Which Pill, Housing Crisis Observer?

The competing narratives, steel-manned

Preamble

Now a month into our sprint on the ongoing housing crisis, our eyes are starting to look downfield. We spent the better part of September in discovery mode but will be transitioning, from the de-scriptive to the pre-scriptive over the course of October, with the plan to spend much of November highlighting bold, asymmetric ideas. (Submit yours via our essay contest!)

This essay is an attempt to highlight and map the lenses through which the true causes of the housing affordability crisis may be assessed. Think of the “pills” — à la Morpheus — as stylized schools of thought, each steel-manned with evidence and our best understanding of the internal logic.

The Glaeser (supply), Mamdani (market power/financialization), Fed (monetary plumbing), Immigrant (demand composition), Ghetto (amenities/order), Boomer (generational balance-sheet effects), and Bubble & Bust (cycle dynamics) Pills aren’t mutually exclusive; housing is one of the most complex and multi-faceted topics, politically and economically speaking. But together we hope these competing narratives form a matrix for diagnosing where constraints truly bind — and which levers have the potential to actually move the needle in the right direction.

We at Boyd have our priors, but we’ll present each case as its proponents would. Missed an angle? Tell us in the comments👇

Mamdani Pill

The Mamdani Pill represents the trust-busting, “eat the rent” approach to housing — one that’s fundamentally rooted in criticisms of free market pathologies (and, more spicily-said, the fetishization of the “petit-bourgeoisie,” or “mom and pop”).

According to this school of thought, chronic unaffordability is less a story of abstract supply and more a product of market power and financialization (Dancygier & Wiedemann 2024), up and down the stack. That is, the argument that major market participants — data providers like Zillow and Redfin; private equity/asset management firms like BlackRock Blackstone and Greystar; REITs and other institutional landlords; national homebuilders like D.R. Horton and Lennar — are in cahoots, synchronously engineering (or, at least, maintaining) scarcity.

Furthermore the argument goes that “they” — private market actors — facilitate this engineered scarcity via unique access to cheap capital, the leveraging of algorithmic price-setting and data advantages, paced building, and coercive eviction policies, among other methods, to extract rents at the expense of a community’s basic needs.1

Adherents to this pill are ambitious in the egalitarian sense; they put a very high value on “economic freedom,” tying it directly to the threat of monopolies and maintain that concentrated corporate power erodes liberty and democratic institutions. They view housing’s transformation from shelter into a yield-bearing financial asset as both symptom and cause of this broader democratic decay.

Intellectually, it’s rooted in Brandeisian political economy: Louis Brandeis’s Other People’s Money and The Curse of Bigness argued that a corporation “may well be too large to be the most efficient instrument of production and distribution” and “may be too large to be tolerated among the people who desire to be free”. The modern, neo-Brandeis project — e.g., the New Antitrust Movement with its “stable of elected officials like Sen. Elizabeth Warren, and a set of semi-celebrity bureaucrats including Jonathan Kanter, Tim Wu, and Lina Khan” — runs on the contours of this analysis.

That Blackstone owns 230,000 apartment units and private equity controls entire neighborhoods, or that Lennar’s gross margins nearly eclipsed 30% during the post-Covid housing boom, is evidence, they say, that “housing policy is actually corporate policy” — and that a crisis in housing affordability is just the predictable outcome of consolidated market share layered atop financialization. Corroborating these arguments is a sort of economic folklore, which asserts that America’s housing affordability crisis is orthogonal to regulatory-induced supply-side constraints. But it isn’t entirely devoid of empirical support, either (see: Cosman & Quintero 2022 and Kohl 2021).

The political manifestation of this is situated somewhere between mere democratic populism and, more recently, outright socialism. The pill’s more Marxist-leaning variant — encapsulated in NYC mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani’s platform — takes antitrust considerations a step further; it’s taking aim, center-mass, at private ownership altogether. Mamdani’s proposals for 200,000 units of social housing, four-year rent freezes, and state-owned grocery stores represent what he calls a movement “toward the full de-commodification of housing”.

Then there is also the demand side of things, which, per Stephen Kirchner in a recent piece,

“is increasingly being socialised through increased rental assistance, assistance to first home buyers, and government lending guarantees in an effort to mitigate the impact of the underlying shortfall in new housing construction relative to demand. It is a dynamic that the Niskanen Center has labelled cost-disease socialism.”

