

In the next part of this series, we will be discussing existing housing policy regimes — at the federal, state, and local levels — that are delivering persistently suboptimal outcomes for young middle-class families.

Low fertility among high earners has been classically explained by the increasing opportunity costs to having children — as incomes rise, the tradeoff between maintaining high income and childrearing becomes less favorable, fertility-wise. But research shows that as inequality has grown, people with higher incomes can now afford to hire low-wage workers to help them care for their children. Higher-income women can outsource childcare to enable both childbearing and continued labor force participation, effectively relaxing their time constraints.

Recent research across developed countries documents that this fertility convexity occurs once societies surpass a Human Development Index threshold of approximately 0.86 — roughly corresponding to $80-$100k in annual household income in the US.

Becker’s foundational quantity-quality theory of fertility predicts that as income rises, the income elasticity for child quality (spending per child) should be high, while the elasticity for quantity (number of children) should be low. This generates a U-shaped relationship: middle-income families experiencing the strongest substitution effect from quality competition with quantity, while the wealthy can expand both dimensions.

This is corroborated by additional research: across the developed world, the number of children that women actually have is well below the number they say they would like to have. According to one study, after controlling for other factors, a 10% rise in house prices was associated with a 1.3% fall in overall births.

College-educated parents spend dramatically more time with children than less-educated parents — more than 4 hours per week additional for college-educated mothers — and this holds across 13 countries despite higher opportunity costs. Parental involvement translates directly to outcomes: higher engagement is associated with increased probability of high school graduation, college enrollment, and completion.

Moreover, the fiscal externality of a native newborn child ranges from $92k in net present value for children of parents with less than high school education to $245k NPV for children of parents with greater than high school education — a nearly threefold differential reflecting lifetime tax contributions minus lifetime public benefits consumed.

Another study found that the lifetime net tax contribution of an average child born to educated parents is approximately $606k in present value, generating a 700% return on government investment when accounting for fertility support costs.

Part of the reason that it is able to pay for itself is that time horizons matter immensely. If for example a person in their late 50s could have their income increased by 1-2% it would be able to “generate a return” for only the decade or so the person continued to work. By contrast these investments not only increased the family which received the transfer but also increased their children’s outcomes leading to an effect which persists for 5-6 times as long. In general, small changes to trajectories early in a person’s life can have enormous effects on terminal outcomes which even large interventions later cannot overcome.

The mechanism operates through liquidity at critical life-course junctures. Young families forming households face acute capital constraints precisely when investment returns — both in children and in housing equity — are highest.

Metropolitan areas with human capital stock one standard deviation below the mean realize essentially no productivity gain from density, while those one standard deviation above the mean see productivity benefits roughly twice the average.

Not to mention that it reduces commute times, and makes cities more climate-friendly.

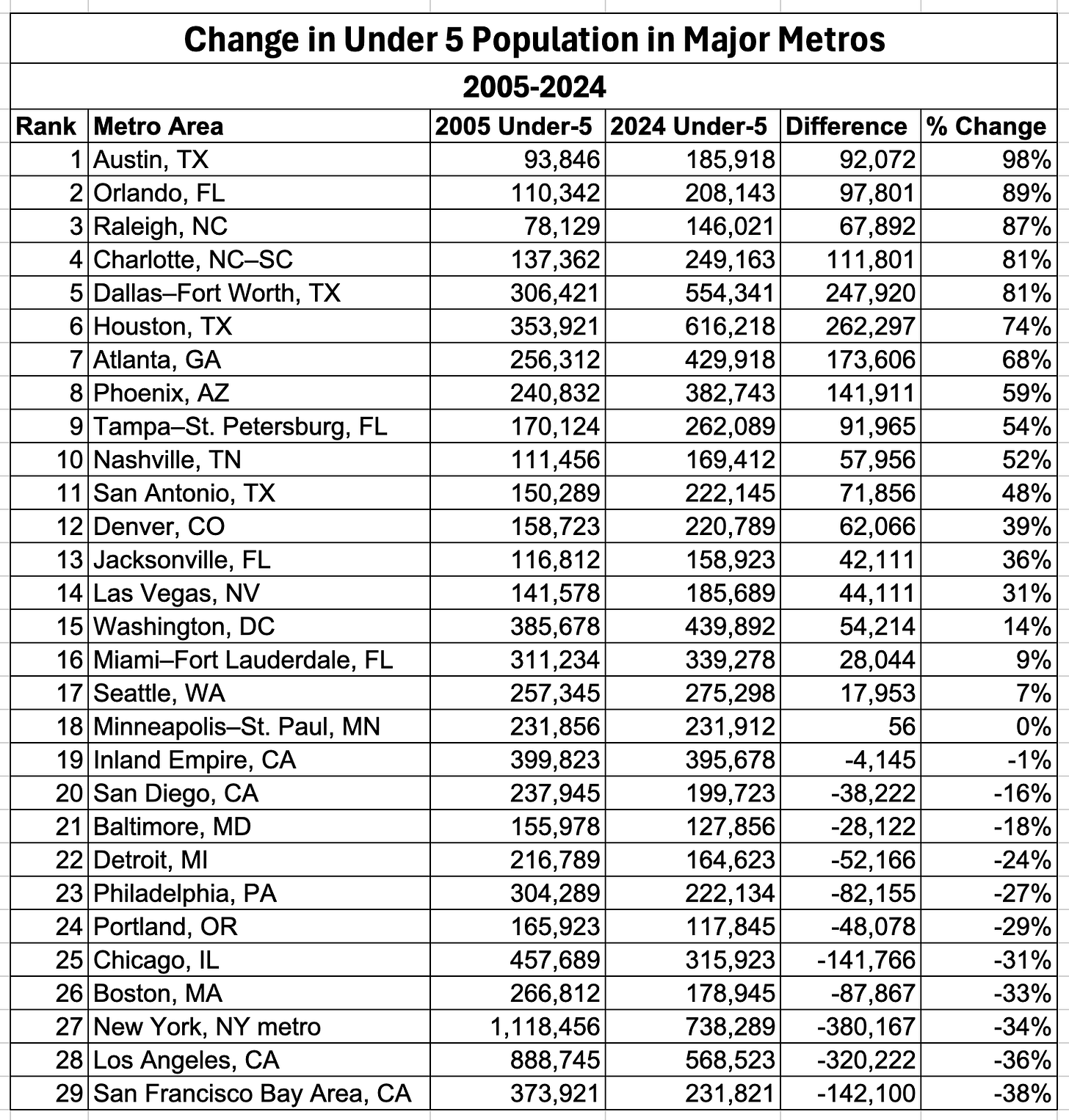

Tragically, some of the most dense US cities are the ones that are no longer home to young children (source: Bobby Fijan on X):