This reflects the Mamdani Pill’s core thesis: treating housing as commodity rather than human right inevitably produces artificial scarcity and speculation that no amount of supply-side tinkering can plausibly resolve.

Glaeser Pill

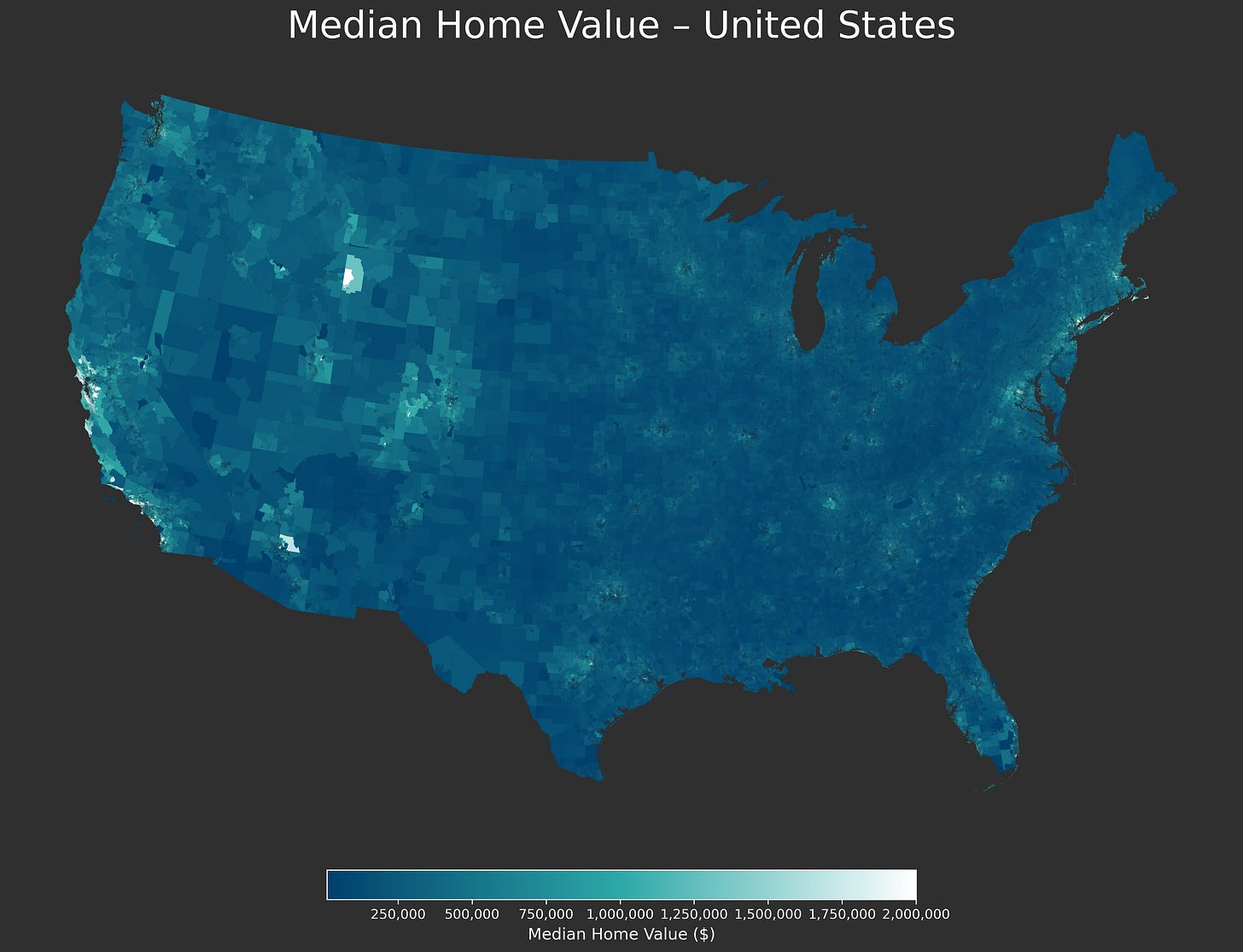

In stark contrast to the “folk economics of housing” (Elmendorf, Nall, & Oklobdzija 2025), Glaeser Pill subscribers treat the affordability crisis in housing as a supply-elasticity failure — “prices are high, but supply is effectively unresponsive to increases in housing demand.” Because of this artificially flattened supply curve, the argument goes, we don’t permit and deliver enough homes in “superstar cities” (i.e., America’s largest, most productive urban regions where people most value living).

In plain economics: when the supply curve is kinked by policy, price must clear the market. The mechanism is the familiar price-to-cost wedge, where binding local rules — exclusionary zoning, height caps, parking minimums, discretionary approvals, environmental/process litigation — keep feasible housing quantity below demand, so prices float above marginal construction cost. That wedge metastasizes into spatial misallocation, where high-productivity human capital is priced out of high-productivity metros, leaving potential output on the table.

In application, the Glaeser Pill — named after the prominent Harvard economist Edward Glaeser, who first articulated the gap between price and production cost as a “regulatory tax” (Glaeser & Gyourko 2018) — is tantamount to a Homevoter Hypothesis-esque public-choice critique (Fischel 2001). That is the view that politics, not economics, constitutes the primary obstruction.

The thesis runs as follows: homeowners are rational “homevoters” whose undiversified wealth sits in their property, so they vote to protect (and ideally increase) its value. This extends to local governments not only using zoning to regulate land use, but deploying “fiscal zoning” (Hamilton 1975) to manage their tax base — prioritizing land uses that generate high property tax revenue with low service costs (e.g., large-lot single-family homes, commercial properties), while restricting housing types that may bring in lower tax revenue or higher public expenditures (e.g., multi-family units that bring children needing schools, or affordable housing that increases demand for social services).

The result is a political cartel of scarcity that transforms housing from a competitive market into rentier extraction.

Folded into the Glaeser Pill framework is the YIMBY/Abundance movement — call it supply-side progressivism but with technocratic characteristics. It’s not deregulation-as-dogma, per se, but targeted deregulation paired with enhanced state capacity. The YIMBY instinct — “legalize housing” — merges with the Abundance agenda’s goal of industrializing the delivery of new housing supply at scale: ministerial approval processes and permit shot-clocks to kill timeline risk; standardized plans and code simplification to reduce soft costs; manufactured/modular to compress construction cycles; transparent fee schedules and by-right ADUs/missing-middle typologies so small builders and infill developers can actually compete against established players.

Glaeser Pill adherents see themselves as championing the individual right to build against the community right to exclude, yet they are willing to deploy state power strategically. Most in this camp would concede that targeted aid is still needed for the bottom quintile, but the central claim stands: without throughput, price becomes policy.

Fed Pill

Money printer go: 2020-2022, “brrr”; 2022-current, “fuck your dreams of homeownership”

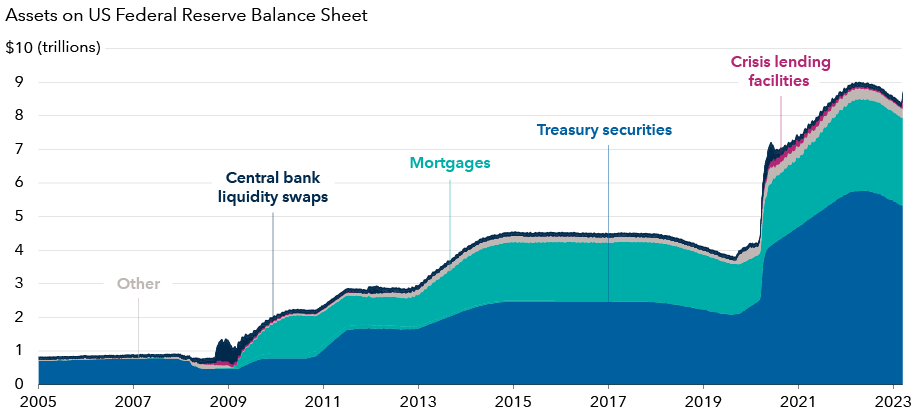

This pill argues that Fed actions have been the primary driver of the housing crisis. It views chronic housing unaffordability as the outcome of monetary policy run amok — that it acutely distorted housing markets beyond recognition. The Fed’s post-GFC (and then again, post-Covid) large-scale purchase programs of assets like mortgage-backed securities (MBS), in other words, didn’t just inflate asset bubbles — they fundamentally broke the housing market’s price discovery mechanism, creating perverse incentives that persist even as monetary policy has ostensibly “normalized.”

Those who are Fed Pilled, seemingly inherently wary of policymakers and technocrats, synthesize their critique with empirical research on monetary transmission mechanisms: when a central bank simultaneously holds rates below their natural level (ZIRP), executes trillions upon trillions in open market Treasury and MBS purchases (QE), and floods its overnight reverse repo program to the high watermark tune of ~$2.6 trillion, it disproportionately benefits incumbent owners and refinancers while making overall housing attainability for the median buyer little improved (if at all).

Rather, they argue that in practice, cheap, debased money has transformed housing from shelter into speculative store of value, encouraging leverage and financialization while marginalizing savers and first-time buyers.

The timeline does appear damning. Benchmark 30-year mortgage rates plummeted from around 5 percent in 2010 to historic lows below 3 percent during the pandemic, fueling a speculative frenzy that saw home prices appreciate 40 percent nationally between 2020 and 2022. But the Fed’s subsequent quantitative (and otherwise) tightening — ushering in a rapid increase in mortgage rates, which have hovered in the 6-7% range since 2022 — created an even more pernicious dynamic: the mortgage lock-in effect where existing homeowners with sub-3 percent mortgages are rate-caged, unwilling to sell and lose their below-market financing.

This artificial gridlock, or reduction in housing turnover — this “golden handcuff” of low mortgage rates — has throttled inventory and kept prices elevated, causing affordability to plummet.

In a September 2025 speech, Fed Chair Michelle Bowman expressed concern about a potential “sharp housing market correction” as rates normalize, noting that accelerating declines in home prices could pose a “downside risk to housing wealth.”2 Fed Pill adherents see this as an admission of guilt — that the post-Bernanke Fed’s perseverative concern with the wealth effect (Bernanke 2017) as a driver of aggregate demand stands as the primary culprit in the ongoing housing crisis, not prohibitive zoning/regulations or corporate rent seeking.

Immigrant Pill

Over the last 30-odd years the United States has experienced an unprecedented wave of migration from across the entire world. In 2025 over 50 million people, or more than 15% of the U.S. population, were not born in this country. Since housing, like all goods, is fundamentally a function of supply and demand (contra-Mamdani Pill), the inclusion of so many people cannot be easily ignored.

Not only this, but the foreign-born population in this country is not homogeneously spread out. In a place like NYC or San Francisco—both among the most unaffordable cities in America—the fraction can reach nearly 40%. Since immigrants are by definition relocating to the U.S., they naturally tend to select into the most economically dynamic places – the “superstar metros”. If moving to another country, where would you choose to move?

This, combined with the fact that many of those same cities are defined by housing markets with very little supply elasticity (Glaeser and Gyourko 2025), means the additional demand pressure on the housing market pushes up prices. This fact has been documented by a number of academic papers (Saiz 2007 & Mussa et al. 2017) and passes an intuitive smell test. If a market has high supply elasticity—or in short, if it is able to build new housing in response to high prices—the story, of course, becomes more complex.

But it is worth reiterating that much of the U.S. is defined by a nearly static supply of housing, including and especially those two previously mentioned cities.

New arrivals also change the communities they live in. This can have limiting effects on the availability of housing for natives both in cases where immigrants have superior socio-economic outcomes and where they do not. In other words, immigrants can have positive income effects on a community and as a result drive up prices, or they can have negative income effects on a community and in turn accelerate native out-migration.

People also have a strong preference for living near their own ethnic group (Clark 1991 and Schelling 1971). That means diversity has a shadow cost on housing which does not exist in a homogeneous society. If you want to live in a community that is majority Thai, for example, the degree to which that would restrict your neighborhood option set would depend explicitly on what fraction of the population was Thai.

Fundamentally the immigrant pill believes that America’s increasing ethnic diversity coupled with a tendency for ethnic localization is forcing natives to live in a smaller and smaller set of communities – and also imposes undue demand pressure on the “superstar metros”.

Ghetto Pill

When examining U.S. housing affordability, one cannot ignore the phenomenon of urban dysfunction. In places like Detroit, poverty, crime, and abandonment reach staggering rates. This dysfunction is clearest in the Midwest, where the traditional urban cores have collapsed while their exurbs and suburban rings are some of the most expensive in the country.

Detroit, St. Louis, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and others were once among the wealthiest cities in the world, but with the hollowing out of the manufacturing sector and subsequent explosion of crime in the middle of the 20th century this changed. Between 1950 and 2020 Detroit lost nearly 70% of its residents and fell from the 5th to the 27th largest U.S. city. In 2012, a third of its land—40 square miles—was vacant. St. Louis, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh each lost around half their populations, and even Chicago is down by a third. Vacancy in some neighborhoods exceeds 20–30%, compared to a 1.6% national average.

This dysfunction drives people who can afford to leave out. In addition to encouraging out-migration, disorder also causes communities to put up barriers to new development for fear of filtering in the “wrong type of person.” In a survey of developers in New York state, for example, crime was by far the most often listed concern. Since the dynamics of urban dysfunction interact with the very culturally sensitive topic of race, people tend to prefer not to talk about it at all.

As a result, Ghetto Pill adherents believe that the housing affordability debate often ignores that there are communities in almost every city with low housing costs, but that people choose not to relocate to them for good reason. Low home prices in ghettos, and high prices in the suburbs, simply reflect an arms race between families to escape poverty and dysfunction.

Boomer Pill

One of the most underappreciated drivers of today’s housing crunch is generational. The Baby Boomers are now in their 60s, 70s, and early 80s and control the plurality of housing wealth – over 40% of all real estate assets. Many of these homes were purchased decades ago at prices that seem almost fantastically low, even in inflation-adjusted terms.

As a result, Boomers dominate demand – and supply – in the housing market today. Because they bought early and were often able to refinance with very low rates during ZIRP, many are able to use accumulated equity to outbid younger buyers. From July 2023 to June 2024 Boomers comprised 42% of all home purchases compared to only 29% for people between the ages of 26 and 44 . This is a radical departure from the late 20th century, for example in 1981, when the median age of a person buying a house was just 31 years old.

In addition to dominating demand in the market due to their accumulated home wealth and access to lines of liquidity, a staggering 40.3% of U.S. owner-occupied housing units are now mortgage-free — the overwhelming majority of which is comprised of Boomer (or geriatric-adjacent) home equity:

Boomers also tend to occupy the largest homes, leading to a phenomenon of many rooms sitting empty. Census data shows that rates of “under-occupation”—owning three- or four-bedroom homes with only one or two people living in them—have risen sharply in recent years.

Though Boomers may be sometimes vilified, there is, of course, nothing sinister at play here. What is unique is that people are simply living longer, which allows them more time to accumulate wealth and then enjoy it. It does, however, mean that unlike in previous eras—when there were very few elderly to compete with the young for scarce resources—this is no longer true. The Boomer Pill believes that this dynamic, although the result of something unequivocally good (e.g., everyone living longer), has had distortionary effects on the ability of new families to break into the middle class through homeownership.

Bubble & Bust Pill

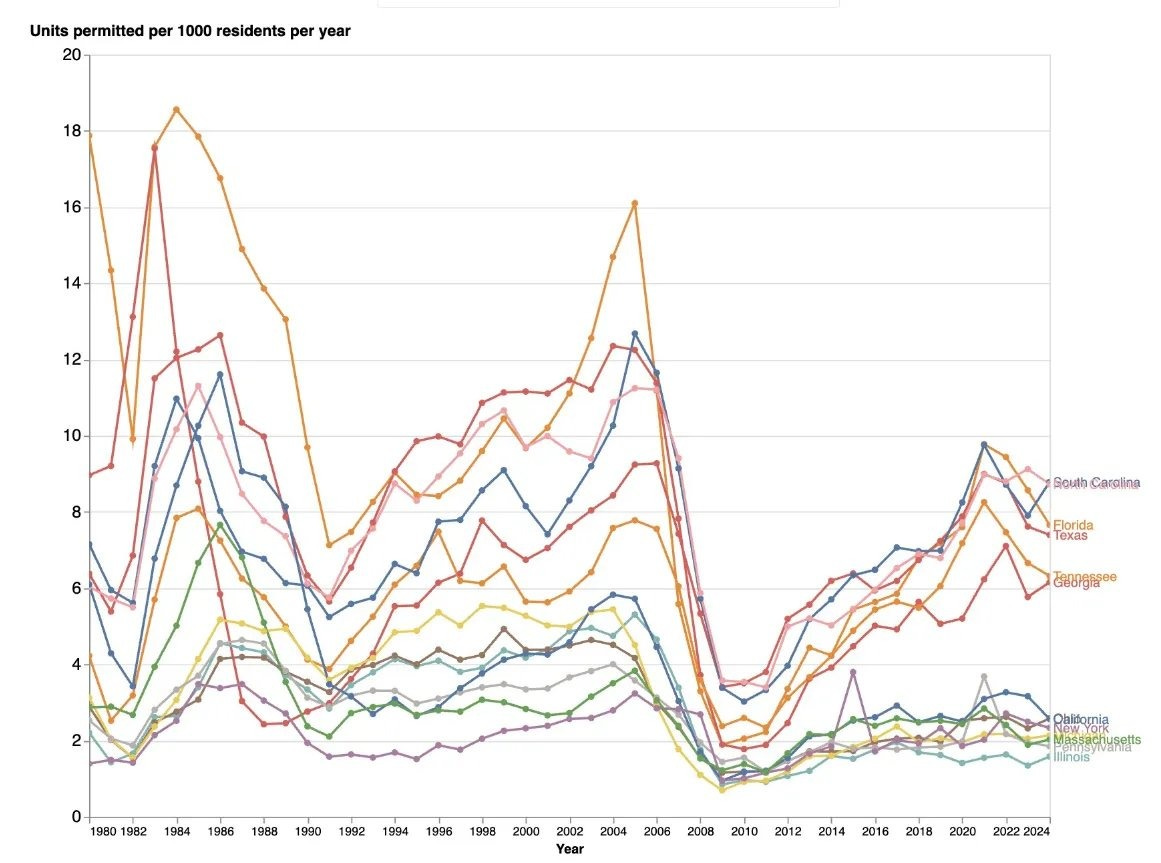

When examining the history of housing construction in the U.S., a clear cyclical boom-and-bust pattern emerges. The most recent and dramatic example came with the 2008 financial crisis, when builders pulled back sharply and new housing construction fell to some of the lowest levels on record.

This collapse in construction did not mean a collapse in population growth. To the contrary, household formation and demographic expansion both continued apace. Over time, the mismatch created a cumulative housing supply deficit that steadily put upward pressure on prices. In fact, much of today’s affordability crisis in housing can be traced back to that decade-long stint of underbuilding.

By the mid-2010s, prices were already climbing well above historical norms, and during 2020–2022 the combination of record-low interest rates and exorbitant investor demand dramatically accelerated the surge. With cheap capital pouring in and households searching desperately for space, especially during the pandemic, markets quickly overheated.

Developers responded. By the early 2020s, construction had not only recovered but, in certain regions—particularly the Sunbelt—entered into a new boom cycle. Entire subdivisions and apartment complexes were thrown up, and in some metros collapsing rents and sale prices are already the visible product of overbuilding.

If you subscribe to the Bubble and Bust Pill, housing affordability is not so much a chronic structural problem as a cyclical one. Just as the long drought of building after 2008 produced shortages and high costs, the surge of building in the 2020s may soon produce the opposite effect – and government policy might soon be directed towards keeping prices afloat. Looking to a world after the Boomers, absent sustained net migration levels, we may have already built too much housing.

The recent federal antitrust case alleging algorithmic rent-setting (DOJ v. RealPage & six major landlords) is, to adherents of this view, the mask slipping: housing prices can be managed from the top down when markets are thin and information is pooled.

Bowman also commented: “I do suggest that if you want to better understand the conundrum of the housing market, read the book Abundance by Ezra Klein to better understand that housing has a long-term future defined by both structurally short supply and not just growing demand, but growing need for housing as well. The current environment is all about recognizing that short supply is keeping prices higher and that only lower prices enabled by lower cost structures will achieve affordability.”

If you simply make it undesirable to live there, prices will decline. I am crime pilled

IMO, certain MSAs will become too cheap to ignore and and population will flow that way.

I look at Detroit, which is now the Mortgage City instead of the Motor City.

Look at the MSAs which are appreciating and which ones aren't. I call it the Hip To Be Square trade.